The United Nations High-level Meeting (HLM) on HIV and Aids in mid-2021 marks 40 years since Aids was first reported. Attention falls squarely on the progress made so far and what must still be done to strengthen the response to HIV.

The UN HLM decides on the targets that will shape the next decade of the HIV response. Unavoidably, the impact of Covid-19 on the HIV response so far and to come is central to its discussions.

Four decades of responding to HIV demonstrate the importance of science. The Covid-19 pandemic is a stark reminder that following the science is an inherently political decision. The HIV response must seize the opportunity and capitalise on the political commitment towards public health generated by Covid-19.

Despite the advances and worldwide efforts over the past 40 years, around 37,6 million people are living with HIV and 1,5 million were newly infected and 690 000 died from Aids-related causes in 2020 alone.

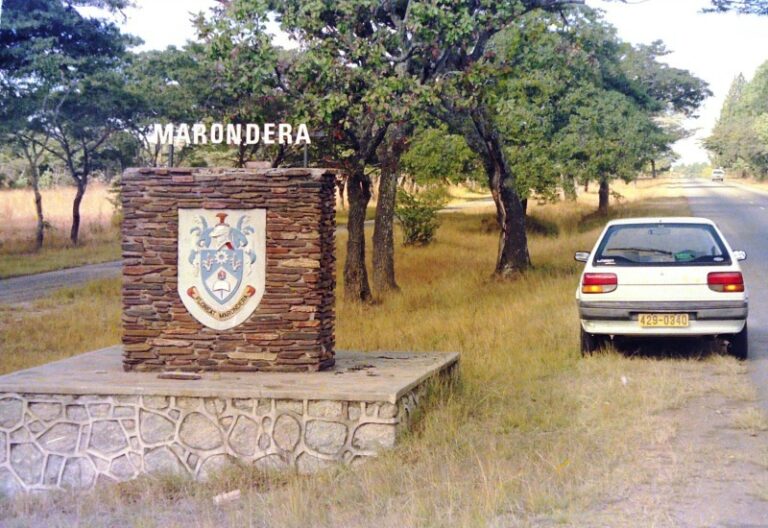

Only 10 countries, including Zimbabwe met the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets (that at least 73% of all people living with HIV are virally suppressed) by 2020. Tremendous progress has been made in developing effective treatments and prevention options, but we are still to develop a safe and effective HIV vaccine or cure.

In late 2019, a new pandemic, Covid-19, emerged. Disruption of essential health services during this pandemic is a global reality: 94% of countries reported disruptions in the first quarter of 2021.

Access to HIV prevention was reduced and there were decreases in testing and treatment initiation. Among Pepfar-supported programmes, voluntary medical male circumcisions reduced by 74% in April-June 2020 from the same quarter in 2019.

In South Africa, lockdown was associated with decreases of 48% in HIV testing and 46% in ART initiations in April 2020.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The impact of Covid-19 could be a tipping point for global health: an opportunity for improvement, innovation and investment in health systems or a risk of a colossal global scale if lessons are not learned for the future.

These include ensuring targeted, localised, context-specific responses that respect human rights and meaningfully engage communities.

An onslaught of misinformation has meant, in some cases, that the “defence of science” was needed to strengthen the connection between science and policy to ensure an evidence-informed response for both Covid-19 and HIV.

Varying national responses to Covid-19 are a reminder of the intersection and, often, tension between politics and following the science.

The Covid-19 pandemic has also driven an unprecedented level of personal and political will — and urgency — to protect public health. The immediate public health emergency and long-term disruptions to economies triggered a high level of public and private commitment and, crucially, funding.

This has helped drive logistical support and coordination and vaccine research and development unheard of in modern history.

Covid-19 has brought to the fore issues of health inequity and the importance of resilient health systems. It is essential to assess how some of the lessons learned from the Covid-19 response might strengthen pandemic preparedness and responses to infectious diseases in the future.

This includes harnessing digital technology and community partnerships in research and health service delivery.

Financial barriers and the influence of vested interests in intellectual property must be removed if we are to protect global public health.

As of March 2021, 78% of all Covid-19 vaccine doses had been administered in just 10 countries. Through the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, selected World Trade Organisation (WTO) members have been called upon to waive intellectual property rights that prevent lower-income countries from manufacturing the vaccine.

Although the first effective HIV treatment was discovered in 1996, it took years before low- and middle-income countries could access combination therapy. In that time, many lives were lost as ARVs were not available and prohibitively expensive to the majority of people living with HIV.

It took unprecedented community mobilisation, activism, global commitment, financing and political will, including the “3 by 5” initiative and subsequent 90-90-90 targets, to facilitate the rapid expansion of access to ART in resource-limited settings. We must not let history repeat itself and lose countless lives again due to inequitable access to scientifically proven and effective health interventions.

The coinciding of the WTO conversations with the HLM means that Member States’ interests relating to trade, intellectual property, access to Covid-19 vaccines and political priorities in the HIV response are inextricably linked. The denial of the basic human right to health in some countries poses the risk of failure in the responses to both HIV and Covid-19.

The “know your epidemic, know your response” approach remains crucial. Unless programmes are implemented within an implementation science framework and the impact of interventions are measured, we don’t know where to do more, scale up, develop further innovation or stop if an intervention does not work.

Science tells us that accessible HIV testing, with rapid linkage to care and treatment is vital in controlling the HIV pandemic and reducing AIDS-related deaths.

Globally, fewer than 60 countries were able to monitor all aspects of the 90-90-90 targets in 2019, with even fewer doing so among key populations — men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, sex workers and transgender people.

UNAids reports that only 47 countries can measure ART coverage among gay and bisexual men while 29 among people who inject drugs and 33 among prisoners.

This means that we don’t know how many people in key populations are unaware of their HIV status and if they need life-saving treatment or further support to attain viral suppression.

—International Aids Society