China has introduced sweeping new internal rules that significantly tighten state control over Catholic clergy, extending the Communist Party’s long-standing exit controls to bishops, priests, deacons, and nuns across the country.

Under the new regulations, Catholic clergy are required to surrender their passports and all other travel documents, with overseas travel permitted only after prior approval and followed by mandatory post-trip reporting.

The measures, adopted on December 16, mark a notable escalation in Beijing’s management of religious personnel and further blur the line between religious administration and political supervision.

The rules were jointly issued by the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CCPA) and the Bishops’ Conference of the Catholic Church in China (BCCCC), both state-controlled bodies operating under the oversight of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

An official document obtained by The Epoch Times, alongside interviews with clergy and church members, indicates that the policy applies nationwide and affects all ranks of Catholic clergy without exception.

Centralised passport seizure

At the core of the new rules is mandatory centralised management of travel documents. Clergy must hand over ordinary passports, Hong Kong–Macau travel permits, and Taiwan travel permits to church authorities for collective safekeeping.

Individuals are no longer allowed to retain their own documents. Any overseas or cross-border travel—whether undertaken for church duties, training, conferences, or personal reasons—requires prior approval from supervising authorities.

Once permission is granted, the travel documents are temporarily released for visa applications. Upon returning to China, clergy must surrender the documents again within seven days and submit written reports confirming their return and detailing their activities while abroad.

Unauthorised itinerary changes, overstays, or failure to return documents are listed as violations subject to disciplinary action.

This system closely mirrors the CCP’s long-established exit controls imposed on government officials, party cadres, and executives of state-owned enterprises, whose passports are routinely confiscated to prevent defections, limit foreign contact, and ensure political compliance.

By extending this framework to Catholic clergy, the authorities appear to be categorising religious personnel as politically sensitive actors rather than purely spiritual figures.

Managing clergy like state officials

For years, passport control has been a central instrument of the CCP’s governance model. Officials and employees in sensitive sectors are required to seek permission for overseas travel, submit detailed itineraries, and report after returning.

Applying this system to Catholic clergy signals a shift in how the state views religious figures: less as leaders of faith communities and more as individuals whose movements and interactions must be closely monitored.

The document’s language reinforces this interpretation. Although issued in the name of church bodies rather than as a formal law, it repeatedly references “approval by supervising authorities,” a phrase commonly found in CCP administrative directives.

The approval mechanisms and disciplinary provisions closely resemble those used in state bureaucracies, highlighting the deep integration of religious administration into China’s broader political control apparatus.

Restrictions on private travel

The rules impose particularly stringent conditions on private travel. Clergy seeking to travel abroad for personal reasons must submit a written application at least 30 days in advance, specifying the purpose of the trip, itinerary, duration, and accompanying individuals.

Applicants must also sign a written pledge agreeing to comply with the approved plan and are prohibited from altering their itinerary or overstaying once overseas.

Such requirements significantly limit spontaneous or informal travel and place religious personnel under continuous scrutiny. Even non-official travel becomes subject to bureaucratic vetting, reinforcing the message that overseas contact—religious or otherwise—is viewed with suspicion.

Discipline and enforcement

The document outlines a range of disciplinary measures for non-compliance.

Violations such as failing to surrender travel documents, travelling without authorisation, changing itineraries without approval, overstaying abroad, or refusing to return documents may result in warnings, suspension of travel privileges, or more serious penalties under state religious regulations and internal church rules.

While the document does not specify criminal sanctions, the reference to “serious discipline” signals that violations could have lasting consequences for a cleric’s status, assignments, or ability to function within the state-recognised church system.

In a context where religious activity is already tightly regulated, such disciplinary powers add another layer of pressure on clergy to conform.

Impact on Catholic life

Catholic clergy interviewed by The Epoch Times described the measures as a sharp departure from long-standing religious practice.

