By Fidelis Manyuchi

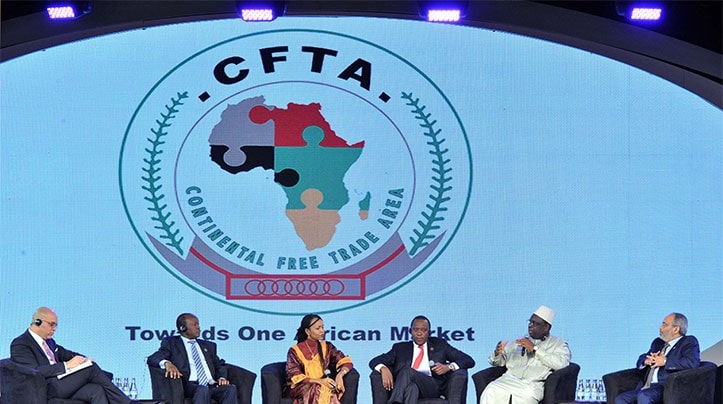

THE agreement forming the African Free Trade Area came into force on May 30, 2019, and was launched on January 1 2021.

The parties to the agreement are the member States of the African Union which have come together to create a 50-year agenda.

The general objectives of the AfCTA are to create a single market for goods and services. The agreement seeks to achieve this by facilitating the movement of persons in order to deepen economic integration of the African continent. In addition to this, the agreement seeks to promote and attain sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development, gender equality and structural transformation of the State parties.

The agreement also aims to enhance the competitiveness of the economies of State parties within the continent and the global market. Finally, the agreement aims to promote industrial development through diversification and regional value chain development, agricultural development and food security and to resolve the challenges of multiple and overlapping memberships.

The specific objectives of the agreement are to progressively eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods. This involves the alignment and harmonisation of competition, investment and intellectual property laws.

The agreement also aims to establish a mechanism for the settlement of disputes that might arise on the rights and obligations of the State parties. An administrative outpost is also created which is tasked with the implementation and administration of the agreement.

Some of the fundamental principles that underlie the agreement are flexibility, special and differential treatment, transparency and disclosure of information, preservation of the acquis, most-favoured-nation treatment and reciprocity.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The agreement has been met with much excitement from different players, across the continent. Political players are especially proud of their achievement. This article seeks to highlight the main legal hurdle that needs to be dealt with if this agreement is to bring about any meaningful change in Africa.

Africa is notorious for concluding agreements forming regional economic communities. Examples of these are: the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA); the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa); the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD); the East African Community (EAC); the Economic Community of Central African States (Eccas); the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas); the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the Southern African Development Community (Sadc). These bloc agreement are also acknowledged in the AfCTA.

Many people see the prospects of a single-market bringing economic prosperity to Africa. If it was a simple matter of concluding agreements, the AfCTA should not have seen the light of day as its objectives would have already been met through the numerous regional economic agreements listed above. The bloc agreements would have resulted in the achievement of the economic objectives for Africa. What is clear is that without proper policies that result in sustainable institutions, 2063 (as per the agreement) will arrive and none of the objectives of the agreement will have been achieved.

This paper posits that the main legal hurdle that the continent has to overcome is centred on the issue of the rule of law. The concept of the rule of law implies that each and every person is subject to the law. Everyone is subjected to clear laws stemming from well-defined sources of law. In the context of AfCTA this means that all the State Parties are subjected to the same law and no State party is above the other.

Unfortunately, there is no consensus on what concept of the rule of law entails in Africa. Africa is not one big village made up of people living together in one big hut. Africa is made up of 55 countries with about 1,2 billion people.

These countries are further fragmented into societies made up of people from different tribes and ethnic backgrounds. All these people ascribe a different meaning to the concept of the rule of law and the whole spectrum is covered, from total disregard of the law to full reverence of the law.

Incidents which prove this are well documented throughout history up to modern times.

