BY THANDO KHUMALO

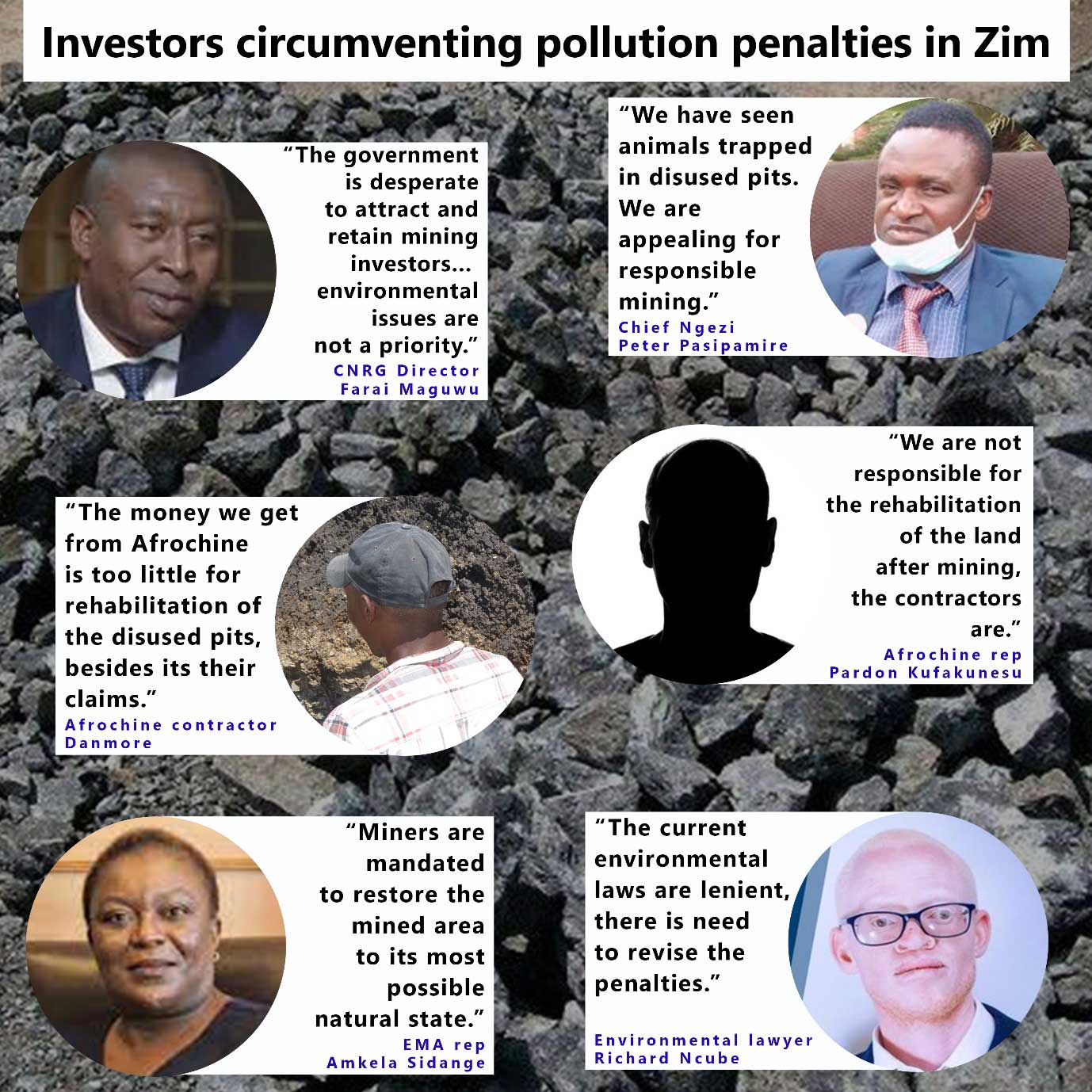

THE laxity in the enforcement of environmental laws in the extraction industry has left communities living in mineral-rich areas exposed to enormous environmental damage, threatening livelihoods as well as domestic animals, investigations have revealed.

With no financial support from multilateral creditors like the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the African Development Bank, analysts and conservationists say Zimbabwe, which badly needs investment to stimulate the economy that suffered two years of contraction has been left desperate for fresh capital.

As part of its investment drive, the southern African country has over the past decade been parcelling out chromite claims to indigenes and Chinese investors following the rise in global demand and market for chrome over the years.

Investigations by this publication in collaboration with the Information Development Trust (IDT) revealed non-compliance with the country’s environmental laws by Chinese chrome miner, Afrochine Smelting (Afrochine), which have left the communities in the mid-Great Dyke in Mashonaland West province, vulnerable.

These areas include Ngezi, Darwendale, Maryland and Lembe/Mapinga.

New information gathered by this publication revealed that government’s quest to achieve President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s dream of a US$12 billion mining economy by 2023 has left vulnerable communities at the mercy of giant mining firms that are abrogating the “polluter pays” principle — a commonly accepted practice that those who pollute should bear the costs of managing it to prevent damage to human health or the environment.

Small-scale chrome miners in the area accuse the Chinese-owned firm Afrochine of failing to rehabilitate the environment following mining activities, investigations reveal.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

A visit to the site revealed that both parties are negating their responsibility of reclaiming the environment with large disused pits, which the villagers say, are posing threats to their lives and livestock.

According to police reports in Darwendale, a minor drowned in one of the disused pits in December 2020 and livestock have been falling into the pits on a weekly basis.

Communities in the area have also expressed concern over the degradation of land by the foreign mining firm.

