BY KUDZAI MAZVARIRWOFA

Sometime around December last year, Simbarashe Chanetsa was in so much pain he struggled to breathe.

He could neither sit up nor eat. He thought he was going to die in his sleep.

“I didn’t go to the hospital,” said Chanetsa, a 33-year-old entrepreneur who battled what he believes was the coronavirus.

“Why? When they do not even have medication for the virus?”

After a couple of days, he turned to steam therapy, as well as alternative medicine and traditional herbs. Chanetsa, whose symptoms included fatigue, loss of taste, a fever and chest pain, never got tested for Covid-19 — the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Chanetsa’s rejection of health care in the midst of a pandemic speaks to how deeply cynical Zimbabweans have become about a system infamous for its expense, inefficiency and lack of personnel and medicines.

Patients’ doubts about the system have compelled some to treat themselves, a risky proposition given the ever-evolving nature of the potentially lethal virus.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Zimbabwe has recorded more than 122 000 cases of Covid-19 as of yesterday. Neighbouring South Africa has had far worse situation than other southern African countries, with more than 2,5 million cases.

“Zimbabwe’s health sector is now moribund,” said David Mukwekwezeke, who worked at a public hospital for three years as a doctor and has written extensively for local media about Covid-19.

“Virtually every health professional working on the ground and the front line can testify to that.”

It wasn’t always so. Back in the 1980s, Zimbabwe’s health care system was renowned for its excellent hospitals and robust primary care.

But as debt and corruption laid waste to the economy in the early 2000s, Zimbabwe’s vaunted health care regime crumbled.

From 2000 to 2007, government spending on health fell by 43%, according to a 2018 article published in Global Health Action, a research journal focused on international health issues.

Some hospitals hobbled along without electricity or running water.

In 2008, government physicians took home less than $1 a month, the article states.

The decline persisted, marked by low government spending, staff shortages and lack of medicines.

Then, in March 2020, the coronavirus arrived.

At the end of last year, after a national lockdown aimed at halting the virus, the government opened its borders, hoping to resurrect the country’s pandemic-paralysed economy.

Instead, new strains made their way in from neighbouring South Africa and elsewhere, further weighing down a health system already well below its capacity.

