It is the morning of December 12, 1978 when the country woke up to news of the attack on Rhodesia’s largest fuel depot in Southerton, Salisbury.

The attack resulted in a huge blaze, which destroyed millions of gallons of fuel.

It was undertaken in the evening of December 11, 1978, and is often described by those in power today as the most “historic day” in the liberation of Zimbabwe.

It remains debatable who really masterminded the attack as both Zipra and Zanla claimed responsibility of what was described by then Rhodesia Prime Minister Ian Smith as “the worst disaster in six years since the war began”.

Those who masterminded and bombed the depot are the same people who have become our “heroes” today.

They are heroes because they weakened Smith’s regime. Some were rewarded for that act of “bravery”.

But in the Smith regime’s eyes, they were terrorists or economic saboteurs, who were bent on undermining a legitimate government, even when that legitimacy was under domestic and international scrutiny.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Just like we read today, the Rhodesian government had stopped caring about international opinion.

Unlike today, Smith’s regime had developed coping mechanisms to mitigate the impact of isolation to become a self-sustaining country than blaming sanctions for everything that went wrong.

The attack at the fuel depot was a big blow as it drained millions of gallons of fuel from the country’s already limited resources and would rob the economy of an estimated $9 million at the time, and much more in the long term.

At any given time, Rhodesia maintained fuel reserves to last seven weeks, and that too became unsustainable.

Fuel queues fast surfaced around the capital city and surrounding towns as people stampeded to stock the already scarce resource amid renewed fears of an imminent state of emergency to thwart further guerrilla manoeuvres.

For a country suffering isolation due to international sanctions and facing global pressure to reform, it became clear that the racist policy arrogance by the Smith regime in a season where the winds of change were inevitable, was running out of steam.

Rhodesia faced three tough choices. They could choose to save Africa’s second largest economy by talking to the unrelenting guerrilla fighters who were pursuing a free, independent and democratic society in which everyone, irrespective of their race or political beliefs, would be able to live in secure and peaceful environment.

Or second, they could choose to pursue arrogance against people and the guerrilla fighters who had nothing much to lose as the regime had already stolen their dignity and watch as the economy dissipated under their watch.

Third, Smith had a choice to destroy the economy as happened in Mozambique, parcel and pocket it and flee, leaving the country on its knees.

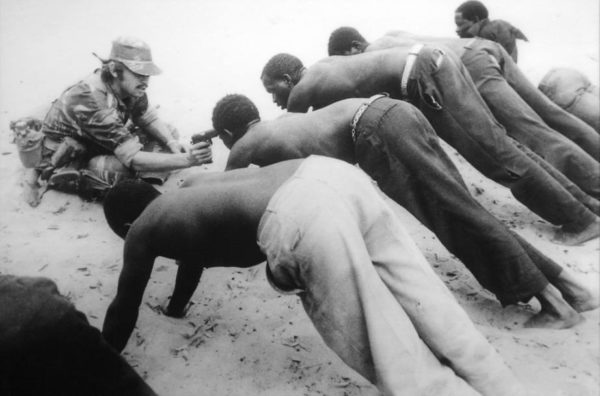

It was pretty much clear that the liberation fighters were determined to cripple the Smith regime into submission. Part of the strategy was to sabotage key national utilities such as energy and water supplies, including supply routes.

The thinking behind was that unless the Smith regime was brought into some form of destitution, it would be difficult to bring his system to the negotiation table or to make them understand the urgency of independence for Zimbabwe. Therefore, something had to be sacrificed.

The economy, which provided the life-line for Smith’s system, became the target not for bad intentions, but to expedite freedom for the black majority.

Despite denials by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the economy, indeed, took a huge knock from the attack. It was clear that Smith would be arm-twisted to the negotiations table if he was to please the white constituency by saving the economy from further destruction.

And indeed, it laid the foundation for further discussions. While Smith’s regime flagged several proposals, which were meant to delay independence or keep his system in power post-independence, it was clear that change was inevitable and that he was aware that anything short of immediate independence would result in further damage to the economy. He chose to preserve the economy.

This realisation would inform Smith’s position ahead of the Lancaster House discussions in 1979 and the subsequent independence of Zimbabwe in 1980 that preserving the economy was crucial for the future of the country.

He knew that there was more to lose from being arrogant and he needed to act in the interest of preserving the economy he had built over the years.

More than 36 years after independence, Zimbabwe finds itself in an almost similar situation as if history is repeating itself.

The people are angry that they don’t have jobs and access to services. Poverty and suffering have become the order of the day. They seek their government’s audience and none is coming.

They have resorted to protests and there is no response from their government other than teargas and water cannons. When one knocks on the door several times and they don’t get a response and they know for certain that there is someone inside, the next move would be breaking down the door.

These are some of the signs of what was witnessed last week with the burning of assets and infrastructure. It is not good, but perhaps, it can be minimised by giving them attention.

Tapiwa Gomo is a development consultant based in Pretoria, South Africa