THE play Muchazondida is theatre that entertains, unsettles and demands accountability.

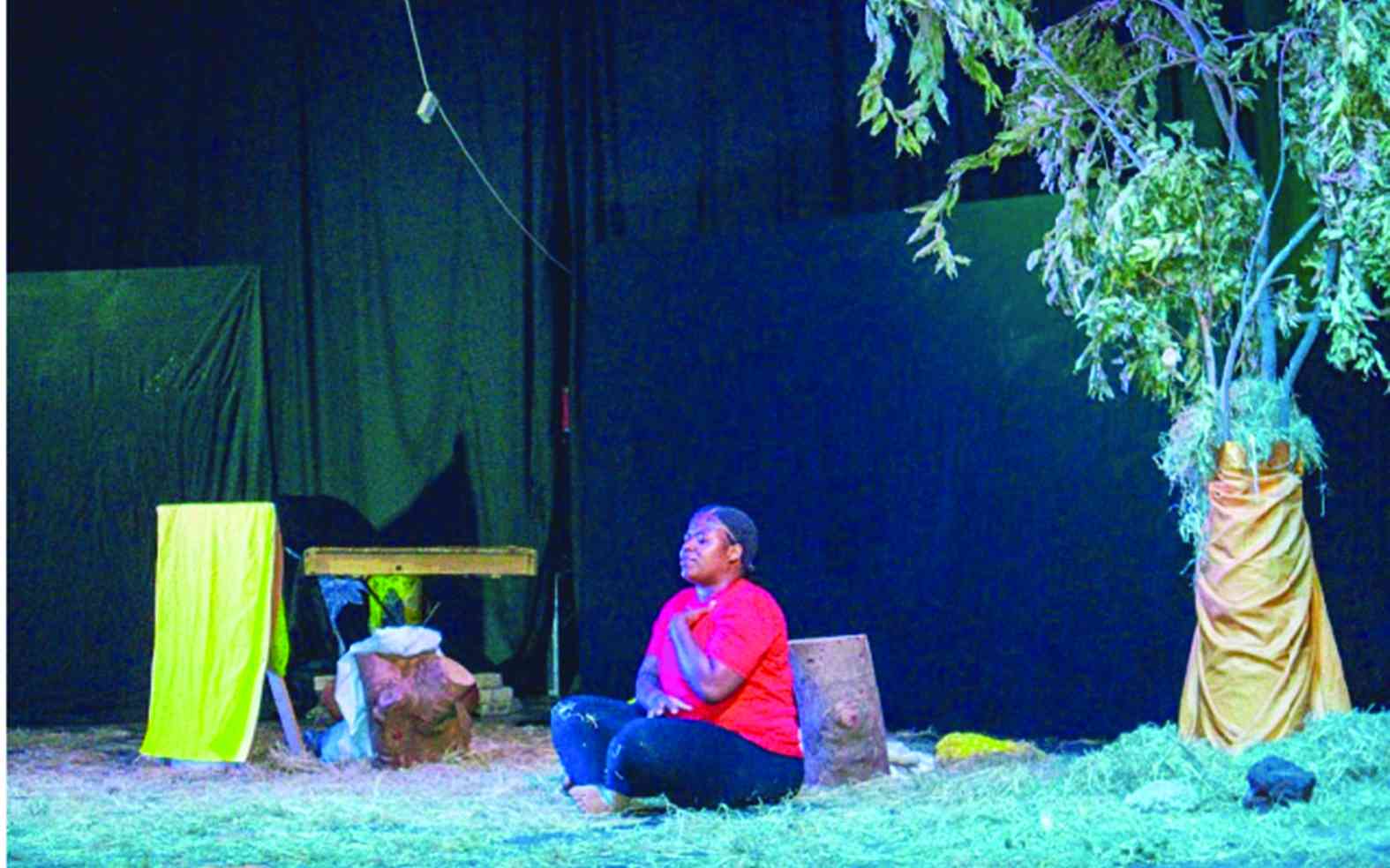

From the moment Edith Masango stepped onto the stage at Theatre in the Park last weekend, it was clear that this was not merely a performance, but an artistic statement confronting how society views disability.

Anchored by a commanding solo act, the production unapologetically exposes the myths, silences and structural injustices surrounding people living with disabilities.

The story is partly drawn from Masango’s own lived experiences as a visually impaired woman navigating stigma, exclusion and resilience in Zimbabwe giving the play personal depth that resonates long after the curtain falls.

