ZIMBABWE’S current economic woes were self-inflicted and the ruling party, Zanu PF, should take full responsibility for the demise of the economy.

Business Analysis: Mthandazo Nyoni

For instance, the country has a habit of violating its own Constitution, ignoring economic fundamentals as well as international rules on how a nation should govern itself.

As a result, the country is currently suffering from a severe economic meltdown coupled with liquidity challenges and company closures, among others.

This article will try to look at factors which led to Zimbabwe’s economic decline. These include political violence or expediency, corruption, introduction of bond notes, just to mention but a few.

Political violence

Just recently, after the July 30 harmonised elections, the army was deployed to quell an MDC Alliance protest over Zimbabwe Electoral Commission’s delay in announcing presidential poll results.

In the process, the army fired live ammunition, resulting in seven people losing their lives and many injured.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

As if that was not enough, a day after the shooting incident, the police tried to block an MDC Alliance-organised Press conference, arguing it was not legal.

These two incidents happened in the full glare of the international community, thereby painting Zimbabwe as a violent nation not suitable for foreign investment.

Therefore, it won’t be surprising to see investors shunning Zimbabwe and opting for peaceful nations in the region. No sane investor would want to put his money in a lawless country afterall.

Political expediency

Zimbabwe loves to make decisions anchored on political considerations. For instance, former President Robert Mugabe made unbudgeted payouts to war veterans when he realised that his political life was in danger.

This, compounded by Zimbabwe’s military foray into the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998 to support the Laurent Kabila dynasty, helped precipitate currency collapse and hyperinflation of the early 2000s.

Again, Mugabe seized white-owned farms, wrecking the agriculture sector and triggering hyperinflation, with gross domestic product nearly halving between 2000 and 2008 — the sharpest contraction of its kind in a peace-time economy.

Economic analyst Godfrey Kanyenze said political violence has crippled Zimbabwe.

“That was long before even land reform. Then we started beating up people after the February 2000 referendum, we started beating people under fast-track land reform programme and the international world responded and condemned it. Then we spurned the narrative around it and we came up with the sanctions narrative. The whole economy collapsed because we mismanaged it and we were corrupt,” he said.

Economic commentator John Robertson said when land seizures came at the end of the 1990s, government removed the collateral value of billions of dollars worth of land that had previously supported the country’s business sector.

Commercial agriculture was also the country’s biggest export earner, biggest employer and supplier of inputs to the manufacturing sector. Its foreign currency earnings enabled the country to obtain international credit, to meet its debt service obligations and to build foreign reserves that supported the value of the local currency.

“Zimbabwe lost its ability to function properly in all these areas when commercial agriculture was so badly damaged. Thousands of jobs were lost, international debts could not be repaid, food and many manufactured goods had to be imported, tax revenues fell so sharply that money printing became necessary and the resulting hyperinflation destroyed the Zimbabwe dollar,” Robertson said.

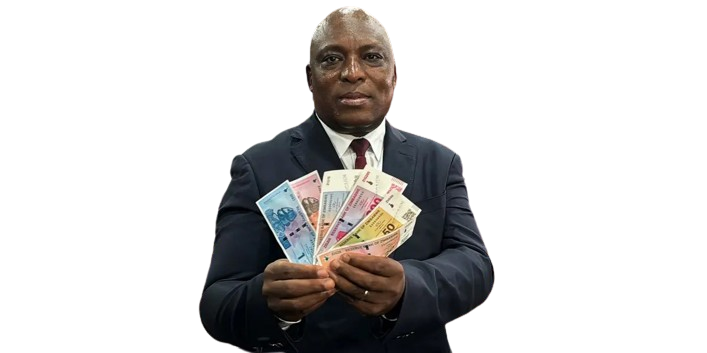

Bond notes introduction

In 2009, Zimbabwe was forced to abandon its currency — which had gone up in an inferno of hyperinflation — and to adopt the US dollar as its principal means of exchange. The enforced dollarisation stabilised the economy and led to an initial 40% rebound in incomes, though these have since flat-lined.

With no local currency, money supply became entirely dependent on inflows of US dollars, in effect depriving the authorities of control over monetary policy.

In a desperate measure to introduce liquidity, government introduced bond notes in 2016. These were theoretically backed by hard currency, but have quickly deteriorated in value.