The environmental neglect

Companies in the extractive industry are guided by the Environmental Management Act (Chapter 20:27), which provides sustainable management of natural resources and protection of the environment, the prevention of pollution and environmental degradation, in mining.

According to the Act, “any person who causes pollution or environmental degradation shall meet the cost of remedying such pollution or environmental degradation and any resultant adverse health effects, as well as the cost of preventing, controlling or minimising further pollution, environmental damage or adverse health effects”.

Scores of small-scale miners operating on Afrochine claims insist that the rehabilitation of the environment after mining activities remains a responsibility of the chrome claim owner — Afrochine.

Despite this, Afrochine places the responsibility on the contractors.

“We are working on the Afrochine claims. We sell all our proceeds to them.

“Afrochine provides our blasting requirements, compressors, and de-watering pumps, if need be,” said Danmore, one of the small-scale chrome miners.

“In the case of any of the equipment developing a fault, or when perimeter fence collapse, who do you think should fix those things, it’s Afrochine.

“They own the claims, let them take care of the environmental degradation.

“After all, they are benefitting the most out of the mining activities done on the claims.”

However, Afrochine safety, health, environment and quality manager and public relations officer Pardon Kufakunesu said the miner who is registered to mine is supposed to rehabilitate the environment in accordance with certification papers from EMA.

“Afrochine Smelting has no chrome mines at the moment. It buys from other miners,” said Kufakunesu.

“Should the miners require assistance in acquisition of the certification from EMA the company is ready to assist in as much as they are also assisted in machinery and fuel requirements.

“We do, however, have our own claims. On these claims we give contracts to other miners to mine.

“But however, they follow the same process of acquiring the EMA certification and undertake environmental management in accordance with their mining activities,” he said.

According to media reports, government seized 77 chrome mining claims straddling over 2 000 hectares along the Great Dyke from locals and handed them over to Afrochine last year.

Accountability

The Environmental Management Agency (EMA) insisted that environmental accountability must take precedence for any mining activity to happen, but could not provide information into the indifference on the environmental rehabilitation standoff between the small-scale miners and Afrochine.

Section 269 of the Mines and Minerals Act states: “on or before the abandonment, forfeiture or cancellation of a registered mining location or not later than thirty days after the posting by the mining commissioner of the notice mentioned in section 272, the holder of such location shall fill in all shafts, open surface workings and excavations or otherwise so deal with them as permanently to ensure the safety of persons and stock”.

Simbarashe Machiridza, a legal expert, said according to legislation, in the event the claim holder fails to do what is set out in the Mines Act, he can be charged and face criminal sanctions including a fine or imprisonment for a period not exceeding one year.

He highlighted that the mining commissioner can also issue an order for the holder to perform his obligations to fill in pits as required by law within a specific time.

“If that order has not been complied with the holder can be charged with an offense and be ordered to pay a fine or be jailed for a period not exceeding two years.

“Legal remedies are there. The issue is whether there is adequate enforcement through the police or the mining commissioner,” Machiridza said.

Richard Ncube, an environmental lawyer said authorities should ensure the enforcement of laws while imposing stiff penalties that deter would-be offenders.

“The EMA Act is clear on what needs to be done in order to ensure that mineral host communities are protected.

“Communities have lost livestock and lives due to those dumps — they are simply death traps,” Ncube said.

“If there is no strong enforcement of the laws the law becomes redundant.

“There should be a functional rehabilitation or reclamation fund that helps in case of non-compliance.

“It makes economic sense for a company in Zimbabwe to pay fines than to cater for rehabilitation of the area.

“So, there is a need to revise the penalties.”

Desperation for investment

Farai Maguwu, a director at the Centre for Natural Resource Governance said because of poor enforcement of environmental regulations, most companies find it cost-effective to just abandon their mine dumps without following environmental regulations.

“Investors are well aware of the polluter pays principle, but it seems the Zimbabwe government is too desperate for attracting and retaining mining investors, hence environmental issues are not a priority,” Maguwu said.

“Because the government places mining above everything else, including the environment, polluters enjoy state protection and impunity.”

Maguwu said fines must be reviewed upwards so that companies won’t find it easier to pay fines than to comply with the regulations.

He highlighted that the current penalties were “not strong enough and deterrent”.

“There is no doubt that multinational and foreign companies understand the polluter pays principle, the major challenge is failure to respect the law in place,” Maguwu said.

“When companies get to a country, they are guided by the way of doing things in that country.

“As a country, we simply have to change our culture and how we treat mining companies.”

Other cases

Last month, three foreign-owned mines De-Troop Jiangxi Risheng, Morocco 7 Mine and Take 25 were fined for polluting the Angwa River, a major water source in Mashonaland West province according to EMA.

This followed compliance inspections that identified environmental violations in the handling of cyanide, discharge of mining effluent and the absence of spillage contingency strategies.

De-Troop, which is run by Chinese firm Jiangxi Risheng Mining Company, is situated along the Angwa River, about 170 kilometres north-west of Harare in Makonde district.

Apart from operating without an environmental impact assessment (EIA) certificate as required in terms of section 97 of the Environmental Management Act (Chapter 20:27), Morocco Mine was found in possession of 100kgs of cyanide.

According to EMA, Take 25 Mine had no valid EIA certificate and hazardous substances storage and use licence was ordered to submit a progress report on de-contamination and engagements with the local community.

Government is currently amending the Environmental Management Act to strengthen the regulations by providing for the comprehensive protection of the country’s environment in a manner that ensures sustainable development, Cabinet minutes reveal.

According to the minutes, the proposed amendments will see the imposition of deterrent penalties for non-compliance with orders issued by EMA officers or inspectors, including civil penalties in addition to the criminal sanctions.