Tafara Mtutu FROM extreme weather conditions to an energy crisis, this year is shaping up to be Europe’s worst year in recent memory.

The continent faces an arduous period ahead as global inflation driven by the Russia-Ukraine conflict weighs on the sombre food and energy outlook. We outline three main events below that have battered the economy throughout 2022, and economic implications on global trade.

Russia-Ukraine conflict The war that quickly upended global markets has taken a huge toll on Europe given the warring nations’ contribution to food and energy. Europe’s dependence on Russia compounded the continent’s challenges given that there remains no permanent and cleaner energy alternative to Russia’s energy.

As a result, the continent has since suffered the brunt of Russia’s weaponisation of oil and gas in retaliation for economic sanctions. To mitigate against growing energy concerns, several European countries have ramped up coal imports from South America, South Africa, Australia and Colombia to make up for the deficit.

However, the price of coal has also surged by 154% to US$350,25/tonne in the year to date, and this has prompted further measures, such as calculated blackouts by European Union (EU) member states, more commonly known as load-shedding in Zimbabwe.

Heatwaves Having encountered fatal incidences of heatwaves in 2003, 2006, 2010, 2015, 2018, 2019 and 2020 that claimed the lives of over 240 000 people, Europe faces yet another brutal heatwave in 2022.

The economic losses and food inflation accruing from the latest heatwave have seen the markets coining the phenomenon “heatflation”.

According to the EU, yields of maize, sunflower and soya beans are expected to drop by roughly 9% this year because of the heatwaves and their ripple effects on agricultural production.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Temperatures in Europe have now risen nearly twice as fast as the global average of 1,1 degrees C, and this has affected optimal conditions necessary for food production in several parts of the continent.

Key among these are the drought conditions, whose effects will be unpacked shortly. The high temperatures are also expected to affect tourist arrivals because of the uncomfortable heat and its impact on key infrastructure, such as roads and landing strips, with some tourists opting to visit Europe earlier than the start of the traditional summer season.

Drought An unusually dry winter followed by record-breaking summer temperatures and repeated heatwaves have resulted in record-low water levels in many of Europe’s rivers.

Germany’s Rhine, for example, is eerily close to being closed to commercial traffic because of very low levels caused by drought, authorities and industry have warned.

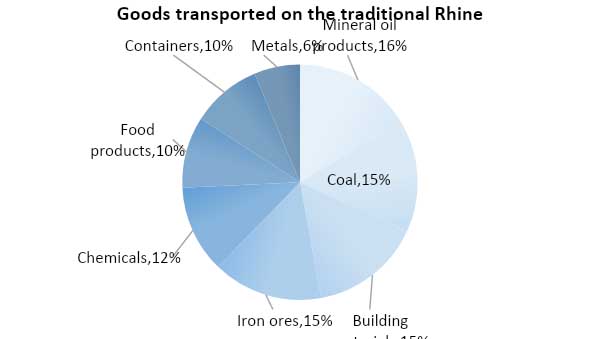

The 1 200 km-long river is an essential freight route that transports 200 million tonnes of cargo every year, and these weather-related constraints could perpetuate supply disruptions caused by Covid-19. Considering that the Rhine transports the immediate energy alternative coal as well as raw materials for the continent’s wider productive industries, the disruption could warrant a further cut on growth prospects. While alternative modes of transport are available, the cost of moving bulk goods via roads is far more costly than freight, and this would fan current inflationary pressures. Growth prospects for Europe were recently trimmed down to 2,6% by the IMF and 1% by the World Bank in response to some of these developments.

We opine that this will open up an opportunity for exporters who could scale up food exports to Europe in response to the constraints to supply by local farmers, who have also lost over 80 000 workers in the horticulture industry alone since Brexit.

Zimbabwe features among horticulture exporters to Europe with produce such as blueberries, mange touts, baby sugar snaps and citrus fruits on shelves in several European countries.

This could bolster export receipts for ZSE-listed horticultural companies, such as Ariston, Tanganda Tea, and Hippo Valley Estates.

We also note the potential in coal exports from Zimbabwe, albeit small. The increase in demand for coal has significantly pushed the price of coal and, at face value, this could benefit Zimbabwe. The southern African country has the 38th largest reserves of coal in the world with an estimated 550 million tonnes of coal reserves. The country was also the 43rd largest exporter of coal in 2021 after hauling coal worth US$9 million to export markets largely domiciled in sub-Saharan Africa. However, the export potential of Zimbabwe’s coal is hampered by its high sulphur content and local power demands. Zimbabwe’s coal has a sulphur content of around 1,3%, making it less marketable in comparison to coal from other coal exporters with relatively lower sulphur content that ranges between 0,45% and 1,0%.

In addition, the country also depends on coal for local power generation despite obsolete equipment. Thermal power has historically accounted for 24% of total electricity supply in Zimbabwe, and authorities sometimes ring-fence coal exports in a bid to ensure that thermal power stations are stocked whenever they are not under maintenance.

- Mtutu is a research analyst at Morgan & Co. — [email protected] or +263 774 795 854.