Companies’ recruitment processes are mainly designed to enable the selection of the best applicant for a job based on objective and deemed fair criteria.

While the primary principle for selection is competence and suitability to the job requirements, the employers make reasonable efforts to achieve and maintain diversity and to some extent geographical balance of potential candidates.

On average the job seekers in Zimbabwe are coming from the universities, polytechnics, professional bodies and vocational training centres.

In this paper, I wear the lenses of the captains of industry and at the other hand am a product of the universities and these other various training institutions practising in our motherland.

The kind of candidates that the industry is currently receiving from these institutions of higher learning leave a lot to be desired.

Students will have submitted quite decorated curriculum vitae and or resumes but as you sit as a panel of interviewers to test the knowledge as marketed in the curricula vitae and resumes, these graduates are failing to perform.

They become so clueless to explain basic knowledge or principles. Something so terribly wrong I believe.

My main question is what has suddenly gone wrong with our tertiary institutions?

- Young entrepreneur dreams big

- Chibuku NeShamwari holds onto ethos of culture

- Health talk: Be wary of measles, its a deadly disease

- Macheso, Dhewa inspired me: Chinembiri

Keep Reading

Are these universities aware that within industry there is a debate that a student from so and so university is not an ideal candidate?

Do we have a genuine and effective university and industry collaboration that supports the academic season of these candidates? Is our education system useful to us as Zimbabweans?

Or rather, are our education systems educating the nation?

And on a much broader sense what are our milestones for our education systems towards the country’s vision of an upper middle income class by 2030?

With the influx of universities and polytechnics in Zimbabwe it is unbelievable that the country has a skills deficit of around 62%.

The engineering and technology sector has a deficit of around 96% (National Skills Audit Report quoted in the 2019 National budget statement).

It is sad reality that the Republic of Zimbabwe requires education that can produce graduates who can match today’s digital age needs.

That kind of education that is useful and can make a change in the new Covid-19 induced normal.

I challenge the universities that, the curriculum that worked in 1980 may no longer be effective in the 20th century, more so new living environment.

There is need for tailor-making the curriculum to match the needs and aspirations of the industry and commerce.

Universities and industries are key players towards our attainment of the upper middle income status target of 2030.

Therefore, the rationale of this article is to probe a roundtable between universities and captains of industry and be honest with one another on the expectations of each part.

I follow very well the government efforts through the line ministries responsible with education that our new focus as a country is towards education 5.0 (putting theory into practical action).

To me the respective ministers that I respect greatly have admitted that there is a serious gap between tertiary institutions and the industry, hence being pro-active.

Zimbabwe has a known record for producing very good blueprints, including this subject of discussion.

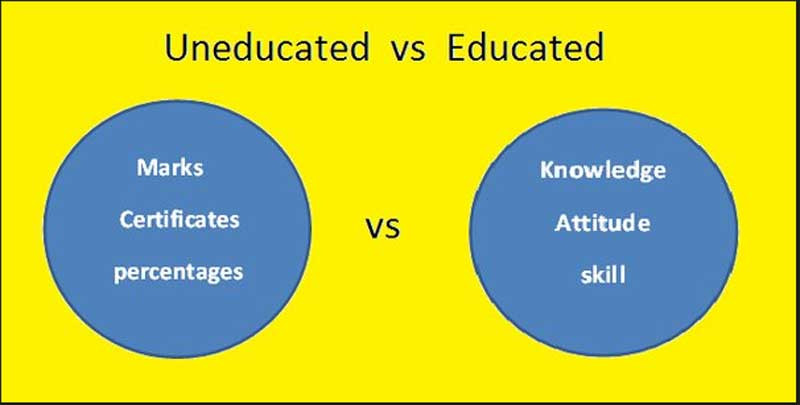

So where are universities going wrong to the extent of having students with higher certificates, but without knowledge and or skill?

Does that mean the students are reading for examinations and certificates without necessarily grasping the principles and ultimately knowledge?

In most colleges and universities, there are claims that the thrust and objective of the student is more inclined to graduating than to gain knowledge or skill.

Students seem to focus on passing the examination at almost any cost rather than grasping the concepts in the curriculum and have that hunger to go and practise.

Universities and colleges of modern day seem to be promoting the culture of studying selected topics only as students concentrate on areas they feel will be examined and ignore the rest of the issues.