Masango, Zimbabwe’s first visually impaired performer to headline a one-woman theatrical production, brings remarkable energy and discipline to the stage.

Watching her perform, one could easily forget that she is blind.

She shifts between costumes effortlessly and without assistance, transitions flawlessly between characters and incorporates dance into storytelling.

Her voice — playful, wounded and defiant — anchors the production from beginning to end, holding the audience in careful suspension between laughter and discomfort.

- An Act of Man comes to Theatre In The Park

- Jeys Marabini takes Xola to Harare

- Gwevedzi returns to Theatre in the Park

- All set for LitFest Harare 2025

Keep Reading

Co-written by Special Matarirano and Fungai Chinogaramombe, and directed by Ratidzo Eunice Tava, Muchazondida tells the story of a third-born child who entered the world “different”.

The play interrogates how disability is framed through economic hardship, religion, tradition and social stigma, and how these forces shape decisions made about people with disabilities, often without their involvement.

While other children played freely outdoors, Muchazondida was kept indoors, hidden, protected, restrained.

Her blindness became a reason for confinement rather than care.

The village did not see a child; it saw a curse.

The community whispered.

Her disability was described as punishment, her existence explained away through superstition.

She grew up carrying a shame imposed by others, so heavy that her father abandoned the family soon after her birth.

In moments of quiet vulnerability, Muchazondida asks the question many marginalised people are rarely allowed to voice: Why was I created like this?

Education, like freedom, was denied.

She was told she belonged in a “second-class” school, if anywhere at all.

Instructions followed her everywhere, never go out alone, never trust yourself, never dream too big.

The play also confronts the gendered realities of disability.

When she began menstruating at the age of 12, instead of guidance, she is met with fear, particularly from her mother, who worries about her vulnerability in a society that dehumanises her.

Her body becomes another site of anxiety and control.

Through sharp storytelling, Masango exposes persistent stereotypes, the assumption that disability is synonymous with begging, dependence or uselessness.

Eventually, Muchazondida goes to school and later seeks employment, only to face repeated rejection because of her blindness.

Determined to survive, she turns to sewing pillows and cushions with her own hands.

The play takes a darker turn when Muchazondida encounters a wealthy man who nearly deceives her into marriage.

His hidden intention is to use her for ritual purposes, driven by the dangerous belief that her blindness, and even her virginity, can bring him fortune.

It is a chilling reflection of how exploitation often hides behind affection and opportunity.

Yet the story refuses to end in tragedy.

Muchazondida applies for a scholarship to pursue her childhood dream of becoming an optical surgeon.

She excels academically and graduates as a top student.

In a dramatic shift, a prominent businessperson offers to help her to establish a multi-department hospital providing free treatment to the community.

Her name, Muchazondida, meaning “You will one day love me”, ultimately fulfils its promise.

The same community that once pitied and stigmatised her now celebrates her achievements.

She returns home to a hero’s welcome, having built a hospital that serves those who once doubted her worth.

This is not the first time playwright Matarirano has explored disability on stage.

His earlier play, Narratives from the Dark, also featured Masango in a solo role and became widely acclaimed for exposing disability-related stigma and discrimination.

Matarirano describes his motivation in deeply personal terms:

“The world needs hope. I have been a soldier and saw how war and poverty can destroy the beauty of life,” the playwright said.

“Hence, I have chosen to help those whom society considers less human and to champion motivation and opportunities for their growth.

“I, therefore, refer to myself as a citizen soldier, fighting for the upliftment and plausible development of such people.”

That mission continues with plans to take Muchazondida beyond Harare.

“We are arranging the national tour for the Muchazondida theatre play as we speak, starting with Kadoma’s Campbell Theatre, tentatively on February 28, 2026. We are also working to source funds for the national tour,” Matarirano said.

“Muchazondida is a powerful conveyor of the story of disability; hence we want to reach every corner of the country.”

Tava, the director, admits the project initially presented an unusual challenge.

“I was approached by Mr Matarirano, who said, ‘There’s a play I have written, but the cast member is completely blind.’

“I knew it was going to be a challenge, but I had faith that I would succeed, though I did not know how.

“The first day I got into the rehearsal room I struggled with how and where to start from.

“I was blank, but after a few minutes ideas started coming. More ideas came with every rehearsal and things started flowing.”

The play closes with a wedding, a symbol of choice, self-recognition, and dignity reclaimed.

Enhanced by live music from Tanaka Mwanangeni, Muchazondida is intimate, unsettling and deeply necessary.

It challenges audiences to confront their complicity and asks difficult questions about how society treats those it deems “different”.