In his acceptance speech for a lifetime achievement award at the Golden Globes, on 10 January 2023, Eddie Murphy delivered simple advice for young creatives seeking to make their mark in the film industry.

Three things must be followed in the blueprint to achieve lasting success; “One, pay your taxes. Two mind your own business. Three, keep Will Smith’s wife’s name out of your f***ing mouth.” It is hard to talk about the most entertaining and striking comedians in the film industry without mentioning in bold the name Eddie Murphy.

Although Murphy’s advice was targeted at young creatives, the message should be a wake-up call to commercial actors and people that are flaunting excessive wealth on social media. Tax indeed is no laughing matter.

This might sound like a surprise coming from a comedian. However, there is nothing new here. When asked if it was lawful to pay tribute to Caesar, the Roman emperor, Christ’s response was precise: “Render to Caesar what belongs to Caesar.”

Against this backdrop, this article discusses the intertwined nature of tax and debt in Africa and illuminates the challenge of mismatch between natural resource wealth and deficiencies mobilizing tax revenue and how Africa can cross the line of sustainable development.

But what is tax, why is it so important? What is the return for paying taxes, and how does it connect with public debt, a pandemic that is burying Africa’s development aspirations?

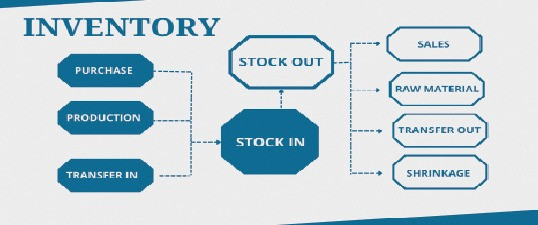

For governments to full fill their constitutional and political obligations, universal provision of essential public services and infrastructure — water, energy, transport, and communication — they must mobilise financial resources. There are various ways to raise funds. These encompass tax, debt, user fees, disposal of public assets, and official development assistance.

The principle of equity

- Open letter to President Mnangagwa

- Feature: ‘It’s worse right now than under Mugabe’: Sikhala pays the price of opposition in solitary cell

- Masvingo turns down fire tender deal

- Human-wildlife conflict drive African wild dogs to extinction

Keep Reading

Tax is the most substantial, accountable, and sustainable way for any government to raise revenue. Individuals and corporates are obliged to pay various forms of taxes, directly or indirectly. Direct taxes are deemed as very progressive as they are linked with the ability to pay by using income as the base for tax.

Put in other words, progressive taxation is based on the equity principle. The rich must contribute more taxes as a proportion of their income. The opposite is true for the poor. It follows then that from its natural wealth, especially finite resources, minerals, oil, and gas, more tax revenue should be mobilised.

If the government cannot raise sufficient taxes to cover its obligations, it may resort to borrowing to cover public expenditure — recurrent and public expenditures. When disaster strikes as in the case of Covid-19, governments borrow as a survival mechanism.

Borrowing can also be linked with huge public infrastructure investments which ordinarily cannot be financed by tax revenue in a short period. At an individual level, the salaries generally may not be enough to purchase a property. That’s why one may take a mortgage to buy a house for example. Governments can also borrow to pay debts — borrowing from Peter to pay Tom.

Debt must be repaid in the future, that is the principal amount and the interest portion known as the finance cost. Thus, the debt incurred today represents a future tax obligation.

Therefore, revenue raising is one of the most important aspects of taxation. Besides government borrowing to plug the gaps from failure to mobilise adequate tax revenue, more debt is likely to lead to more taxes. This is a nexus well expressed by Lyla Latif, February 2022; Is Africa’s fiscal space undermined by Debt related Illicit Financial Flows? A Case Study of Southern African Development Community (SADC) Member States. She elaborated that citizens in debt-distressed countries should fear increased taxation when their governments implement fiscal stimulus compared to low-debt countries.