In some instances, the lecturers encourage this kind of learning when they tell their class to be on the lookout for certain areas.

The lecturer puts emphasis on as grazing areas for end of semester examinations.

In such cases the students go through university or college only learning or cramming the little information narrowed down to pass examinations and not the concepts of the laid down curriculum.

My personal assumptions are as follows: currently there is no sound collaboration between the universities or tertiary institutions and industry. I seem to have realised that industry is quick to adopt to the technological changes and tertiary institutions are taking time to revise their curriculum to suit the ever changing times in technology.

One interesting aspect believe me you is; the course outline that was used for us the students of the 1990s is still the same with the current students.

That is a reflection that tertiary institutions are well behind the technological changes in industry.

If there was clear platform for that collaboration, tertiary institutions would have received this as key feedback.

I, therefore, suggest enhancing university/industry collaboration on product and service development to ensure that our students, after graduation, fit perfectly in industry with expected knowledge. A framework for the tertiary institutions and industry may be the best to codify the relationship.

The second aspect is much as the tertiary institutions curricula have the provisions of on the job learning or internship, the universities are not visiting institutions to assess if students are in correct environment that promotes learning.

Most organisations are seeing cheap extra hands in these student interns if tertiary institutions do not make follow -up engagements. Relying on the student attachment report alone is not enough.

There is great need of engagement between tertiary institutions and industry and come up with a collaborative assessment tool of students on attachment. Ideally, universities should accord former students or alumni as mentors of these students and entrust them with the assessment process.

This suggestion means universities should approve attachments where students must be tied to university alumni.

That way, students are nurtured within the expected university culture or flagship.

What is currently happening is the majority of these students are placed under mentorship of people who do not understand the respective university culture or do not even have a first degree and that one year of attachment ends up as a wasted year in terms of skills acquisition.

Thirdly, there is need for the tertiary institutions to have a platform to examine the final students if they still grasp the knowledge of perhaps first year modules that cover the principles of each and every profession.

The examination could be like a skilled test of the trade. This will assist in making sure students continue to relate to the principles and apply them within the practical expectations.

Fourthly, the lack of compliance monitoring for specialisation of colleges and universities and separation of training from education has led to widespread condemnation of vocational skills.

Failure to recognise the intellectual and economic contribution that such skills have to the industry and commerce is costing the Zimbabwe millions of economic growth potential.

Of late, we have seen polytechnic colleges applying to offer degree programmes and the labelling of polytechnic college graduates as lesser intellectuals although industry has noted that it is the same polytechnic colleges that used to provide much of their skilled manpower through the apprenticeship collaborative programmes, to mention but a few.

We have also seen some universities diverting from their core thrust, for example, those meant for science education, technology or entrepreneurship now offering social sciences or commerce degrees.

Universities and colleges must be encouraged to concentrate on the curriculum of their mandate. That way we may reduce the skills gap..

In conclusion, the article is calling for the tertiary institutions and industry to have a collaborative effort to educate our youths for they are our legacy.

They must be equipped with the knowledge that helps improve our industry and commerce.

Teach them to be entrepreneurs not employees.

Our universities seem to be currently tailor-made to provide academic needs and requirements and as such it is logical for the academic universities to produce graduates who are of academic nature as this resonates well with the philosophy of their learning experience.

I, therefore, posit that Zimbabwe needs to make a paradigm shift and put in place some accountability framework to our universities, polytechnics and vocational training institutions’ curricula that provide students with both academic and hands-on skills that make a difference in our modern industry.

Academic means relating to education and scholarship, not of practical relevance but of only theoretical interest.

Universities are designed to provide academic needs and requirements and as such it is logical for the academic universities to produce graduates who are of academic in nature as this is in line with the philosophy of their learning experience.

Polytechnics and vocational training centres must focus on the practical side of education. Zimbabwe needs to come up with a system that puts in place new curricula that provides the student with both academic and skills experience.

The Zimbabwean education system must benefit the nation and as such the universities and colleges curricula must reflect on the ethics and demands of our industry and economic needs.

In this new normal, innovation is the cutting edge difference between growing economies and shrinking economies.

A robust education system that equips the learner with skills to perfectly fit in the industry and commerce is the only way of ensuring that the Zimbabwean economy breathes life again.

Langton Mutoya isan academic and personal assessment writing in his personal capacity. Email: [email protected]

Mobile: +263772 702 361