On August 8 this year, the United States (US) announced the halting of visa processing for Zimbabweans intending to migrate to that country.

Whereas diplomacy thrives on the notion of reciprocity, Zimbabwe did not retaliate but rather demonstrated a willingness to comply with the American visa position.

The stance exhibits Zimbabwe’s foreign policy shift, uncharacteristic of the late President Robert Mugabe era, which was punctuated by confrontational and rhetorical diplomacy.

The current tactful stance of continuing to re-engage the US warrants critical an look into the complexities of such a position, but more importantly, the opportunities that beckon from such a move.

This development comes after a series of new travel policies in June as the Trump administration works to reduce illegal immigration in the US.

Zimbabwe, alongside Malawi and Zambia, has come under fire as citizens of these countries are among the cases of overstays and visa misuse. Now, people wishing to travel to the US for business or tourism have to pay a bond of up to US$15 000.

Zimbabwe has a complicated history with the US, dating back to the fast track land reform programme in the early 2000s.

As a result, the US government enacted economic sanctions citing human rights abuses and breakdown of the rule of law.

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Bulls to charge into Zimbabwe gold stocks

- Ndiraya concerned as goals dry up

- Letters: How solar power is transforming African farms

Keep Reading

More recently, Zimbabwe’s disputed 2023 elections attracted further sanctions against Zimbabwe’s first family and other high-level government officials.

This, in turn, pushed Zimbabwe to deepen relations with Russia and China, superpower rivals to the US.

The visa ban thus presents a tense turn in relations, at least from the US’s side. President Trump’s domestic and foreign policies have an “America First” outlook, which heavily contrasts with erstwhile internationalist policies.