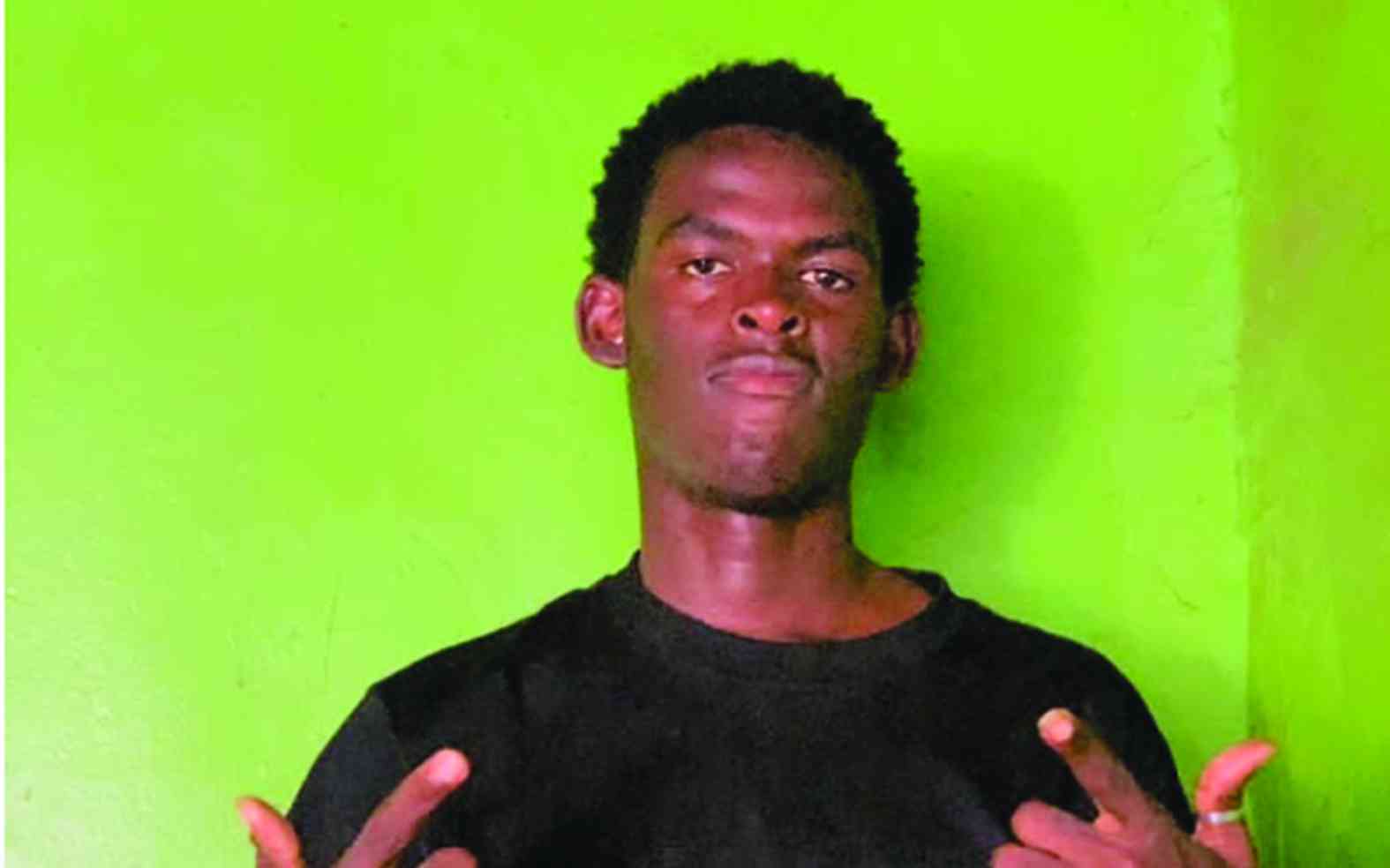

Father Wang, a priest from St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in Shenzhen who requested anonymity beyond his surname due to safety concerns, said international engagement is central to Catholic life.

“Catholicism is a universal religion,” he said. “Overseas conferences, theological training for priests, and participation by nuns in international organisations have always been normal for Catholics. Now we’re required to hand in our passports—it feels like we’re being controlled.”

Such restrictions affect not only the clergy but also the broader Catholic community.

International exchanges, training programmes, and participation in global Catholic organisations have historically been important for theological education and pastoral development.

The new rules make such engagement contingent on political approval, potentially reshaping how Chinese Catholicism interacts with the wider Church.

State-controlled church and the Vatican

The new passport rules must also be viewed against the backdrop of China’s complex relationship with the Vatican.

The CCPA and BCCCC operate under state oversight and allow China’s National Religious Affairs Administration to appoint bishops and moderate church teachings.

Historically, the CCPA functioned outside communion with the Vatican, but recent years have seen efforts by the Holy See to cooperate with Beijing on bishop appointments.

Despite this rapprochement, underground Catholic churches—whose members remain loya