Georgy Egorov, an assistant professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at the Kellogg School of Management; his colleagues Daron Acemoglu, professor at MIT, and Konstantin Sonin, professor at the New Economic School in Moscow, opine that competency of government can be described by mathematical models. Among several other attributes, they mention that democracy is not necessarily a good omen for good governance, but is critical. As a liberal, I am also excited to note that a government tends to be better when it is smaller and abstains from unnecessarily meddling in lives of citizens.

guest column: REJOICE NGWENYA

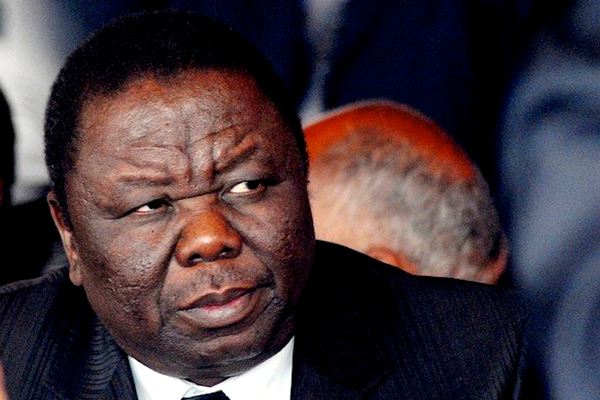

Last week a colleague and I sneaked into Zimbabwean opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai’s palatial manor in Harare to witness him sign a memorandum of electoral understanding with fellow political activist professor Welshman Ncube. This was the first time I saw these two together since early 2000 during my rookie years in political strategy at Harvest House. I got excited seeing old pals — complete with grey hair — Ian Makone, Morgan Komichi, Miriam Mushayi and, of course, the emerging generation in the likes of Sydney Chisi, Nelson Chamisa, Michael Mukashi, Luke Tamborinyoka and Kurauone Chihwayi together after a decade as political adversaries. Many questions went through my mind — one of which was: Given that Tsvangirai now seems to be “de facto” coalition leader, when opposition defeats Mugabe in 2018, will he make a better leader than the catastrophic 93-year-old?

It is easy for fanatical legions of Tsvangirai supporters to dismiss my question with “Yes, Tsvangirai will obviously make a better President than Mugabe”, but my experience in life — I will be 57 this year — is that some things are easier said than done. In 1980, still in my late teens, my late friend Evans “ZEX Airlines” Ndebele and I huddled around a Trident double cassette shortwave radio at Figtree Hotel, River Road, Nairobi in Kenya listening to the then young Robert Mugabe proclaim: “So help me God.” We assumed he meant “Help me not only to uphold the Lancaster House Constitution, but also to be a better leader than the racist Ian Douglas Smith.” I bet had Evans been alive today, huddling at our usual watering hole at the Oasis Hotel in Harare, he would have said, in his usual language: “Ron we were wrong. This government has turned out to be run by a mother f*****g a*s h***s whose leader blatantly lied to God”.

And so, 37 years later, I now ask myself the same question: “If — or is it when — Morgan Tsvangirai becomes Zimbabwe’s second democratically elected President, will he be better than Mugabe?” Let me delve into the realm of intellectual comparative analysis to avoid being labelled too simplistic. I have observed above how Egorov has already proved that good government is actually a product of rocket science. Mere verbal pronouncements, party slogans and hero-worshipping cannot turn Tsvangirai into a better leader than Mugabe. There are specific indices of performance we will use to judge him — and not after 37 years — but before and immediately after he assumes power.

First of all, despite being head of a coalition government, numbers of his government ministries and civil servants are critical. Mugabe has more ministries than the government of India, a country with a population 1 000 times larger than Zimbabwe. His $4 billion National Budget is smaller than Pick N Pay’s and his country’s economy is 100 times smaller than that of a “small province” called California in the United States. Mugabe’s civil service is so bloated that he forks out 98% of the fiscal turnover as salaries to 500 000 civil servants. So, in principle, all Tsvangirai needs to do is to just reverse this trend when he takes over, but what lurks in the dark corridors of power is the poisoned chalice of misplaced political ideology. Tsvangirai’s popularity is a derivative of his charismatic reign as leader of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions that co-opted him into National Constitutional Assembly politics in the late 1990s. He is a social democrat obsessed with welfare State mentality, thus it is difficult to see how he will resist the temptation not to dismantle a dysfunctional, human capital intense public service system. And that is only part of the problem.

After almost 20 years languishing in the opposition trenches, Tsvangirai’s political eureka moment will come with a notorious non-return valve that fails to keep pressure from the legion of his subordinates pushing for government positions. My experience of him during the Government of National Unity era is that he will let all existing government positions simply remain only to be occupied by MDC-T praise singers as “reward for your sacrifices”. Coupled with the desire to prove his socialist ideology, public expenditure in social programmes and non-profit yielding infrastructure will skyrocket, and before you know it, our budget deficit and public debt will be Mugabe-like. If, as expected, the Bretton Woods institutions do a “neo-liberal thing” on him — which is good! — the “Marshall Plan” and its related frenzy of foreign direct investment inflows (assuming he restores private property rights) will flood the investment market with billions of dollars. Tsvangirai’s parasitic cronies will fail to resist the temptation of dipping their fingers into the national Treasury for self-aggrandisement. Usually such money, especially for “poor leaders who have access to power”, is much too tempting. Corruption is not just in the DNA of Zanu PF — it is a national scourge that Tsvangirai will have to confront.

And so, let me conclude. If Tsvangirai wants to be better than Mugabe, I have a few indicators he should adopt for a new Zimbabwe.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

According to the Legatum Index Government Ranking, Switzerland, New Zealand, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Luxembourg, Canada, Norway, the United Kingdom and Australia boast among the best well-run governments in the world. In these countries, it is the democratic vote that gives citizens the most political power. Legislative power lies with Parliament while a President presides over a tight Cabinet that supervises an “excellent health care system, top-notch educational programmes, low levels of air and water pollution, freedom of speech, the right to responsibly defend oneself, a priority given to innovation, and a stable economic environment”.

I can imagine that free markets reign supreme, private property rights are respected, while government seeks wise counsel of the private sector. Zimbabweans have to trust Tsvangirai to live up to his promises of giving us an opportunity to reclaim our lives, create our own jobs and be happy. He must employ few, but effective, creative and hardworking government workers rewarded only for excellent performance, not for political allegiance.

Unlike Mugabe, Tsvangirai must deal decisively with corruption. MDC-T-run local authorities in Mutare, Chitungwiza, Harare, Gweru and Bulawayo are already showing signs of pervasive corruptive tendencies that Tsvangirai has failed to eliminate — and that is not a good sign of an effective gaffer. Finally, as Calvin Coolidge says “Without character — which includes humility, moral courage, passion for public service and honour — leaders become poisonous to their organisations.” I rest my case.

Rejoice Ngwenya writes in his personal capacity.