Rich, yet poor

Despite Africa being endowed with vast natural resources, minerals, oil, and gas, poverty, and inequality are festering on the continent. Even with the seemingly promising prospect of the boom in demand for critical minerals required for the decarbonization of the economy and technological advancements, the picture is gloomy for Africa. Poverty levels are projected to rise, more so in resource-rich countries. Estimates from the World Bank show that by 2030, more than 80% of the world’s poor are predicted to live in Sub-Saharan Africa. Out of that, 75% will be from resource-rich countries.

As an illustration of how daunting the revenue mobilisation from mineral wealth is, in 2017, South Africa, with the world’s largest reserves of platinum, palladium, and manganese, mining, and quarrying, contributed 1.3% of total government revenue. It is a meagre contribution when compared to the 7.3% contribution of the mining sector to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in that year according to the World Bank’s Africa Resource Future Report 2023.

Conservative estimates reveal that Africa is losing US$88.6 billion annually through illicit financial flows (IFFs) according to the UN’s Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)’s Economic Development in Africa Report 2020. Nearly half of the losses are attributed to the mining, oil, and gas sectors.

The substantial part of the problem of the mismatch between natural resource wealth and the shortage of finance for development is not of Africa’s making. No excuses can be made for the high levels of corruption, political capture, and inefficient governance systems that characterise most resource-rich countries in Africa.

It still boggles the mind because the African countries have lacked the enthusiasm to adopt and implement the Africa Mining Vision (AMV) — a homegrown continental blueprint for harnessing mining for transformative and sustainable broad-based economic growth and socio-economic development. So far, Guinea, Mali, and Zambia are the only countries that have signed and ratified the African Mining Development Centre (AMDC) Statute. Notably, the AMDC is AU’s coordinating and technical support arm for the implementation of the AMV.

Tax dodgers

Looking at the big picture, African economies still mirror the colonial system of supplying low-value-added raw materials for the advancement of the Global North, while importing high-value-added finished goods. Africa’s struggles with value addition and beneficiation of its minerals and metals, and the capacity to mobilise additional tax revenue are exported along with jobs, downstream industries, foreign exchange, and income generation.

Multi-national Corporations (MNCs) have found it easier to dodge taxes in countries they have substantial economic activities by shifting profits to jurisdictions where lower or no taxes are paid because of the lopsided global financial and tax systems. Further, the tax system is designed to promote international tax competition, the lowering or waiver of taxes to attract capital at the detriment of domestic resource mobilisation. How ironic it is that the very countries that are bereft of resources to finance development are subsiding corporates through unnecessary tax incentives through engaging in a race to the bottom.

Redistribution of wealth is heavily compromised when public investment in health, education, and infrastructure is diverted towards the debt — the principal debt, interest, and payments. The UN’s Children’s Education Fund (UNICEF)’S 2019 report pointed out that 16 out of 25 very poor countries that are spending more on debt services than on education, health, and social protection combined are from Africa.

The need for global tax reform

African minerals that are deemed critical globally, especially by developed countries, may fail to matter to its people when it comes to fighting growing poverty and inequality on the continent. Although Africa has an important part to play in promoting good governance — doing the right thing, the right way, for the right people, in the right place, in a timely, open, inclusive, sustainable, and accountable way according to UK Audit commission 2009, the overhaul of the unjust global financial and tax systems cannot be overemphasized. The light at the end of the tunnel is showing from the adoption of the long overdue UN resolution for an inclusive and equitable global space for tax reforms.

Africa must revalue the motivation behind the Africa Mining Vision (AMV) and take from the additional impetus created by the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCTA) for sub-regional and continental solutions to value addition and beneficiation of its minerals. With greater retention of value on the continent, opportunities for revenue mobilisation are made wider.

Tax and debt are two sides of the same coin. There is no way Africa can extinguish its public debt crisis without ensuring that what belongs to Caesar should be given to Caesar. Of course, it is worth recalling loudly Eddie Murphy’s advice; Multi-national Corporations must pay an equitable share of taxes for the sustainability of their operations in Africa.

- Sibanda is a consultant with Tax Justice Network Africa as the focal point on tax and natural resource governance. He has a wealth of experience pushing for open and accountable management of mineral resources, which includes a widely-read blog on mineral-resource governance issues in Africa.