On November 24, 2022, Finance minister Mthuli Ncube tabled a $4.5 trillion budget wherein the ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) was allocated $631.3 billion or 14% of the total budget (US$6.85 billion using the official exchange rate of the budget day).

Although this is an increase from the 12% allocated in the 2022 national budget, a staggering 87% of the allocation is going to employment costs.

For the infant education programme, a whopping 93% will go towards employment costs despite the glaring need for infrastructure and learning materials for early childhood development (ECD) learners.

Retrospectively, up to September 2022, employment costs accounted for 94% of total actual expenditures in the MoPSE.

The 2023 budget estimates that there are 135 685 government employees in the education sector in Zimbabwe, 83 730( 62%) females and 51 955 males.

Despite the seemingly huge expense on salaries, parents still pay for extra lessons.

Although government has made it clear that such practise is illegal, parents cannot report the errant teachers as this is tantamount to creating a wedge between the teacher and the student.

Moreover, there are reports of a close syndicate to fleece parents involving the class teacher, headmaster and the schools inspectors.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The erratic releases of budgeted funds is a cause for concern as this negatively affects the ability of the Ministry to meet its mandate as espoused in the National Development Strategy (NDS1).

The 2023 budget shows that only 52.7% of the 2022 MoPSE budget had been released by 30 September 2022.

This has been the trend for the past three years and casts aspersions on the credibility of the budget and the processes.

The tuition grant of $1.3 billion proposed in the 2023 budget is grossly insufficient to improve access to learning opportunities and reduction of inequalities.

As such, the portfolio committee on education chaired by Torerai Ngidi Moyo has rightfully advocated for the creation of a special fund for tuition financing.

Such a fund, while not a guarantee of equality in education, can bring significant benefits for children especially girls who are often disadvantaged when families fail to raise enough funding for children’s education.

Call it ambitious, the government of Zimbabwe has committed to provide free basic education starting 2023.

The absence of a funding mechanism for free basic education, however, implies that parental contribution will remain high.

Children from poorer families will still face the risk of dropping out of school and the girl child is at the greatest risk.

Government has, however, directed that no learner can be expelled from school on the basis of non-payment of fees.

This directive has largely been ignored as schools still expel students, even on the opening day for non–payment of fees.

The way this directive has been relayed has given the impression that parents should not meet their obligations.

As such, most schools are struggling while they sit on huge piles of receivables, some of which should just be written off as some of the non-compliant kids have advanced to the next level of education or have changed schools.

To enhance inclusivity and equality in education, government created the Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) programme in 2001 to ensure children from marginalised and vulnerable families have access to education.

BEAM, ideally, should provide school fees, examination fees, levies and uniforms to vulnerable students between six and 19 years.

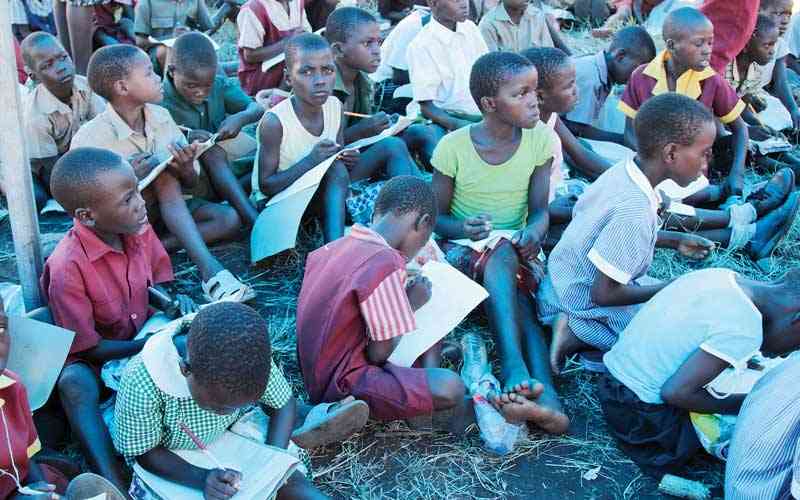

A 2017 education report found that at least 63% of children were unable to pay for their schooling and the schools subsequently sent them home.

The BEAM programme is, therefore, the answer for their predicament.

The 2023 budget proposes to cover at least 1.5 million learners from vulnerable households with a proposed allocation of $23 billion for BEAM.

Fund management concerns, accounting and governance issues as well as coordination between the two ministries of Education and Social Welfare have, however, stained the programme since its inception.

