BY RONALD ZVENDIYA

A

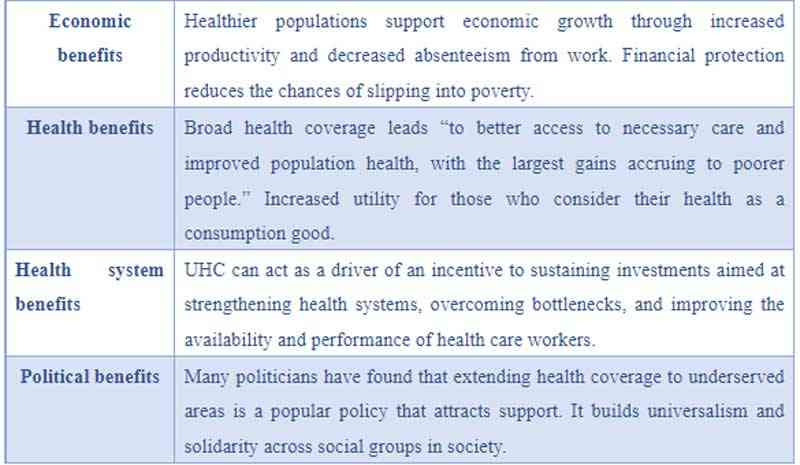

ccording to World Health Organisation (2010), Universal Health Coverage (UHC) means that all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.

This definition of UHC embodies (1) equity in access to health services — everyone who needs services should get them, not only those who can pay for them; (2) the quality of health services should be good enough to improve the health of those receiving services; and (3) people should be protected against financial-risk, ensuring that the cost of using services does not put people at risk of financial harm.

On 12 December 2012, the United Nations General Assembly endorsed a resolution on Global Health and Foreign Policy urging countries to accelerate progress toward universal health coverage (UHC) — the idea was that everyone everywhere should have access to quality, affordable health care as an essential priority for international development.

Furthermore, on 25 September 2015, the resolution on Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted the target 3.8 of SDG 3 for achieving Universal Health Coverage by 2030, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

On December 12, 2017, United Nations passed a Global Health and Foreign Policy resolution that focuses on addressing the health of the most vulnerable for an inclusive society.

The resolution calls on the member states to promote and strengthen their dialogue with other stakeholders, including civil society, academia, and the private sector, to maximise their engagement and contribution to the implementation of health goals and targets through an inter-sectoral and multi-stakeholder approach.

- New Horizon: Hare and baboon: The case of gold coins in Zim

- New perspectives: What Zimbabwe needs to achieve work for all

- New perspectives: Relevance of pensions dashboard architecture

- New perspectives: Why Zanu PF is not so successful after 2001

Keep Reading

Key capacity challenges

Service delivery capacity has expanded, but not sufficient to meet current and future needs. Health professionals are the most critical input in the delivery of health services.

The shortage of skilled health workers has been a consistent bottleneck to achieving UHC across the continent and is particularly severe in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Access to safe, affordable, and quality essential medicines remains a challenge.

Common challenges include high prices, inadequate financing, weak pharmaceutical regulation, and inadequate procurement and supply systems. Africa has an increasing circulation of counterfeit and sub-standard medical products due to the weak performance of national regulatory authorities.

Out-of-pocket spending on healthcare by households remains high. The need to strengthen domestic mechanisms for prepaid funding remains a priority for health systems. The role of insurance coverage is critical since social health insurance and other forms of insurance are low.

The risk to the human security of not having sufficient capacity to respond to pandemics has become paramount. There is a need for training in epidemic management in all countries since almost every new type of disease arises periodically.

Lessons from other countries

Lesson 1: UHC is a political process and commitment from the start.

The critical factor that leads to the successful implementation of a policy is genuine and sustained political leadership — often at the head-of-state level. Across different regions, political leaders have recognized that by bringing accessible health care to the masses, successful UHC reforms are extremely popular and can be a potent political tool to help win and sustain power.

Lesson 2: Engage the private sector to support UHC

Across Africa, private health providers deliver the majority of outpatient health services. The challenge for countries moving towards UHC is to find ways to engage the private sector as a way of maximizing access to health services. However, there is much more scope to deliver services through a mixture of public and private providers.

Lesson 3: Closing primary health care gaps is a foundation for UHC

Countries wishing to make rapid progress towards UHC should prioritise primary health care. Well-structured, efficient primary health services can meet most of the health needs of the population. Without a comprehensive primary health care approach through which proven, cost-effective and life-saving services can be made available to all, countries will be unable to ensure that services promised by UHC commitments are accessible to citizens.

Lesson 4: Commit more public financing to UHC.

Build and sustain an adequate level of pooled public funds as the predominant financing mechanism for the health system through:

Incremental growth in the allocation of GDP to health. Countries should aim to spend at least 3% of GDP on public expenditure on health and health care.

Increasing revenue from alternative sources (e.g. through additional taxes on some commodities such as alcohol, tobacco, sugar, etc. — the so-called ‘sin’ taxes)

Lesson 5: Align purchasing with benefits to turn promises into results

One particularly promising direction is to create an explicit link between purchasing mechanisms and declared benefits for the population. For example in Kyrgyzstan, when an ineffective fee exemption system was replaced in 2001 by a mechanism to pay providers more to treat people in exempt categories, there was a dramatic decline in out-of-pocket payments by people in exempt groups

Universal health coverage related capacity issues

Monitoring and evaluation Health sector professionals need to know how to track and analyze the evidence needed to monitor equity. They must also be adept at designing and adapting survey instruments and other means of collecting evidence.

Availability of human capital

The health sector critically needs people with the capacity to generate country-specific evidence on the feasibility, sustainability, and equity of different financing sources.

Implementation capacity

In Zimbabwe, the problem is not policy but implementation capacity. For UHC to bring about desired outcomes, countries should be helped to strengthen their ‘how’ to do things practically.

Convening, negotiating and consensus-building capacities are needed to harmonize benefit packages and payment methods and to minimize gaps across schemes.

In conclusion, the UHC journey for each country is different so there is no one size fits all blueprint. Every country can make progress from its current position. All countries, regardless of their economic status, can increase domestic revenue for health by improving tax collection and curbing illicit financial flows. Countries should draw on lessons from best practices to shape their journeys, making adjustments and adaptations as they build experience. The groundwork for UHC needs to be laid carefully so that service provision can meet health needs irrespective of where the funding comes from. Financial protection through health insurance is the way to go if UHC is to yield results.

Zvendiya is a research and innovation analyst at the Insurance and Pensions Commissions (IPEC) who writes in his personal capacity. Contact details: [email protected],

*These weekly articles are coordinated by Lovemore Kadenge, an independent consultant, past president of the Zimbabwe Economics Society and past president of the Chartered Governance & Accountancy Institute in Zimbabwe. Email - [email protected] and mobile No.+263 772 382 852.