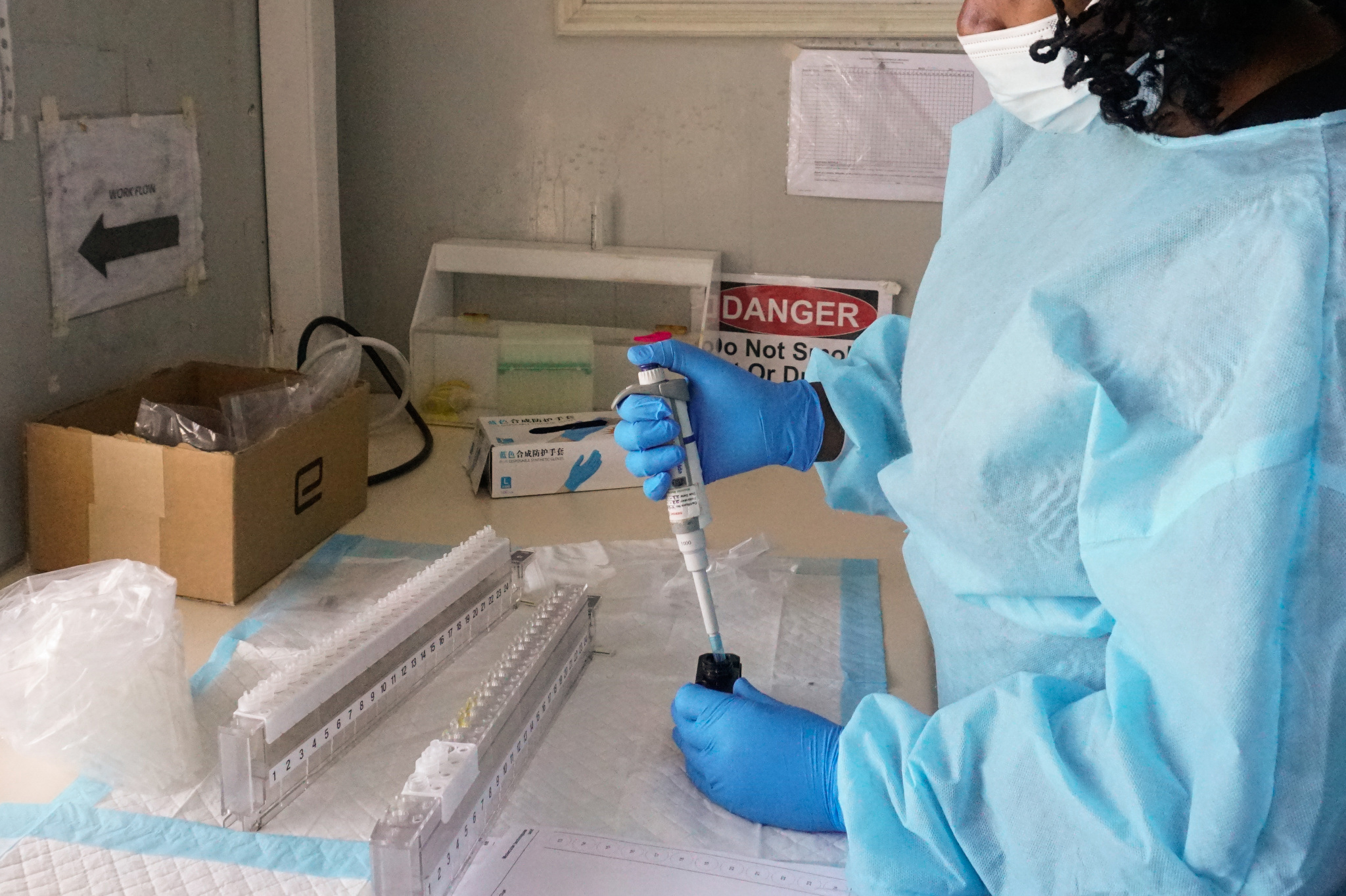

Raiva Simbi, director of the government’s National Microbiology Reference Laboratory, said doctors initially had trouble diagnosing Covid-19, in part because “there were no specific tests” for the disease. “The coronavirus was elusive,” he said. And those challenges only mounted as new strains arrived.

In October, Zimbabwe averaged only 127 Covid-19 cases per week. By January, as new strains flourished, its weekly average ballooned to about 8 000.

By late June, the weekly average dropped to 1 237 cases, well below other southern African countries such as Zambia, Botswana, Namibia and South Africa.

Those who have braved Zimbabwe’s hospitals and health centres echo Chanetsa’s lament.

Sithabile Dewa’s brother-in-law was a 45-year-old chef.

In January, he had trouble breathing and suffered chest pains.

He went to The Avenues Clinic, and after three days, he began to fail, said Dewa, who declined to identify him.

Doctors there said he needed a ventilator, but the hospital had none.

The family went from hospital to hospital — both public and private — in Harare, trying to find one. But each time, Dewa said, “either the hospital [was] full or didn’t have nurses to attend to patients.”

“Unfortunately, he passed away less than 24 hours after we started looking for the ventilator,” Dewa said. He was sick for less than a week.

It can take days for doctors to diagnose new strains of the virus, even in a private hospital.

In January, Kudakwashe Musasiwa, a 42-year-old founder of an online shopping enterprise, endured a week of pain, fever, three Covid-19 tests, two antigen tests and a chest X-ray before doctors treated him for Covid-19.

“Getting a hospital bed alone was a nightmare,” said Nomaliso Musasiwa, Musasiwa’s wife.

They called an ambulance, but it never came.

They also contacted the hospital where he was headed, but no one answered. “At this point using a car was hard since he was on an oxygen concentrator,” Nomaliso said.

Kudakwashe ended up in the hospital for 16 days. He couldn’t breathe and was in danger of dying. He got a ventilator with the help of friends and family. It took him weeks to recover.

Chanetsa has now fully recovered, but it took two or three weeks before he “felt close to normal,” he said. And he’s careful to protect himself against Covid-19 because “I won’t want to experience that kind of pain again.”

He doesn’t regret avoiding the hospital.

“I treated myself until I got better,” he said. — Global Press Journal