OVER the past decade, the Platform for Concerned Citizens (PCC) has continuously pointed out that the crisis in the political economy of the country requires more than another election, more than a forced transition within the ruling party, more than government of national unity, and argued that the country needs a thorough reset.

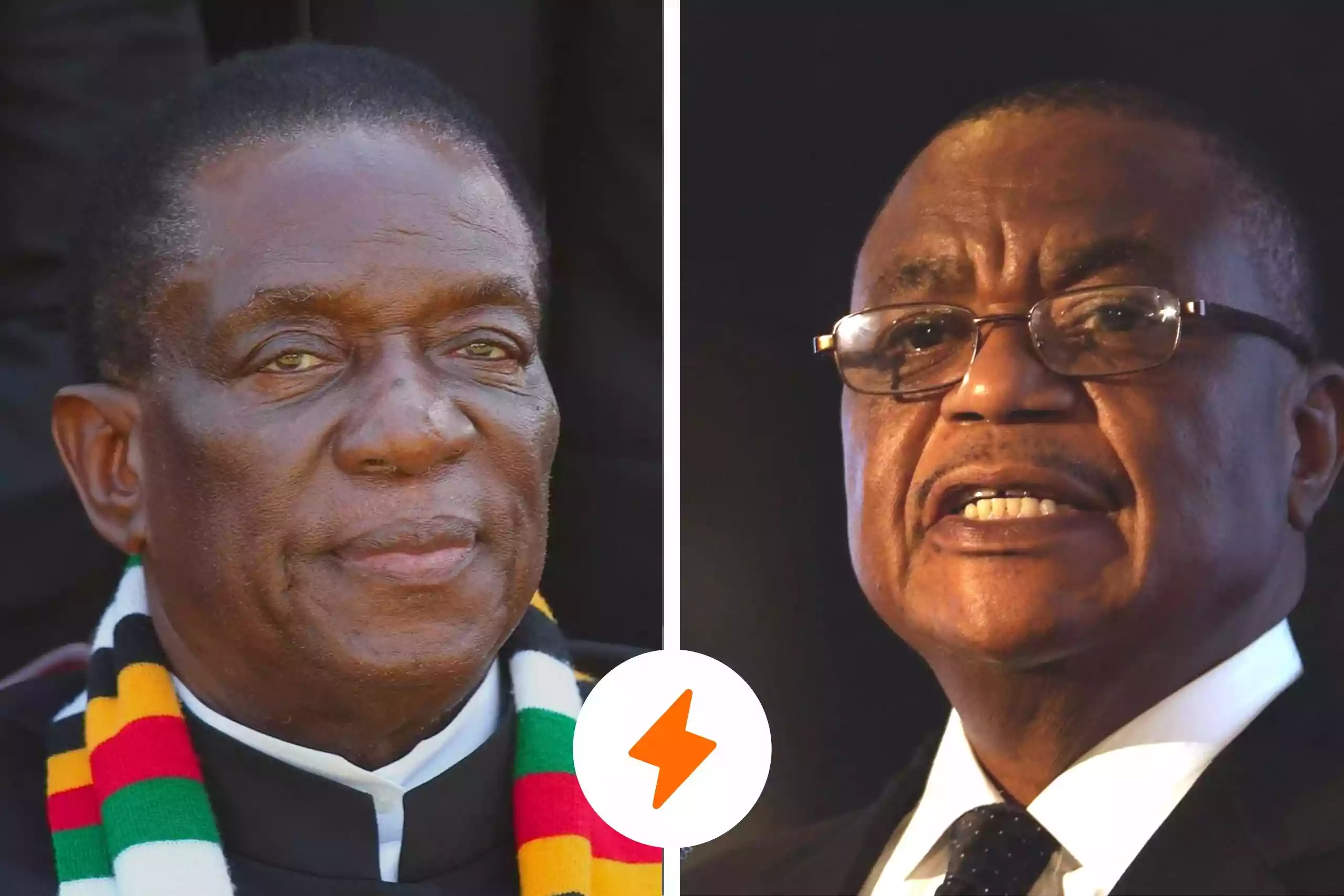

This suggestion gained traction in 2025 and seems even having support within the ruling party in the repeated statements of Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga and war veterans about the capture of the state by a corrupt elite.

In particular, the Chiwenga’s statements are remarkable in how little they have sparked concern within Zanu PF or the government, when it is common cause right around the country that the nexus of corruption and politics is so palpably obvious.

Chiwenga continues to keep silent, and does not bother to defend his claims, because he knows that he is merely expressing what the entire nation knows to be true, as pointed out by Reason Wafawarova.

The government, however, continues with the rhetoric that all is well and the economy is recovering, but scarcely any citizen believes this, and has been critical of the government for nearly a decade.

From 2017 to 2024, more than two-thirds believe the country is going in the wrong direction, more than two-thirds state that their living conditions are very bad or fairly bad, few (13%) claim full-time employment, over half have gone with out cash income (always or many times).

Quite evidently, the vice president is articulating the views of most Zimbabweans, and it is remarkable that this produces no response other than denial or attack.

This was the central point made by the provincial coordinating committee nearly a decade ago: the government had no possibility of serious reform, either politically or economically, and what was true in 2016 is still true in 2026.

- Corruption Watch: Get scared, 2023 is coming

- Corruption Watch: Get scared, 2023 is coming

- Letters: Ensuring Africa’s food security through availability of quality seeds

- Is military's involvement in politics compatible with democracy?

Keep Reading

It has not even been able to take advantage of the soft landing offered by the Arrears Clearance and Debt Relief Process, providing minimal reforms under economic growth and stability, stuck on land tenure reforms, and failing wholesale on governance reforms: the rule of law and protection of fundamental rights and freedoms remain weak and too frequently violated with impunity.