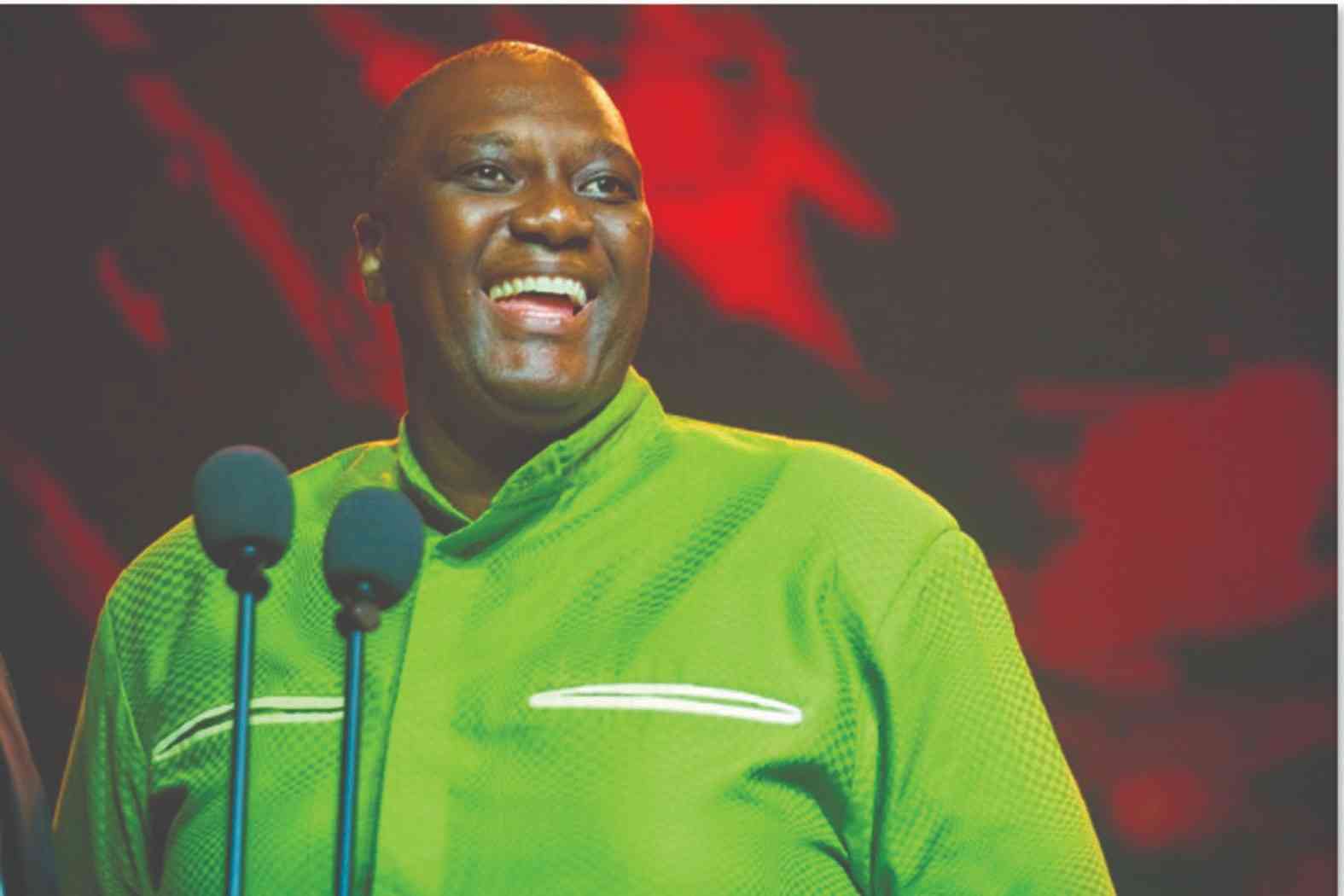

Meanwhile, President Emmerson Mnangagwa has applauded the deportation of Zimbabweans living illegally in the US. His response coincidentally aligns with his popular mantra, “Nyika inovakwa ne vene vayo” — A nation is built by its people. This developmental philosophy speaks to nation building and patriotism, principles some Zimbabweans have failed to resonate with for a while.

For the average Zimbabwean citizen, the US has long been a political, social and economic Canaan, with many relocating to secure better prospects for themselves and their families.

An indefinite restriction presents uncertainty over access to the afore-mentioned opportunities.

For Zimbabweans seeking higher education opportunities abroad, the US offered a wide range of prestigious institutions such as Harvard, Yale and Stanford.

These institutions are successful because the US government funds and supports their research and learning objectives with the understanding that education builds stronger societies.

This has spurred the US’s global pedagogical dominance, which has influenced Zimbabwe’s dependence on the US’s higher learning institutions.

Therefore, the visa ban brings certain challenges to the fore, such as cut-offs from scholarships, fellowships and exchange programmes such as the Fulbright and the MasterCard Foundation, which were of critical importance to many Zimbabweans.

This leaves study-abroad options solely open for upper-class families, therefore widening the inequality gap.

The restrictions on accessing top institutions also affect Zimbabweans’ ability to participate in global innovation initiatives in STEM and artificial intelligence.

For an aspiring doctor or engineer in Mutare or Kwekwe who is looking forward to learning at Yale or the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and ultimately bringing back that knowledge, this is a loss that strains Zimbabwe’s overall development ambitions.

Nevertheless, this ban provides Zimbabwe with a critical turning point in its higher education system if leveraged on wisely.

The government is, therefore, tasked with reviving the education sector through investing in funding, education and employment pathways for Zimbabwean youth.

Some key elements would involve investing in lecturers, reassessing and crafting a curriculum that reflects our Education 5.0 doctrine and making higher education more accessible to rural communities.

Another route would be to introduce educational exchange programmes intra-continentally.

For instance, the Rwanda-Zimbabwe teacher recruitment programme could be extended to students studying various disciplines on the continent.

Students with an interest in nuclear engineering could enter into exchange programmes and seek scholarships with countries working on nuclear programmes such as Ghana and Niger, while those with an interest in marine biology could further their education or research in maritime nations such as Tanzania or Madagascar.

Even further, Africa as a tourism hub is an opportunity for students from Zimbabwe to partake in hospitality work and study programmes that promote financial independence and cultural exchanges.

The other critical segment to ensuring secure livelihoods for Zimbabweans who would have otherwise migrated to the US is addressing the employment issue.

Historically, Zimbabwe had major industry players in textiles, steel and automotive, such as Zisco, David Whitehead Textiles and Willowvale Motors.

These industries were the backbone of the economy, exporting their products to the Southern African Development Community and the European Union under preferential trade agreements.

The President has made notable efforts to revive industrialisation and economic development through the Manhize steel plant, the Mutapa Investment Fund, the Kwekwe solar power project and the highway dualisation projects.

Nevertheless, the journey to providing employment and entrepreneurship avenues for 49% of the youth population will require commitment and strategic implementation at the policy and grassroots levels.

As the US moves to protect its national interests and reconfigure global relations, countries that have relied on its institutions and platforms for socio-economic prospects will require a major shift.

Nevertheless, these recent changes are an opportunity to strengthen local institutions and invest in youth development.

Zimbabwe and the rest of Africa are at a critical moment, whereby we must take the mantle upon ourselves to initiate and innovate.

We want a Zimbabwe where youth thrive in local education and career spaces.