By Fred Zindi

With the collapse of record shops and increase in piracy, many artistes in Zimbabwe are now dependent on streaming and YouTube to earn royalties from their recordings. A lot of you are wondering how big African artistes such as Nigeria’s Burna Boy have become millionaires in this fast-changing digital world.

There are hundreds of artistes who sweat hard to record their compositions after weeks of rehearsals, but at the end of the day receive no income from their efforts.

One artiste from Mbare, Harare,declared: “I don’t care whether I make money from CD sales. Sometimes I even give my CDs free of charge to the public so that they get to know my music. That way, if I decide to have a concert, they will all flock to my show because they will know what music to expect from me.”

There are a few more artistes with the same attitude towards their business that it becomes difficult to monitor how recording artistes get paid for their efforts.

With the growth in streaming and online services such as Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, YouTube, Itunes and several others who are at war with each other, artistes who have registered with these, get some kind of royalties butthe extent to which these royalties reach the artiste is debatable.

In Africa, for instance, if one is interested in a song and wants to buy it on-line, it becomes a big problem. One needs a computer, an Ipad or a mobile phone. They also need data bundles and a bank card to make the purchase. If someone in rural Zimbabwe who has never seen a bank in his life or lives very far away from a bank wants to buy the song on-line, how would he or she go about it? In the past, that customer would simply go to a nearby record shop and do a direct purchase using cash, but all that has been changed by modern technology.

However, there are millions of people in Africa today who are more likely to have a mobile phone than a bank account. The question is, how can recording artistes harness this situation to make more record sales through the use of mobile phones?

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Most artistes have no idea how to go about using the digital platform to market themselves. Some do not even have the resources to know where to start. But the need to learn how to do so is more urgent than ever before. There are artistes who think that putting their music on YouTube will automatically give them cheques once they have enough ‘likes’ to their music. It is more complicated than that.

It’s an awkward phenomenon that now pervades a growing cross-section of industries, a type of techno-solutionism that’s unbearable because it insistently capitalises on quick fixes for problems that didn’t exist before.

The music world continues to be exceedingly vulnerable, and there are looming questions that desperately need to be addressed. Most important: Seeing that record shops (where artistes used to be focused on placing their products in the brick-and-mortar stores), don’t exist anymore, how can artistes distribute and sell their work in a digital economy beholden to ruthlessly commercial and centralised interests?

Most of us have access to our phones, but not bank accounts. Purchasing music through the use of services such as Ecocash in the same way this service is used in supermarkets and on the streets, would help a lot of artistes.

There are challenges involved in trying to access a bank card.

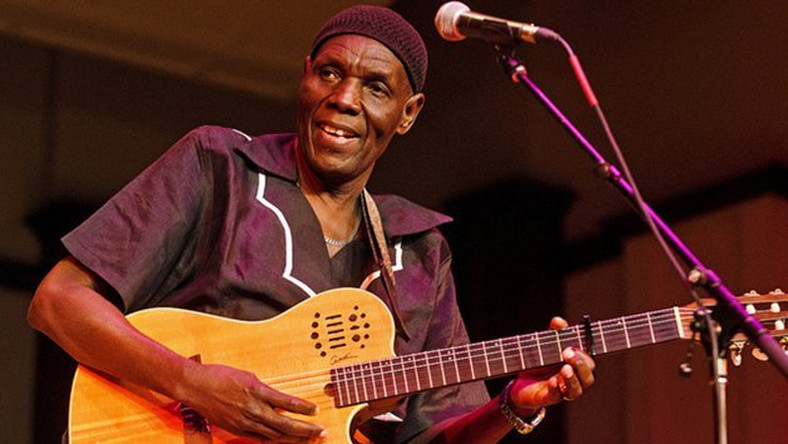

Costs associated with opening bank accounts, the distance to financial institutions and the difficulty in meeting Know Your Customers requirements where banks demand identity cards, passport size photographs and proof of residence, making it hard for people in rented accommodation or unemployed to apply, have added to the appeal of using phones to pay. To make matters worse, it is also becoming the operating motive of the music industry. Gogo in the rural areas wants to buy her favourite Oliver Mtukudzi record. She must have a cellphone or an iPad and know how to operate it in order to pay for and download the music. Do you think that if she doesn’t know, she will bother? Ridiculous, but this is what the digital age is all about.