Most of the schools are reeling from non-disbursement of funds and are therefore supporting the teaching and learning materials of children under BEAM with fees from paying parents. It has also been noted that some undeserving students are on BEAM beneficiaries lists which points to corruption in the selection criteria for BEAM beneficiaries.

Besides being insufficient to match the needs of all orphans and vulnerable children , BEAM is marred by inadequate releases.

Only $4.1 billion of the $20.5 billion 2022 BEAM budget was released, translating to a mere 20.3%.

This covers only tuition and leaves the OVC to cover their examination fees, uniforms and learning materials.

Meanwhile, government is also financing the poor and vulnerable children in P3 and S3 schools under the tuition-in-aid grants within the MoPSE budget.

Harmonising the two financing modalities has been recommended by stakeholders so as to reduce administrative costs, and improve targeting.

Access, equity and inclusivity of education is also enhanced through the Leaner Support services programme in the MoPSE.

This programme was allocated $24.2 billion, which represents 3% of the total MoPSE budget in 2023.

Out of that, $ 2.8 billion is for the home-grown school-feeding programme targeting 6400 schools.

Per capita allocation is therefore $437 500 per school.

School-feeding programme was allocated $2.29 billion in 2022 and had only utilised 3.6% of that by September 30,2022. In 2021, the programme utilised 9% up to same period.

The promulgation of the Education Amendment Act in 2020 has strengthened the legislative framework and opened vast opportunities for advancing the interests of the girl child, including Sexual and reproductive (SRHR) issues in the budget. Section 4 (1) of the Act states that “The State shall ensure the provision of sanitary ware and other menstrual health facilities to girls in all schools to promote menstrual health.”

Sanitary wear was allocated $ 1.5 billion, up from $1.23 billion in 2022, targeting to increase the coverage of female learners receiving sanitary wear to 941853 in 2023 from 941 653 in 2022. 2021 EMIS report indicates that there are 549 691 girls in secondary schools.

Per capita allocation is therefore $2729 (US$4.20). As of September 30, 2022, utilisation was $263 million (21%), which shows same trend with the $74 233 508 (14.8%) utilised in the same corresponding period in 2021.

Historically, Zimbabwe created free and compulsory primary and secondary education in 1980, soon after attaining independence.

However, parents had to pay building levies as well as sports fees for buying equipment and material.

After the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme of 1992, government reduced its financing of social services and education ceased to be free.

In 2013, Zimbabwe adopted a new constitution that guarantees every child has a right to basic education.

Section 27 of the constitution of Zimbabwe provides that the state ‘must take all practical measures to promote free and compulsory basic education for children”.

The Act places the duty on the state to progressively fund basic education within the limits of resources available.

Section 75 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe states that, every citizen and permanent resident of Zimbabwe has a right to a basic state-funded education and further education, which the state through reasonable legislative and other measures must make progressively available and accessible.

The enactment of the Education Amendment Act in March 2020, laid the groundwork for guaranteeing free, publicly funded, inclusive and equitable primary and secondary education.

The Act also obligates the state to provide sanitary ware and other menstrual health facilities to girls in all schools to promote menstrual health.

The Act also precludes expulsion of students from school for non-payment of school fees or on the basis of pregnancy.

Given the limited public resources, the free basic education is expected to be gradually rolled out, beginning 2023, initially prioritising socio-economically disadvantaged schools and the most vulnerable.

The parliamentary portifolio committee on education has lamented the lack of a funding mechanism in the budget to guarantee state funded education.

While there is a draft school financing policy in the MOPSE, it does not yet provide for a specific fund towards basic state funded education.

A commitment toward promoting the implementation of the school financing policy to enable schools functionality through creation of a sustainable government-led funding strategy such as an education levy to ensure state funded education is thus a must.

Government has, however, has committed to develop a national education financing framework that operationalises this state funded education.

Zimbabwe can benchmark with the Ghana Education Trust Fund (funded by 2.5% of VAT collections), the Nigeria Tertiary Education Trust Fund (to which national companies pay 2% of assessable profits), the Brazilian Fund for Maintenance and Development of Basic Education (earmarking 15% of VAT revenues) and China’s Educational Surcharge levied on VAT at 3% of consumption.

*Pepukai Chivore* is an economist and an expert in public finance management based in Harare. He writes in his individual capacity and can be contacted on [email protected]

These weekly articles are coordinated by Lovemore Kadenge, an independent consultant, managing consultant of Zawale Consultants (Private) Limited, past president of the Zimbabwe Economics Society and past president of the Chartered Governance & Accountancy Institute in Zimbabwe. Email – [email protected] and Mobile No. +263 772 382 852