By Kudzai Mazvarirwofa/Evidence Chenjerai After feeding his chickens and turkeys, Amos sifts through a heap of second-hand clothes, shaking down the ones he will sell from his backyard. This is far from the retirement he had imagined.

The former teacher lives in a dense suburb of Mutare, a city on the foothills of the Manica Highlands in eastern Zimbabwe. After 38 years of service, he expected to enjoy his pension when he retired in 2019. Instead, the monthly payout of $15 000 (US$154) has forced him to work as a poultry farmer and salesman to make ends meet.

The pension is “barely enough” to survive, says Amos, who asked to use only his first name for fear of reprisals. Sitting on his verandah, the 64-year-old explains how more than half of his pension is spent on medication to treat high blood pressure and diabetes. He is also the legal guardian for his grandchildren and pays for their school fees. The extra jobs have become a necessity.

Amos is not an outlier in Zimbabwe, where two decades of political and economic turmoil have devalued pensions and plunged millions of retirees into poverty. Hyperinflation that began in 1999 eventually led to the collapse of the Zimbabwe dollar in 2009, the introduction of other currencies, including the United States dollar and the eroding pensions. Economic austerity measures in 2018 diminished pensions once again.

In the education sector, the pension crisis is fuelling another crisis, according to teachers’ unions, which say the plight of retired teachers is putting the future of the profession in jeopardy.

“People are now shunning teaching, with the country losing [its] best minds through brain drain” as Zimbabweans migrate for better-paid jobs, says Peter Machenjera, spokesperson of the Progressive Teachers Union of Zimbabwe. “Teachers’ colleges right now are struggling to enrol new students.”

Working teachers are voicing their discontent over poor salaries and conditions. There have been several countrywide strikes in recent years, educators demanding improvement in their conditions of service and remuneration. Concerns among teachers have intensified during the coronavirus pandemic as a shortage of personal protective equipment led to a new wave of protests.

Paltry salaries and measly retirement packages have pushed current and former teachers “into perpetual poverty,” Machenjera says. “It can best be described as an insult to patriotic teachers who have served the government for years.”

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

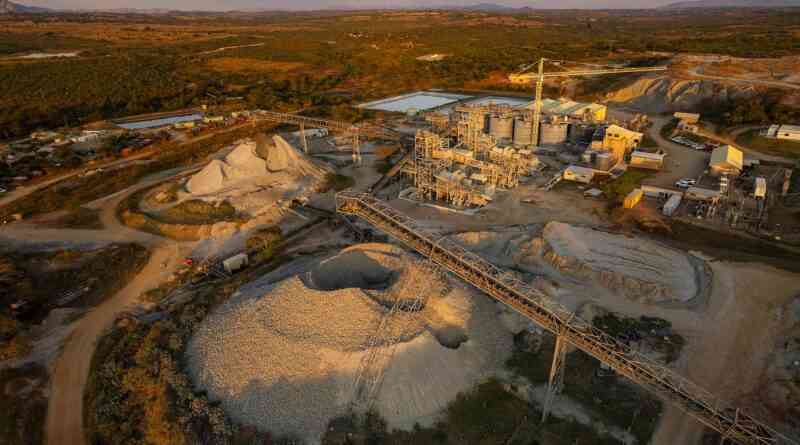

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Taungana Blessing Ndoro, spokesperson for the Primary and Secondary Education ministry, refutes the claim that inadequate pensions makes it difficult to recruit talented teachers. A poor pension “does not equate to poor-quality teachers,” he says. “We have quality teachers in our schools.”

He didn’t respond to teachers’ concerns about poor salaries. But on the safety from the pandemic, he says the government has spent $909 million (US$9,4 million) on protective materials such as masks for all public schools. The pension crisis in Zimbabwe has been exacerbated by endemic corruption in the public sector.

“Those who are supposed to be managing pension funds, are stealing from the coffers,” says Obert Masaraure, president of the Amalgamated Rural Teachers Union of Zimbabwe. He refers to a 2018 probe that found that executives of a prominent pension funds pocketed allowances even as the fund failed to honour payouts to members. “How can we convince our youth to trust in education if their educators end up paupers?”

Zimbabwean pensioners, including but not limited to former teachers, have raised numerous complaints with the government in recent years. Paul Mavima, Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare minister, says his ministry has been asked to negotiate with local authorities to reduce or waive taxes that pensioners are required to pay. “We will be doing necessary consultations,” he says.

Back in Mutare, in a neighbourhood adjacent to where Amos lives, another retired teacher also faces financial problems.

Mutape remembers the golden era of teaching in Zimbabwe. Back in the 1980s, he says, teaching was a respected profession that came with the guarantee of a plump retirement package.

“We used to send our children to good schools and live a comfortable life envied by many; I managed to buy a piece of land and built a house,” says Mutape, who asked to use a honorific that means “wise elder” in the local dialect, Ndau, instead of using his real name. He too fears reprisals for his views.

The educators, who retired in the 1990s and early 2000s received pensions that made it possible for them to buy cars and even start businesses, Mutape says.

“Most of them got set up for life, which is what is expected of retirement.”

He says his payout, which is equivalent to US$81 a month is “a mockery” after 33 years of service.

The 65-year-old now grows and sells vegetables in his garden to supplement his pension. He is disheartened that it has come to this. “We are not being given the recognition we deserve.”

- Kudzai Mazvarirwofa and Evidence Chenjerai work for Global Press Journal and are both based in Harare, Zimbabwe.