Prominent environmentalist Yemi Katerere says Zimbabwe is losing a lot of forests and if the rate continues people will struggle to sustain their lifestyles.

Katerere (YK) told Alpha Media Holdings chairman Trevor Ncube (TN) on the platform In Conversation with Trevor that Zimbabweans “cannot just continue to live as if everything is available for everybody at the quantities that they want and to use the environment in any way and manner that they would like to do.”

Below are excerpts from the interview.

TN: Dr. Yemi Katerere, welcome to In Conversation With Trevor. YK: Trevor, thank you so much for inviting me to join you in conversation with Trevor. It is an absolute pleasure and I am looking forward to the discussions.

TN: Yemi, doing my research on you I was like, where am I going to start?

- You have been all over the place in terms of the field you are in, across the world and across the globe.

- I am struck by the fact that you have 30 years experience in commercial forestry, research, development, policy related stuff at non-governmental organisation (NGO) level and state level.

- If I was to say to you what have been the highlights of those 30 years in this great space that you are in?

YK: I think I have been privileged really to be able to work with the state, and I think that working with the state brings a lot of advantages, because when you work in the environmental sector the state is a key actor.

Also, there is an interaction between the state as well as civil society organisations, communities and so forth in terms of their lives and their economies are directly dependent on nature.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

So you cannot avoid that.

Often the relationship between nature and people is about policy, because that is what you are looking at because people impact nature and also nature impacts their lives and livelihoods.

So you begin to interact.

I interact with the NGO community, local communities, the state and of course the private sector which is a key player in terms of many industries although they may not realise that their businesses rely on natural resources.

So whether you are talking about water, if you are brewing beer you need water and if those rivers dry up your business is at risk.

In the private sector you have to think what the risks of depleting nature and biodiversity are.

One of the things that I have always felt Trevor, is if you are going to work in this sector you also need to stay abreast of the research and the developments and the thinking and the debates that are taking place.

One way of doing that is engaging with research, attending seminars, and publishing because that is where you tend to stay abreast of the developments and what is going on.

I have worked in the NGO sector, I have worked in the state sector, I have been on private sector boards and I have been an international civil servant with the United Nations, so I have had an enriching career.

TN: An enriching career in a space Yemi where this is big stuff.

- The environment. Forestry. And you are dealing with civil society?

- You are dealing with governments, policy formation. It is one of those places you might be forgiven for thinking that nothing is actually happening.

- I drove around the streets of Harare or flying all over the world and there is a temptation to say but is what we are doing making a difference?

- Does that ever cross your mind? Are we making a difference?

YK: Well, let us say this; there are lots of people who are dedicated and committed to ensuring that the state of the environment is resilient.

That the integrity of our ecosystems, where we get a lot of services, whether it is clean water, whether it is soils for agriculture, that those things are taken care of.

There are people’s lives that are directly dependent on that.

If water disappears their lives are impacted quite significantly, so there are people working on these issues.

The question is: are we winning the battle?

We are losing a lot of biodiversity. We are losing a lot of forests. So clearly there is a challenge and that if we continue at this rate then we are going to reach a point where we cannot sustain the lifestyles that we are enjoying today and so it’s got to change.

So one of the underlying things is the issue of change that we have to embrace change, we cannot just continue to live our lives as if everything is available for everybody at the quantities that they want and to use the environment in any way and manner that they would like to do.

So there has to be something that begins to give.

We have to live within the limits of nature, and if we go beyond that then I think we will start to feel the stress.

TN: I hear you Yemi saying you know there are people dedicated to that?

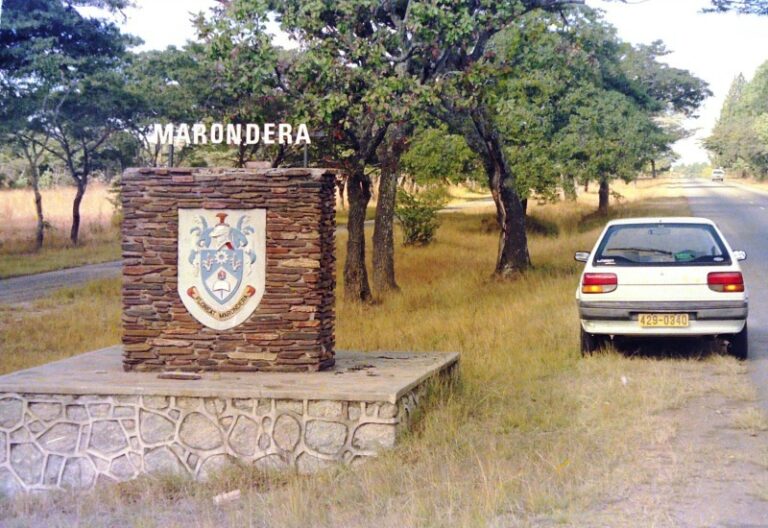

- I mean let us take for instance our Zimbabwean environment.

