ENVIRONMENTAL governance in Zimbabwe is no longer an aspiration for local authorities, it is already established.

Across urban councils and rural district councils alike, environmental officers are in place, town planning departments are functioning, and environmental health teams are active.

This did not happen overnight.

It is the result of years of legal reform, institutional adjustment and professionalisation within local government.

The more useful conversation today is, therefore, not about capacity gaps or missing structures.

It is about how these existing systems are used and how much influence environmental considerations actually carry in the decisions that shape towns, service centres and rural settlements.

Anyone who spends time with local authorities knows that environmental governance is most visible when there is a problem.

When a wetland is encroached upon, when flooding damages roads, when waste management fails or when public health risks emerge, councils respond.

- ‘Israel trying to ignite a religious war in occupied Jerusalem’

- Africa Ahead spruces up 25 healthcare centres in Manicaland

- Lock brothers celebrate success in Colombia

- Hit hard by storms and forest loss, Zimbabweans building stronger homes

Keep Reading

Officers investigate, reports are written and corrective measures are taken.

This work matters and should not be dismissed.

It keeps communities functioning.

What is less visible, but increasingly important, is what happens before these problems arise.

Decisions about land allocation, settlement layouts, road alignments and infrastructure investment quietly set the stage for future environmental outcomes.

In many councils, these decisions are still driven primarily by immediate development pressure, political urgency or financial need.

Environmental considerations are acknowledged, but often later in the process, once options have narrowed.

This is not a failure of law or policy.

Zimbabwe’s constitutional and local government framework already places environmental protection at the heart of development.

Councils have clear authority over planning, land use and public health.

Environmental governance was never meant to operate on the sidelines.

The issue is one of practice: how routinely environmental thinking is brought into everyday decision-making.

Other countries illustrate this point, not because they offer templates to copy, but because they normalise a different habit of governance.

In the Netherlands, environmental considerations are simply part of how planning decisions are made, especially where land and water interact.

Environmental input is expected early, not requested later.

Zimbabwean councils already have town planning systems capable of doing the same, both in urban and rural contexts.

In parts of Germany, local authorities approach environmental governance less as regulation and more as asset protection.

Infrastructure is planned with long-term conditions in mind, reducing repair costs and service disruption.

For Zimbabwean councils operating with limited budgets, this is not an abstract idea.

Poor environmental decisions translate directly to damaged roads, blocked drainage, unsafe settlements and rising maintenance costs.

None of this requires new institutions.

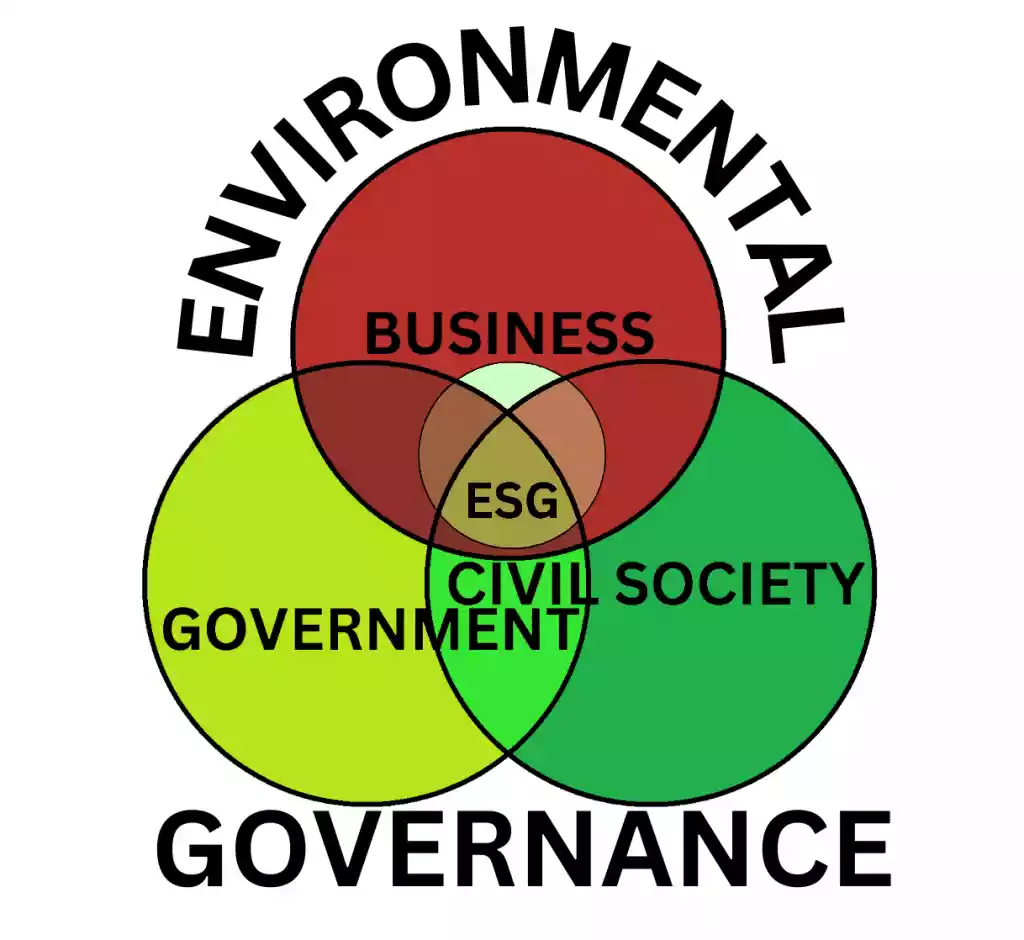

Environmental officers, planners and engineers already sit within council structures.

What matters is how often their perspectives meet at the point where decisions are made.

When environmental considerations are treated as routine rather than exceptional, councils are better able to balance development ambition with long-term viability.

Community involvement also deserves more attention, not as a slogan, but as a practical tool.

Zimbabwe’s local governance system is built around ward structures and local consultation.

These platforms are often used to communicate decisions, but they can also help to shape them.

Involving communities in waste management, land-use awareness and environmental protection reduces enforcement costs and builds shared responsibility.

Experience from Sweden shows that when residents are treated as partners, compliance improves, and trust grows.

This is not foreign thinking; it aligns closely with Zimbabwe’s own decentralised traditions.

Environmental governance also has a financial dimension that councils cannot afford to ignore.

Flood damage, infrastructure failure and public health emergencies place real strain on council budgets.

Preventive planning informed by environmental considerations is often cheaper than repeated crisis response.

In this sense, environmental governance is not an added burden, but a way of managing risk in a constrained fiscal environment.

The discussion around environmental governance in Zimbabwe’s local authorities would benefit from a shift in tone.

Much has already been achieved.

Councils have the structures, professionals and legal backing they need.

The challenge now is to use these tools more deliberately and more consistently.

As climate variability and development pressures intensify, councils that bring environmental thinking into routine decision-making will be better placed to protect infrastructure, sustain services and maintain public confidence.

Environmental governance does not need to be dramatic to be effective.

When it quietly shapes everyday choices, it does exactly what it is meant to do.