Zimbabwe’s latest proposed constitutional amendments have reopened a familiar and troubling pattern, the steady erosion of a document that was meant to be the country’s enduring democratic anchor.

Barely a decade after its adoption, the 2013 Constitution risks sliding into the same cycle that defined the Lancaster House era, a supreme law steadily chipped away through amendments until it becomes a convenient political instrument rather than a durable national covenant.

These proposed changes are not cosmetic adjustments. They strike at the very architecture of governance, altering the method of electing the President, extending terms of office from five to seven years, restructuring electoral institutions and abolishing an independent commission created to safeguard the rights of women.

Such structural revisions would ordinarily require broad national consensus secured through a referendum, not routine legislative manoeuvring.

Which raises a fundamental question: what, then, was the purpose of the 2013 referendum?

Zimbabweans did not casually adopt their current Constitution. The process was long, politically sensitive and financially costly.

Initiated under the Global Political Agreement, it involved years of outreach meetings, nationwide public consultations, complex negotiations among rival political parties, and sustained engagement with civil society, churches, labour groups and business organisations.

Millions of dollars were invested in crafting what was presented as a people-driven charter, a new social contract meant to stabilise governance after years of political turbulence.

- ED heads for Marange

- ‘Zimbos dreading 2023 elections’

- Your Excellency, the buck stops with you

- ED’s influence will take generations to erase

Keep Reading

Funded through a combination of government resources and donor support, the referendum process alone reportedly cost more than US$250 million.

When citizens overwhelmingly endorsed the Constitution in March 2013, they did so with the expectation that it would serve as a durable framework capable of guiding the nation across administrations.

A constitution is not meant to function like an ordinary statute, easily revised to suit the preferences of those in power. It exists precisely to restrain power.

The United States Constitution, enacted in 1787 and in force since 1789, has been amended only 27 times in more than two centuries, with the most recent change ratified in 1992.

Spain’s 1978 Constitution has been amended only three times, in 1992, 2011 and 2024. Many established democracies have preserved remarkable stability in their founding documents, precisely because the amendment process demands broad national consensus rather than partisan convenience.

Zimbabwe, by contrast, appears to be drifting towards a constitutional culture in which amendments become routine instruments of governance.

The Lancaster House Constitution was amended 19 times between independence in 1980 and 2009.

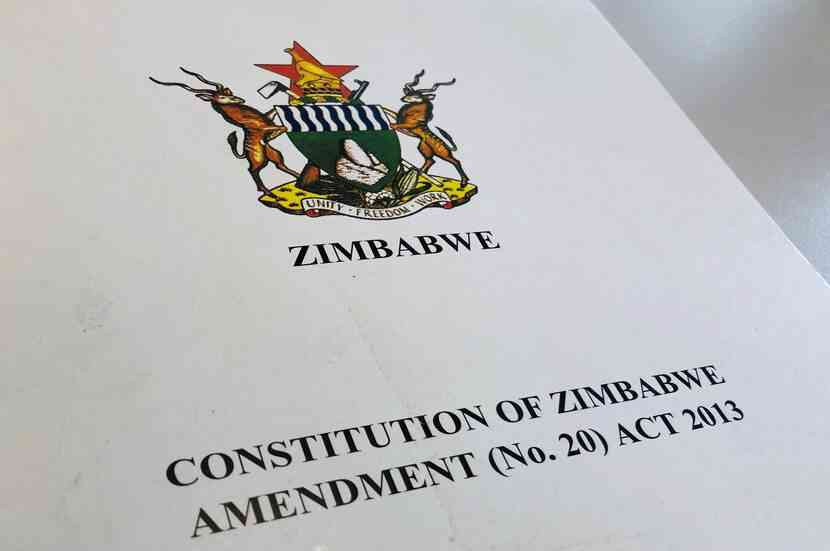

The Constitutional Amendment (No.20) Act of 2013, enacted on May 22, 2013, repealed the 1979 Lancaster House framework and introduced the current supreme law.

Each amendment may be justified individually, but collectively they risk hollowing out the principle that the constitution stands above politics.

There is also a deeper institutional danger. Once constitutional amendments become a regular feature of political life, future administrations may feel entitled to rewrite the rules to entrench their own advantage.

The threat is not merely legal, it is democratic. A constitution that shifts with political cycles loses its legitimacy as a neutral arbiter of power.

As the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights once warned, rather than strengthening the Constitution as a living document that protects rights, promotes freedoms and advances social and economic empowerment, repeated amendments risk becoming a routine mechanism for maintaining the status quo through political patronage.

Equally troubling is the message sent to citizens. The 2013 constitutional process was framed as a participatory national exercise reflecting the collective voice of Zimbabweans.

Incremental amendments through parliamentary processes that lack comparable public scrutiny risk diluting that original mandate.

None of this suggests that constitutions must remain frozen in time.

Societies evolve and reform is sometimes necessary. But amendments should remain exceptional, driven by overwhelming national consensus rather than narrow political calculation.

The more frequently the supreme law is altered, the more it begins to resemble an ordinary political document, subject to the shifting interests of those in office rather than anchored in enduring national values.