- Do you get the sense that we do appreciate the fact that there is a limit to which we can use the nature and environment we have, water, the way we treat the soil so forth.

- Do you get the sense that we are respectful of what we have been given by nature, by God? Have we gotten to that space?

YK: It depends where you are.

If you go to the local level, clearly those people understand more than anybody else what it means to respect nature, to use nature in a particular way, because they know that when that nature is gone…

It might be something as simple as energy, so if you are dependent on biomass, wood for cooking and there is no wood, you start to walk longer distances.

Water, the same thing, you start to walk longer distances to fetch water.

Same thing with soil productivity, if you are cropping and trying to grow some maize or groundnuts whatever the case might be, as the soils deplete you begin to see that your harvests are also depleting.

So at that level those people fully understand that, and sometimes we are not learning enough from these people that understand this relationship.

Even in the city, we might think that we have no connection with nature but we do.

So if you think about it: where does our food come from?

You and I go to the supermarket to buy. Where is that coming from?

It is being produced somewhere and it is being produced often in a rural setting on a farm or in the communal areas.

So sometimes we do not make that connection.

Or when we turn the water tap on we do not think where that water is coming from until it stops coming out and then we begin to wonder what is going on.

I think maybe we need to work more on the education, for people to be more aware of the centrality of nature to our lives and our economies.

That when we talk about economic growth, and we talk about Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and those kinds of issues, sometimes we can pursue growth for the sake of growth, and we can say we are growing at 10%.

What does it mean in reality?

TN: What is the cost of that growth? YK: Exactly. Look at tobacco. It is a ‘golden leaf’, but if we look at the cost. We have a large number of out-grower farmers, these are small-scale producers that are growing tobacco under contract. They rely on cutting indigenous woodland to cure the tobacco, but we do not factor that cost, but one day we will wake up and we do not have any woodland left. We say we are earning a billion dollars a year from tobacco, but…

TN: What’s the cost…? YK: I think that is one thing that we need to really start to think about. Even at the policy making level.

So they have started here, they have introduced a tobacco levy, and the money from that tobacco levy is supposed to go towards (conservation).

TN: Supposed to…Hahahaha YK: They are growing, eucalyptus, they are so many issues around that. Is it the right thing to be growing eucalyptus?

It is a introduced species, it uses a lot of water.

Are we growing this eucalyptus species in the right areas?

Or are we just introducing it wherever there is land without thinking through what are the consequences?

What are the implications on ground water supplies and so on and so on.

So I think those are the kinds of things, so there is no kind of simple or straight respected to these kinds of issues because they are complex.

TN: They are complex. They involve lots of stakeholders.

- I must say, before we move on Yemi, for me, take this as a pedestrian view.

- The pedestrian view on my side is I just do not get the sense that we are fully possessed by the reality that water is a finite resource and land is a finite resource.

- We do not make the connection between the issue of tobacco as you are saying and the impact that it is having on nature.

- I do not see the priority that civil society, the government and the private sector and the citizens are placing on the importance of that balance.

- Am I completely way off or you would share some of my concerns?

YK: I would share some of your concerns, and there might be some people that get it, but I think that by and large people are preoccupied with today’s existence.

Where do I get my next meal, where do I get some money and those kinds of issues.

They are not thinking about the longer term.

So someone else needs to think about that longer term, and that is partly the role of the state and I think also researchers.

We need to be looking at those issues, and we need to be writing about those issues.

We need to be communicating about the longer term consequences and implications of the decisions we are taking today.

So the short term reality is it there, and for many people that is their reality.

I need water today, I need wood today to cook my meal, so wherever I get it I am going to get it.

So I think when we start to talk about more inclusive growth, how do we address the issues of poverty, how do we address the issues of inequity?

I think that as long as we continue to pursue growth for the sake of growth then I think that these challenges will always be there.

So I think that for me the biggest issue is, how do we tackle the issue of getting growth that is more inclusive.

We do not leave people behind, and we can begin to tackle some of these issues.

So I think coming into the Forestry Commission it was a parastatal, but it was a parastatal that had the hallmark of a government department.

The logo was a map of Zimbabwe with an indigenous tree in the middle. It did not inspire excitement about this organisation.

Historically it had been established to support the private sector.

So if we look at some of the activities of the commercial plantations, you grow the trees, you do research and the benefits by and large were accruing to the private sector.

So the first thing that we did is to try to rethink that.

That just growing trees is not a very profitable thing, and the rate of return is not so great.

We might as well grow crops, we would make more money.

Also if you are going to make money and make a difference at the national level then we need to get closer to the customer.

We need to value add.

So we grow a tree, we value add and get as close to the customer as is possible.

- “In Conversation With Trevor” is a weekly show broadcast on YouTube.com//InConversationWithTrevor. Please get your free YouTube subscription to this channel. The conversations are sponsored by Nyaradzo Group.