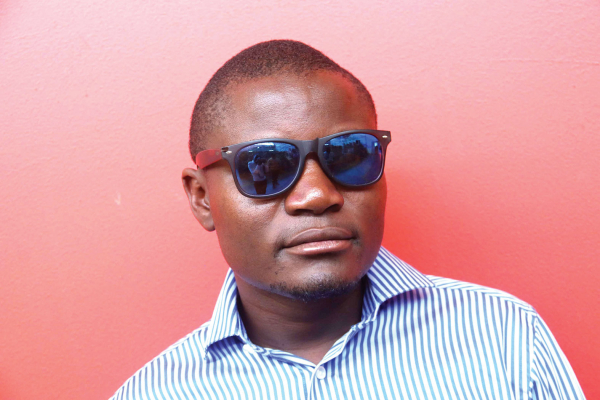

THERE is a young man in Highfield, who believes he is going to be a top musician. He calls himself Ghetto.

Tapiwa Zivira

Whenever I meet him, Ghetto often looks inebriated, but in all our conversations, he always asks: “Do you have a flash disk, so I can upload my latest songs for you?”

Ghetto believes that since I am a journalist, I can be the gateway to his dream of becoming famous enough to share the stage with great musicians.

Interestingly, when I offer him my memory stick, he then asks me to accompany him to the local backyard studio where the recorded songs are stored.

“Unfortunately, I don’t have the songs with me here. They are at the studio,” he always tells me.

We often part without me getting anything from him. But, of course, Ghetto is not alone in this game. He is one of the many unemployed young men and women trying their luck in music.

Out of desperation and frustration of just sitting on street corners, without any hope for a better future, these youngsters resort to the backyard studios, where they try their luck on the microphone.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The studios, in turn, are a result of the increased access to information technology equipment, and to a greater extent, they are a result of the unemployment crisis.

Often made of makeshift material, where sound buffers are replaced by empty egg crates nailed across the walls; the studios are very basic. So for Ghetto and others who hope to make it like Soul Jah Love, Seh Calaz or Kinnah, who came from the same situation, the ghetto studios are the beginning.

This is a new trend. It is a new way of making music, where budding artistes can freely distribute their music or charge a nominal fee to send it via the WhatsApp instant messaging platform.

They are not tied by any copyright and distribution bottlenecks like in the old set up, where recording companies had unlimited rights on music, and the artiste was relegated to being just the musician.

All what these youngsters do is pay, say $5 or $20 depending on the studio, and they can ride on any riddim, and once it is done, they get a copy of their music and can distribute it anywhere and at any charge they wish. Often no papers are signed, and the agreements are just verbal.

Yes, for some studios and producers that use the same method, but have sailed above the amateur level, the fee is much higher and contracts are signed between the studio and the artiste.

However, all this has sort of turned over the way music is made and distributed.

Where latter day musicians, mostly in dancehall, do not worry much about sales and just hope to be visible, earlier musicians, like your Alick Macheso, among others, still worry about piracy and want to adhere to the traditional ways of making and distributing music.

There comes a conflict. In the streets, you find people selling copies of CDs by musicians from across genres. Younger artistes would be happier that their music is going places, while older musicians would want to thwart the practice right away.

In these circumstances, drawing parallels between the two is not so easy because these are two sides of musicians — one side believes in institutional music-making where one has a whole band and the other is just a one-man band that rides on ready-made riddims.

Piracy is the distribution of music or any form of artistic work, without the permission of the copyright holder. In the case of older musicians, the copyright holder is the recording company, while in the case of contemporary artistes, the copyright is in the hands of the artiste.

So, in terms of distributing music, there needs to be common ground, because often, fighting piracy is believed to involve the shutting down of all illegal outlets that sell CDs in town, and the burning of all memory sticks, and laptops, and computers and handsets that carry music.

But this is 2018, and there are so many devices that can carry music. There is the internet, where people can freely share or buy music.

In other developed countries, particularly the United States, while piracy is still high, they have developed more effective methods of selling copies online and dealing with online copyright infringements.

I believe that it is essential that government, through the arts ministry and the National Arts Council, as well as other stakeholders such as the Zimbabwe Music Rights Association, musicians, journalists, recording companies, producers and band managers, among others, call for a convention on how to formulate proper procedures that will benefit the artiste, especially the budding ones, to get at least a dollar or two out of their works.

With enough education, empowerment and with access to proper channels, I believe youngsters like Ghetto can have a platform where they can sell, for very little, their music. The public also needs to be educated to stop believing that what is on the internet is for free!