SPECIAL REPORT BY EVERSON MUSHAVA

African liberation fighters drew inspiration from revolutionary music. Social commentaries of the prevailing injustices belted out in song would motivate liberation fighters and deepen their understanding and resolve to the liberation cause.

SPECIAL REPORT BY EVERSON MUSHAVA

African liberation fighters drew inspiration from revolutionary music. Social commentaries of the prevailing injustices belted out in song would motivate liberation fighters and deepen their understanding and resolve to the liberation cause.

Zimbabwe’s 1970 liberation struggle against Ian Smith’s rule also created celebrated musical icons who churned emotionally-charged songs that rallied the freedom fighters until liberation was won in 1980.

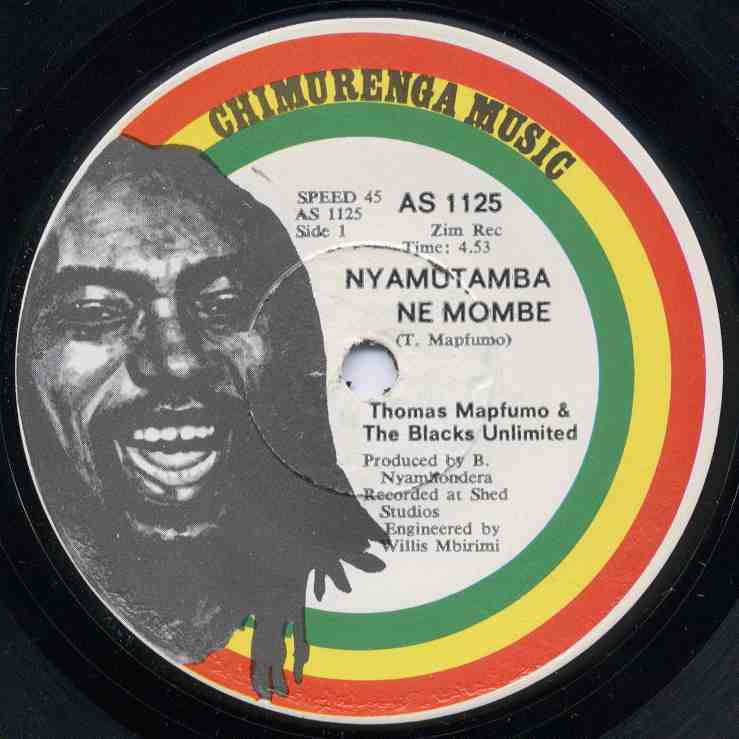

Notable is Blacks Unlimited frontman Thomas Mapfumo. A multitude of his fans call him Mukanya after his totem, the baboon. Due to his bravery which dates back to the liberation struggle, others call him “The Lion of Zimbabwe.”

A legion of his fans in America, where he is self-exiled for the past decade, call him Hurricane Hugo, after the storm that destroyed buildings, leaving millions stranded, the same year Mukanya arrived in America and held his first massive gig.

Some call him Gandanga (rebel), for his rebellious approach to the ruling elite. He is also called Tafirenyika, a name that was coined after his undisputed contribution to the liberation struggle through music.

In 1999, Mukanya was bestowed with an Honorary Master’s Degree from the University of Zimbabwe for his sterling contribution towards the shaping of societal values through his music career both in pre- and post-independence Zimbabwe.

Most people believe Mukanya is one of the finest international musicians Zimbabwe has ever produced.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

His Chimurenga genre that fuses the traditional mbira beat, drums and guitars and other western instruments has always left his fans clamouring for more.

More captivating in Mapfumo’s music is his messages that exude arrogance and wisdom. Unlike other musicians who are paradoxical, Mapfumo is often direct and combative. The urge to think that the 67-year-old music maestro is reckless is also tempting.

The dreadlocked musician’s messages would continue to inspire many generations, but it is his post-independence catalogue that is more intriguing.

Mukanya, as profiled by Kristina Funkeson, began his musical career at a tender age of 16. He played mostly American rock and soul covers before he shifted to his Chimurenga beat in the early 1970, which is a fusion of the western beat with the traditional Shona mbira beat.