Even constitutionalism is being challenged by the 2030 agenda, and hence it is unsurprising that Zimbabwe is deemed an electoral autocracy, and scores poorly on virtually every international indicator of democracy and governance.

The country is obviously in a state of political paralysis, unable to extract itself from a vicious cycle: the political configuration enables the corruption, and the corruption reinforces and protects the political configuration.

This relationship has been profiled and discussed on multiple Sapes Policy Dialogues in 2024 and 2025, and again recently, but what has been lacking is any clear remedy for the disease.

The single candidate, outside of elections and an unlikely popular uprising, has been the notion of a National Transitional Authority (NTA), all too often dismissed as unlikely given the determination of Zanu PF to hold onto power and the demise of any serious political opposition.

Some may argue for a government of national unity, but past experience demonstrated that will not work when one party holds all the reins of effective power.

Furthermore, how can there be a government of national unity in the complete absence of an opposition? Others argue for popular civic action.

However, this seems unlikely in the absence of any viable organisation to mobilise such action.

There is also a clear lack of trust among the citizenry in political parties, indeed, a near total collapse of political trust in the state, the government, political parties and duty bearers.

In fact, trust appears to extend to almost no one, except religious leaders and civil society organisations. The populace is not apathetic, just without any credible direction to follow, and offered only a continuance of the existing administration for five more years.

Defending the constitution is imperative and has galvanised action, with the Defend the Constitution Platform (DCP) already hard at work.

The groundswell for increasing the term of President Mnangagwa to 2030 is now reaching a critical point with the tabling of the amendment bill for presenting to parliament in the coming session.

Given the majority that Zanu PF holds in parliament, and the demolition of the legitimately-elected opposition through recalls, this is probably a foregone conclusion.

The next move will be an amendment to the constitution using the two-thirds majority that the party holds in parliament: it may not hold such a majority in Senate, but few will bet that the bill will not pass through Senate, given the history of the PVO Bill.

However, the views of the citizenry are clear. No poll, for nearly a decade has shown any support for an extension of terms, and more strongly no support for one-man rule.

From 2017 to 2024, over three-quarters of citizens rejected extending presidential terms and rejected one-man or one-party rule. The proposed amendments, however, are so far-reaching, way beyond the issue of presidential terms — there are 20 individual amendments in total — that the mutterings have grown into furious action and political parties and civil society are mobilising to challenge this.

As Munyaradzi Gwisai and Hopewell Chi’nono pointed out in the most recent Sapes Policy Dialogue, this is much more than extending the president’s term of office, it is about entrenching a political party in power for life, obliterating constitutionalism, and removing all power from the citizenry.

And, as Gwisai pointed out this will be done by 500 persons in parliament, totally ignoring the vast number of citizens (90%), who voted for this constitution: it will remove the fundamental right of the people to decide who rules.

What lies behind this all, according to Gwisai, is the attempt by the zviganandas not merely to extend the life of the current presidency, but the complete capture of the state.

Among the proposed amendments is even the removal of the Zimbabwe Gender Commission, and a public slap in the face for women and the women’s movement, as was pointed out by Chipo Dendere, reducing women’s issues to just another rights issue and ignoring the constitutional commitment to 50/50 in everything social and political.

Actually, as pointed out by all at the Sapes Policy Dialogue, the reason behind the legal manouvering behind the proposed constitutional amendments and the railroading of the amendment through parliament is exactly to avoid a national referendum.

The evidence here is very clear: Zanu PF understands very clearly that the proposal has no attraction for the majority and will fail in the court of public opinion in spectacular fashion.

The counter-campaign on the proposed constitutional changes, being driven by DCP and others — the National Constitutional Assembly, the Movement for Democratic Change, and others — is critical and will need a unified response, but this will be the first step of the deeper struggle that has continued for decades.

Chi’nono pointed out how poorly we have dealt with the political crises since 2000 (and even before), and how our failures have led inexorably to this point, and now we dare not fail.

This is why the challenge to the proposed amendment needs a united approach from everyone: we cannot afford competition for space or egos.

All opponents of the amendment to commit to a common position, the DCP, Constitution Defenders Forum (CDF), the political parties, civil society, and the diaspora; there can be no ownership, only co-operation if the challenge is to succeed.

The problem is the elephant in the room that few seem to have any idea how to move: the broken politics. The notion in 2016 that Zimbabwe had become a securocrat state sounded fanciful to many, even the notion that this might lead to a coup, but this can no longer be denied: a coup did take place and the securocracy has been consolidated into a predatory state.

Predatory states do not reform themselves and keep going until they collapse from all the internal contradictions or more usually from the conflict between factions in the state fighting for control, that terrible nexus between politics and corruption.

This is why the NTA was offered as a soft landing in 2016, but instead we seem to be heading for a hard landing. The country needs desperately a solution, and not one engendered by crisis, and possible violent crisis.

The growing signs of serious conflict within Zanu PF are no cause for celebration but deeply worrying when there is no apparent solution in sight.

Crisis in a state requires a political solution, and not a patching up of allegiances or a phony unity: Zimbabwe has tried both, and they have not resolved the long-standing problem of the national question, avoided since 1980.

As said before repeatedly, the solution lies in a thorough re-set, and only possible through a political settlement and a transitional arrangement.

This is not some new approach to political crisis, but what happens all the time when countries reach breaking point: more than 50 times transitions have taken place globally, either fostered by the ruling party when it is unable to carry on or forced by the opposition forces and the citizenry when the weakness of the government can no longer be tolerated.

Is the missing ingredient the demand for political settlement, national dialogue, and a National Transitional Authority capable of kick starting the massive reform needed and consolidating by a new government in a genuine free and fair election?

- Mandaza and Reeler are co-conveners of the Platform for Concerned Citizens (PCC).