WHEN climate change is being represented in terms of its multiple shocks and negative impacts on the environment, least is foregrounded on how it contributes to poverty as the underlying factor. Although poverty is highlighted in terms of inadequacies of human well-being, the actual direct and obtaining link between climate change and poverty is sometimes implied rather than properly represented.

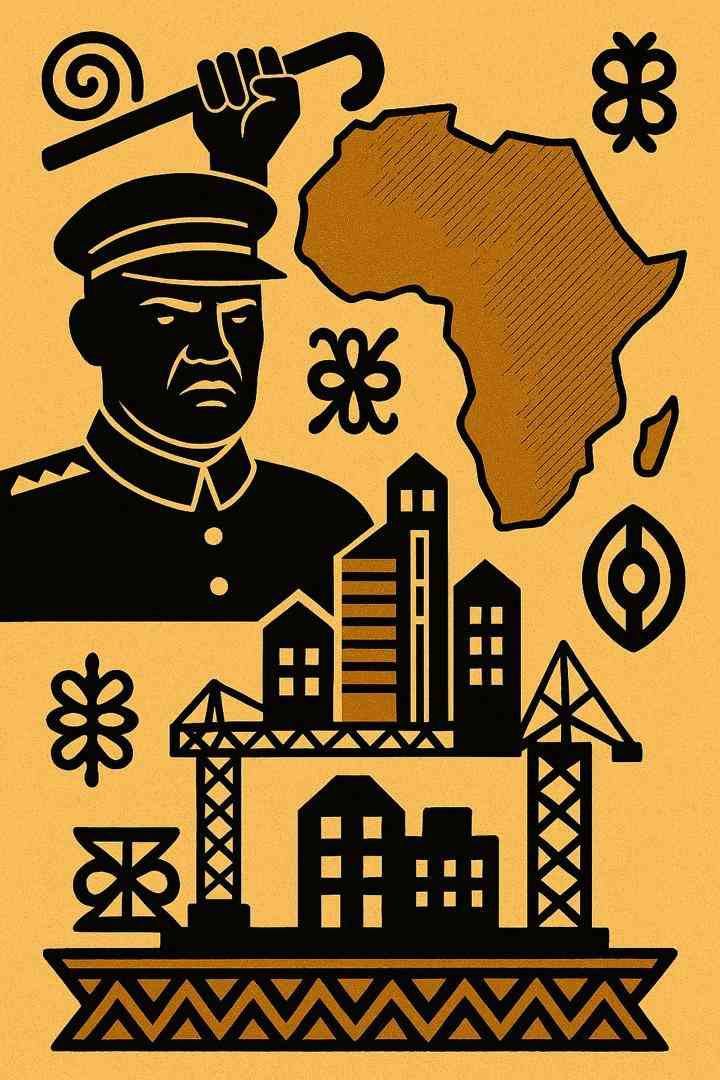

When climate change is talked about with Africa as a reference point and setting, only the causes and such issues as natural disasters, hazards and risks dominate the discourse. For this reason, stakeholders’ attention is deliberately diverted to negative impacts of climate change as the means rather than the end product, which is poverty. How poverty manifests itself as the deciding factor of negative climate impacts should be at the centre of any deliberation on sustainability issues. Poverty should not be discussed as the symptom, but as an undesired outcome of climate wrongs and environmental ills.

In the thick of things are reduced precipitations, water scarcities and stresses, droughts, flooding, deforestation, forest fires, cyclones, landslides, extreme weather events as agents of climate change, all leading to severe losses and damage to livelihood options. These are better pronounced and given due attention and publicity than human beings’ food insecurity, suffering and overall lack of coping mechanisms, regularly described as vulnerabilities rather than poverty.

The people at the epicentre of negative impacts of climate, need to be able to connect these impacts to loss of livelihoods leading to poverty. This direct link which would sufficiently reduce knowledge and information gaps on poverty is missing. People need to know how human activities are a case in point in terms of accelerating climate change. There is a thin line that climate experts and stakeholders sometimes fail to visualise, leaving out critical information, structural and procedural gaps. Therefore, the term climate change and its resultant impacts has overtaken the point of focus, which is poverty.

How hunger, lack of mitigation and adaptation lead to poverty continue to be masked in preference to terms such as hunger and vulnerabilities. The fumbling in information dissemination in this manner leaves Africa failing to prioritise activities that address both climate change and poverty. In fact, an appreciation of the direct link between climate change and poverty can help Africa address the impact of both poverty and climate change.

It needs to be made clear that those experiencing extreme poverty are pushed to the frontline of climate crises. It is also not clear how people can focus on climate change and poverty in an attempt to address both.

If more emphasis is placed on poverty instead of symptoms of climate change, with people at the centre of everything, they will be able to see the direct link between climate impacts and poverty rather than seeing poverty as a curse especially from the African point of view. It is only in Africa and parts of South East Asia that people think that they were born to be poor. This has led to poverty being institutionalised.

Climate change interventions and action strategies fail because people have not started making sense of poverty as a result of climate change. In this regard, poverty is seen as an act of creation rather than a result of climate change impacts and colonialism. How climate change has had socio-economic impacts has not been sufficiently unpacked. Lack of knowledge to interrogate climate change issues is the reason why people are still invading forests or plundering natural resources for survival because they see nothing wrong with seeking livelihoods that way. To a large cross-section of society, these human activities are normal because they think the forests are for the people, while the people are for the God-given forests. Therefore, you can take the people out of the forests, but no one can take the forests out of these people. This is because people have developed a reciprocal relationship with the forests over the years.

- Open letter to President Mnangagwa

- Feature: ‘It’s worse right now than under Mugabe’: Sikhala pays the price of opposition in solitary cell

- Masvingo turns down fire tender deal

- Human-wildlife conflict drive African wild dogs to extinction

Keep Reading

It is also important for people to see how climate change destroys livelihood options and deepen poverty. This is significant in improving their perceptions so that they will not see poverty as an extension of their culture or an act of creation, whereby the other races were created to benefit more from creation.

The African continent has to be convinced that there is a direct link between climate change and poverty including how this link can be decolonised and deconstructed. There is also need to situate colonialism as having a direct bearing on lack of resources, thereby leading to poverty as a result of centuries-old low levels of industrial development. Furthermore, from the layperson’s point of view, it is not easy to link the emission issue to climate change impacts as the science behind the phenomena is too complex to decipher.

Many inhabitants of the African continent dwell in ecologically fragile zones and marginal environments where they overuse adjacent landscapes for firewood, subsistence and small cash crop production, further endangering the physical environment, health well-being and the lives of their offsprings. These communities are disproportionately threatened by environmental hazards and other risks posed by climate change, leading to poverty.

Also, the meaning of adaptation remains vague since it does not seem to involve conscious responses to climate change and that it is triggered by ecological changes in natural systems. Therefore, climate change adaptation does not seem to be achieving desired results as yet due to inaction and intervention gaps. Climate change will also increase the burden on those who are already poor and vulnerable as well as complicating the capacity of governments to cope with and adapt to severe impacts of climate change, leading to extreme poverty.

- Peter Makwanya is a climate change communicator. He writes in his personal capacity and can be contacted on: [email protected].