There are some extreme instances of lack of respect of the rule of law that border on lawlessness. Examples of this are the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, the Zimbabwean land reform of the 2000s, the South African Umkhonto We Sizwe standoff of 2021.

After the land reform in Zimbabwe, some aggrieved parties sought relief with the Sadc tribunal contesting the acquisition of their agricultural land.

The petition was based on the fact that Zimbabwe had breached the Sadc Treaty which had been signed on August 17 1992, and ratified by Parliament on November 17 1992.

The Sadc Tribunal found that the aggrieved parties had been denied access to courts in Zimbabwe and that they were entitled to fair compensation. The government refused to comply with the ruling despite the fact that Sadc Tribunal judgments are final and binding in accordance with Article 32(3) of the treaty.

The legitimacy of the Sadc Tribunal was impugned and vitiated by both the members of the executive and the Judiciary.

The government ultimately pulled out of the Sadc Tribunal. This demonstrated a total disregard of the rule of law which involved deciding what the law was when it was convenient for the government.

Fast forward a couple of years later, the new government has decided to compensate the farmers from whom the land was acquired.

This might be testament to the change of stance of the government when it comes to the issue of the rule of law.

In South Africa, there was an Umkhonto We Sizwe standoff in 2021. This involved the former South African war veterans defending the former president Jacob Zuma’s decision not to testify in the Zondo Commission. They questioned the legitimacy of the commission and insinuated that Jacob Zuma was above the law.

Fortunately the law prevailed and Jacob Zuma was arrested and incarcerated for contempt. This resulted in violent protests, massive looting and lawlessness.

These unfortunate examples can be juxtaposed with instances in which the rule of law was respected. An example of this is the Kenyan Constitutional Court decision on elections. In this instance the Constitutional Court successfully defended the Constitution of Kenya.

Another example is the elections in Zambia where there was a peaceful transfer of power.

The above are a few examples. The examples are infinite across Africa. From a legal perspective, the rule of law is central to the success of the AfCTA. Since the agreement is between multiple parties, it is natural that disputes are going to arise. The agreement itself envisages this and constitutes a dispute settlement body. I submit that the efficacy of this body is depended on the respect that it is given by the member States and this respect is bound to be the same as the respect they ascribe to the rule of law. If some of the member States do not give the dispute settlement body the authority and reverence it deserves, the body will essentially be a toothless entity. A precedent has already been set by Zimbabwe which refused to recognise the decisions of the Sadc Tribunal.

It is not very difficult to harmonise the intellectual property laws, investment laws and competition laws across the continent. What is difficult is equally adhering to those laws. Some of the African countries are notorious for expropriating private property without compensation. Again, Zimbabwe is well known for moving from one currency to the other without compensating anyone for the exchange loss. Without respect for private property, which is in itself respect for the rule of law, it is difficult to imagine substantial economic change in Africa.

It is highly unlikely that investors will flock to Africa and make sustainable investments if the quality of African institutions is still lacking. The issues of corruption, lack of accountability and transparency have a huge effect on investment. All these issues can be dealt with, if there is unwavering respect of the rule of law. South Africa is well known for constituting commissions of inquiry which, unfortunately, do not result in meaningful arrests.

Inasmuch as the rule of law brings about legal certainty, which aids in attracting foreign investment, it must also be used as an anchor from which beneficiation and other industrial policies stem from. Developing a free market for foreign goods and services is akin to opening up Africa for others to thrive while the continent remains a producer and exporter of raw materials.

In conclusion, in order for the agreement to bring any real change, State actors across Africa need to seriously look into the issue of the rule of law. There is need for a serious shift from the culture of impunity to a culture in which the law is respected. The respect of the rule of law has to be absolute. Without this, this agreement will only succeed in creating a costly political talkshop spewing nothing but the same old tired rhetoric. The difference being, instead of blaming western or eastern countries, it will be African against African and if it degenerates further, the African identity will quickly be ditched for a country identity, which will be in turn ditched for tribal or ethnic identity. Brexit has set precedent for this.