Money supply has surged more than 30% in the past year and the notes plunged 60% on the parallel market.

Violation of laws of economics

Robertson said from 1980, Zimbabwe’s economy was rendered increasingly fragile by measures that were intended to weaken the influence of existing productive sector leaders and enterprises, not to make the economy stronger.

The 1980s were characterised by confiscations of import licences, tightening of exchange controls, higher taxes, higher minimum wages, more difficult labour laws and increasingly restrictive investment regulations.

“These all discouraged the investment inflows that were needed in manufacturing and in other productive sectors. Assistance from the World Bank and IMF [International Monetary Fund] in the early 1990s was rendered ineffective by government’s failure to meet the agreed conditions,” he said.

Kanyenze said: “We have really violated our own Constitution, all the laws of economics, all the international rules on how a nation should govern itself and then at the end we have the audacity to say its sanctions. That is weak governing.

“This is our journey as a country; we can’t be blaming other people. For example, you complain that there is no foreign currency in the country and we find a nice narrative we say it’s because of sanctions. We defaulted on our debt in 1999.”

Robertson said government’s habit of imposing more controls to overcome the problems, was worsening things.

For instance, government forced the surrender of all foreign earnings, swapping these for local dollars of rapidly falling value. Over the foreign reserves, government imposed absolute control and even more companies were forced to close.

Then, when dollarisation allowed the relaxation of exchange controls and stimulated a recovery in investor interest, government empowered itself to seize and redistribute company shares through its Indigenisation Act.

“Mining company assets, profits and reserves came under separate attacks in the form of additional taxes, biennial registration fees for mining claims and confiscations of title to legally pegged and registered mineral deposits. But for these, mining investment would have been very much higher,” he said.

Lack of vision

Zimbabwe as a country lacks vision and this has killed it, says Kanyenze.

“We need a vision as a country. If we don’t have a vision the people perish as the Bible says. Our problems are of our own making. Look at the budget deficit right now. During the GNU [Government of National Unity], Tendai Biti (former Finance minister) came up with his mantra that you eat what you kill,” Kanyenze said.

He said Biti adopted a cash-budgeted framework and the country almost had a balanced budget.

“But after 2013, Zanu PF took over. What happened? They took over all those debts, through the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. Previously, we had agreed that those who benefited should pay, but in 2013, the government said we will take over. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellency, therefore, is not an act, but a habit,” he said.

“You become what you continuously do. If you continuously mismanage your fiscus, like what we have done, you end up with this scenario, where now we didn’t have that much of a budget deficit or domestic debt when one party took over in 2013. Now we have a serious domestic debt,” he said.

Exchange controls

Falling confidence, disappearing bank notes and low investment inflows in the 1990s prompted the return of exchange controls and the forced surrender of foreign earnings, again in exchange for money of falling value.

Robertson said enormous costs were imposed on the economy by these measures, but they were all chosen by politicians.

“Sanctions were imposed on individuals who were accused of human rights violations and some government-run enterprises, but they were not responsible for halving the country’s Gross Domestic Product,” he said.

“The falling export revenues, inability to settle debts, shrinking tax revenues, negligible investment inflows, collapsing infrastructure, liquidity shortages, loss of savings, unstable banking and increasing poverty were all caused by government policy decisions that should never have been taken.

“Their costs to the rest of the population could be measured in the lack of employment growth, but this would miss the point: hundreds of thousands of jobs were actually destroyed. Through the adoption of corrupt practices, government officials were able to side-step the penalties and often to profit from the mounting chaos,” he said.

Corruption

Zimbabwe has been ranked number 157 out of 180 countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2017 by Transparency International. Due to that, investors have shunned the country opting for corrupt-free countries in the world.

President-elect Emmerson Mnangagwa, who came to power through a military coup last November, has dismally failed to curb corruption. For instance, recently, police in Harare arrested four people after they were found in possession of $4 million cash and 100kg gold which they could not account for. As of today, it’s not clear what happened to those people, whether they were taken to court or “freed”, only God knows.

Economic commentator Reginald Shoko said the economic woes Zimbabwe was facing “are a result of a cocktail of challenges — some self-inflicted like the indiscipline, mismanagement, policy inconsistency and corruption. On the other hand, it’s the effect of our isolation from the international community.”

Way forward

Lovemore Mbigi, a professor of business and public management, said there was need for leaders to be accountable for their actions.