The past few years have seen an emphasis on shifting towards expansion of innovative banking services through mobile technology to capture lower income segments and the unbanked.

Three years ago, Pearson Pfavayi, a Zimbabwean entrepreneur of Oyo’s music entered into a partnership with Star FM and signed up many artistes with a view to digitally distributing their music through online platforms.

Before that, another organisation, Jive Zimbabwe founded by Benjamin Nyandoro, had also created an online platform for music distribution.

The platforms these players created in the Zimbabwe music industry are meant to combat piracy and make musicians benefit from their own products. But are these platforms they created easily accessible to their fans and customers? If they were, Pfavayi and Nyandoro would be millionnaires by now because the bottom line behind this creation is to make profitable business.

These platforms have manipulated the vast majority of music industry “players” into regarding it as a saving grace. I am yet to get figures from them on the amount of royalties paid to individual artistes in order to verify if their businesses are doing well.

Gone are the days when Record and Tape Promotions (RTP) Gramma Records and Zimbabwe Music Corporation (ZMC) would distribute large sums of money in royalties, which would enable up-coming musicians to buy houses within a year. Music fans would simply walk into a record shop and buy a record of their choice. There were no mobile phones or digital platforms which required consumers to pay for wi-fi and download their chosen songs. It was easy. I am not sure why the record shops have disappeared, but with the economy of Zimbabwe being on a downward trend, unemployment and hardships included, the closing down of such ‘luxury’ businesses is understandable.

The Zimbabwean online platforms are not alone in this game. As far back as 10 years ago, Apple’s iTunes and Amazon were already exploiting the mobile platforms internationally. Today, other players include Sound Cloud, Audiomack Band Camp, Vimeo and Tidal.

For Apple Music, the bottom line is selling iPhones, laptops, iPads, and other hardware created by the same company. Streaming music makes those products more valuable. One cannot download the music without these gadgets. Billions of dollars are made this way. For Amazon Music, the motive is similar; they aim to sell Alexa devices and Amazon Prime subscriptions.

Enter Spotify. As of September 2020, Spotify which also distributes music on-line, has been valued at US$20 billion by venture capitalists who see it as the next Netflix.

Yet, despite its conventional market viability, there are key differences between Spotify and its rivals, Apple Music, Amazon Music and the rest. Spotify’s worth is more ephemeral. Its value — what makes it addictive for listeners, a necessity for artistes, and a worthwhile investment for venture capitalists — lies in its algorithmic music discovery “products” and its ability to make the entire music industry conform to the new standards it sets.

I have no qualms with this kind of marketing. My only bone of contention is how the musician will benefit from all this especially if they have no knowledge of how it all works. Some of these companies massively underpay the creators, and just kick back and put their feet up, knowing that if TockyVybes, Rocky, Nutty O or Enzo Ishall doesn’t like it, well that’s fine, because there are thousands of other musicians lined up behind TockyVybes, Rocky, Nutty O or Enzo IShall who are perfectly happy to volunteer their music to exactly such a scheme in hopes of doing something greater than being a CD vendor in Mbare their whole life.

I want to believe that it’s not too late to beat the greedy sharks. To give you an example of how music makes money, according to the New York Times, Spotify has just signed a lease for 14 floors at Four World Trade Centre in New York. The company has gone on to hire an additional one thousand employees. The new lease costs US$2,77 million in monthly rentals. And it lasts until 2034.

Zimbabwe could also look at how to digitally enhance the marketing of its music products.

Africa, with its internationally recognised musical talent – and growing mobile phone use – is central to Spotify’s plans to extend its reach to a billion customers. How the profits made will be distributed to the artistes, who are the creators of such music, is a question we will need answers for.

- Feedback: [email protected]