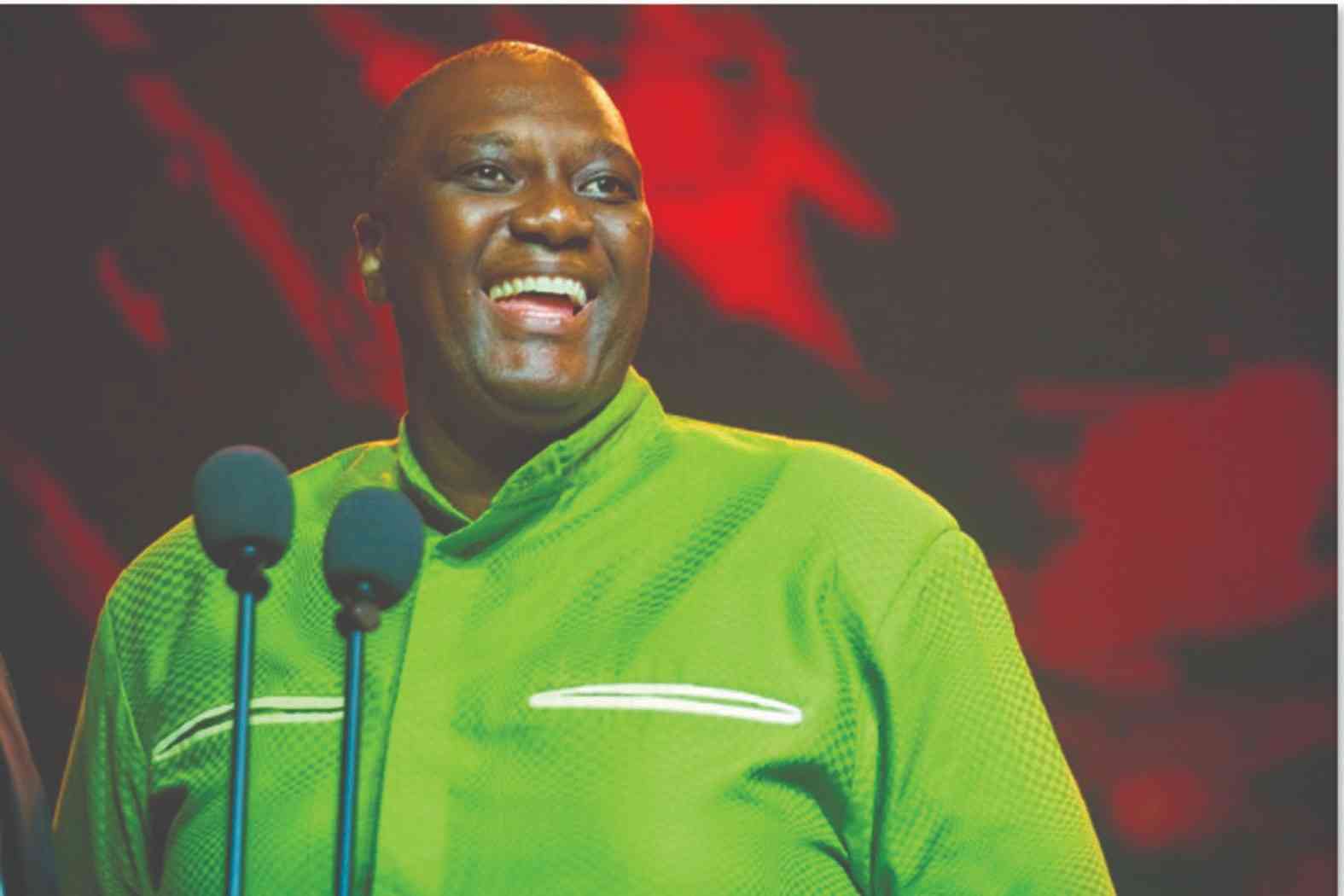

FINANCE, Economic Development and Investment Promotion minister Mthuli Ncube has said the majority of Zimbabweans have entered the upper-middle-income bracket.

The economy is eyeing an upper-middle-income economy status by 2030.

Ncube told a pre-budget seminar in Bulawayo last week that the economy was on course to an upper-middle-income economy status.

“So, the minimum GNI [gross national income] per capita should be US$4 500 per person and this is an annual figure. That means that you ought to be able to spend on any given day no less than US$12 per person.

Currently, with the GNI per capita of US$3 300, that implies that we are spending US$9 per day,” Ncube said.

GNI measures the total income earned by residents of a country, including income earned abroad.

A GNI per capita of US$4 500 signals a better standard of living for citizens.

However, lived realities paint a different picture.

- Drama around Ndebele king making a mockery of the throne

- Commodity price boom buoys GB

- Umkhathi Theatre Works on King Lobengula’s play

- New perspectives: Building capacity of agricultural players in Zim

Keep Reading

Rising inequalities and the widening gap between the haves and have-nots mean that wealth is concentrated in a few hands.

An economy in which people put money under mattresses and large transactions are conducted on a cash basis means that financial institutions have lost their intermediation role.

It does not bode well for ambitions of an upper-middle-income economy status.

It is not the first time the government has painted a rosy picture. Ncube has in the past declared zvakarongeka (it’s all in order) despite lived realities projecting a different picture.

There is a problem if the number does not correspond with what is obtaining on the ground.

Growth must not be superficial. It must be visible in the lives of people. It must be seen in people’s pockets and balances at banks.

That deposits are transitory in nature portrays the true picture — a tough economy where people are struggling to make ends meet. Citizens cannot save because their salaries are low.

When interest rates are over 30%, it means one cannot borrow at such usurious rates.

When annual inflation is at 32,7%, it shows that prices are some of the highest in southern Africa.

That banks are awash with local currency and no one is coming to withdraw is indicative of either of two things: depositors do not have money to withdraw or the re-dollarisation pace is quickening.

When citizens sing or gyrate for cars, which are dished out like confetti, it paints a different picture of the economy.

It tells the economy is in the hands of a few who do not produce anything, employ a few, but rake in millions. And they throw away money unprovoked.

An economy where citizens are taxed to death because the informal sector is outside the tax system is still a long way from attaining an upper-middle-income economy status.

The opposition, supposedly the government-in-waiting, should have checked or rebutted Ncube's remarks.

However, the opposition has been silenced with some tokens.

Citizens are on their own to interrogate the rosy numbers. Numbers must tally with lived realities. It must never be a numbers game.