At that time, Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe was under Smith’s rule. Mukanya’s lyrics soon became very political against white minority rule, supporting the armed struggle. He called his music Chimurenga, the traditional Shona word for “struggle”. Chimurenga was also a name for the black majority’s revolutionary movement against white colonial rule.

Since then, Mukanya had stood for the “struggle” fighting colonialism with the “power of his music.” His music was very militant, calling for the overthrow of Smith’s government by any means. But because he composed in Shona, the whites took time to appreciate the influence of his music to the struggle.

But in 1979, his hit song, Hokoyo – a threat to the white ruling elite – brew trouble for him. He was arrested without charge and released three months later after fierce protests from the people over his arrest.

Garotumira Vana Kuhondo was also one of Mukanya’s hits that encouraged black parents to release their children to join the armed struggle against colonial rule. The list of his revolutionary hits that catapult him to fame is wide.

In his 34th independence anniversary message to Zimbabwe, Mukanya said: “Even though I was not holding a gun, it was a difficult terrain and I was constantly harassed, arrested and detained because I denounced oppression and colonialism.

“My dream was to see a free Zimbabwe where our citizens are able to access education, health, access to decent accommodation, and above all a better life for everyone.”

“My dream was to see a free Zimbabwe where our citizens are able to access education, health, access to decent accommodation, and above all a better life for everyone.”

Mukanya in 2003 also told The Leopard Man’s African Music Guide. “We would write songs that would encourage fighters, those who were fighting from the bush, fighting for freedom. That type of music actually motivated them to fight fiercely.”

Throughout his career, Mukanya has been a very vocal critique of social injustices perpetrated on the general population by the ruling elite.

“My music stands for freedom and justice,” Mukanya told a web-based American newspaper Kentucky.com.

Political analyst Takura Zhangazha told NewsDay: “A common thread in Mapfumo’s music has been an unrelenting pursuit for social and economic justice, before and after Zimbabwe’s independence from colonial rule.”

Mukanya’s emotionally charged and prophetic music was not only meant to entertain, but to moralise at the expense of reality.

Zimbabwe attained independence in 1980 and the whole country was thrown into months of wild celebration. Mapfumo was not left out.

His dream had been realised. His hit song, Pemberai, summarised it all.

For the first close to a decade after independence, Mapfumo threw his weight on the new Zanu PF government led by President Robert Mugabe.

But it was in 1988 that Mukanya released the controversial song – Corruption – that manifested his disillusionment with Mugabe’s rule. The song officially unlocked Mapfumo’s rift with Mugabe’s regime.

The song came after the vehicle scandal involving top government officials that has come to be known as the Willogate Scandal. In the song, Mukanya criticised government over corruption, calling political leaders thieves.

As social ills continued to grow in post-independence Zimbabwe, Mapfumo released Mamvemve in 1999. The song accused Mugabe’s ruling elite of betraying the promises of the liberation struggle and reducing a rich country to a basket case.

In 2003, Marima Nzara took government head on over the land reform and other pressing economic issues. Baba Munonyanyakupopota was also seen as an attack on Mugabe’s diatribe against the West, whom the veteran musician insinuated played a pivotal role in Zimbabwe’s economic development.

The anti-government stance resulted in his music being denied airplay on national radio stations.

While Mapfumo’s critics would want to suggest that the Chimurenga guru is in a self-imposed exile in America to flee from arrest over criminal charges, others believe he has genuine concerns to fear for his life after his relentless attack on the Zanu PF government.

“He criticised colonial rule during the liberation struggle and went into celebrating mood in the first nine years after the attainment of independence. Mapfumo’s music took a new turn in 1999 when he started demanding that independence should mean more, not corruption, lack of democracy, no respect for people and so on. In 2000, Mapfumo’s music became more direct against the system,” Zhangazha observed.

“Government has not been comfortable with his music, from the time he released the album Chimurenga Rebel to Chimurenga Explosion. National radio stations could not play Mukanya’s contemporary music. He turned radical in 1989 when he felt the values of the liberation struggle were being violated.”

“We thought we were liberated, but we were not”, Mukanya told the American TIME Magazine.

Mukanya told The Leopard Man’s African Music Guide in 2003: “We sing about the problems that the world is facing today. As you know there are so many disturbing situations we hear about like the situation back in Zimbabwe, the situation in Palestine, these kinds of situations are all over the world. There are a lot of people who are not very free in this world. They don’t have their freedom. They don’t have a voice. We as musicians, through our music, we can be their voice.”

To buttress that he represents the aspirations of the struggling masses, Mukanya, in this year’s independence message said: “Our nation must develop, but the worrying thing facing our country today is corruption, instead of working to develop our country there are those selfish individuals who because of their positions of influence are busy stealing from the poor. That must stop; it’s a betrayal of the values of the liberation struggle and our national independence.”

He added: “Independence is not about corruption, it is about honesty, unity of purpose and the love for Zimbabwe. Our people need food on their tables, education, and above all a good life. We must share the national cake equally. Those who are corrupt must be held accountable. We have a task as Zimbabweans to fight corruption. It is tearing our economy apart. In the 1980s I sang about corruption because I had realised that others went to war for selfish reasons. The traits are still manifesting in some comrades even today.”And true to his words, Zimbabwe is currently battling to contain corruption that has destroyed public institutions. Even in the United States, Mukanya has remained resolute in criticising social ills back home.

Mukanya’s self-imposed exile in America has been received with mixed feelings. Some say he has reasonable grounds to fear for his life after scathing attacks on Zanu PF, but others describe him as a coward who ran out of the country to avoid arrest over his own crimes.

His critics say his life was never in danger. They describe him as a revolutionary who had lost the spine and went out on a crusade to demonise the very country he claimed to have liberated.

But his ardent supporters say Mukanya’s experiences save to show the death of democracy in Zimbabwe.

Even if he had nothing to run away from, the denial of airwaves to his music showed that the voice of dissent was not welcome by Mugabe’s government. Mukanya could be one of those many victims of an intolerant political culture.

“There is a political correctness in Mukanya’s songs, but there is no culture of freedom of expression in Zimbabwe. Government has kept on draconian laws to curtail freedom of expression, like the criminal defamation laws,” Zhangazha said.“Mukanya is not the only victim of this, only that he is a legendary victim. Any person who varies in opinion with the ruling elite has been subjected to persecution.”

Another political analyst, Ernest Mudzengi, said Mukanya’s life testifies to the experiences of the liberation struggle.

“Mukanya’s life portrays the struggle for independence and the contradictions after independence. He called people to take up arms against colonialism, celebrated when independence was won and denounced vices such as corruption and dictatorship. Here we see an icon who is in exile far away from the country he fought for,” Mudzengi said.

“What we need is democratic change where people can express their view freely.”

Another political analyst, Wellington Gadzikwa, said Mukanya’s musical history showed that he is a protest musician who applauds something good and castigates the negative. He has kept his legacy as a barometer of the people.

Mukanya, unlike other musicians who use artistic expressions, is direct.

“Anyway in the world, the powers that be are not comfortable with criticism and Mukanya’s career is not an exemption,” Gadzikwa said.

Mukanya’s musical career is testimony to Zimbabwe’s political culture that is not tolerant to criticism. Even in Zanu PF, people who came out open criticising the existing situation have been censored and the same is happening in the main opposition, the MDC led by Morgan Tsvangirai.

Energy minister Dzikamai Mavhaire was side-lined for more than a decade before he bounced back last year for calling for Mugabe to step down. The same is happening in the MDC where calls to have Tsvangirai step down have heavily divided the party.

Mukanya’s spokesperson Blessing Vava said Mukanya fearlessly represents the poor.

“His music has been a source of inspiration to the to the poor,” said Vava adding that the Chimurenga maestro was not running away from anything and would be coming to stage a show back home in September.

Zimbabwe’s politics have been intolerant to opposing views. The leaders want to be worshipped, not criticised and Mukanya could be paying for “seeing and saying evil about the ruling elite”.