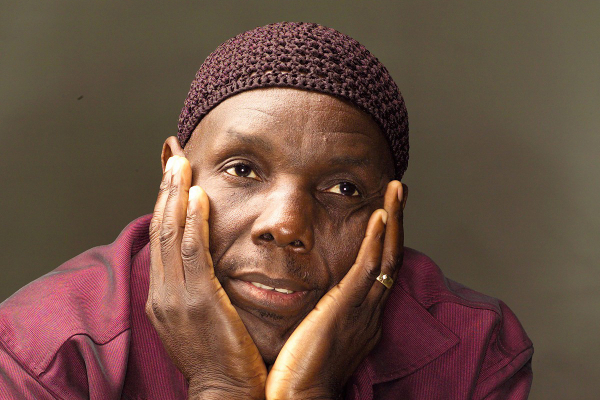

Between the Lines: BENIAH MUNENGWA

IT was in a mentor’s office that I got the awakening to everything people did; there was a deep emotional and psychological string attached to it, no matter what thing they do may appear simple.

One such component is the disparity of the choice of music by mostly mine, tobacco farmers and rural-based people when compared to that of a class of people whose jobs are not physically taxing and have less risks.

The type of people or the mood that suits, let’s say, sungura ace Alick Macheso’s music which some find soothing and refreshing is different to those who find the same emotions in the late music icon and national hero Oliver “Tuku” Mtukudzi’s music.

Spending most of their lifetime in mines, risking imminent danger and away from light and life, the mine worker finds solace in music with lengthy guitars that evoke a spirit of dance and the loosening of the body, without the mind being imprisoned in some emotional complex that takes it into deep thought.

They prefer to feel that guitar that churns out rhythm, that lasts for minutes uninterrupted and when a voice emerges, they just want something to dance along to and unbundle themselves from the attachment to death, fear, inadequacy, completion and terror — and be liberated.

Many have wondered why gold panners and tobacco farmers, when given the chance, get carried away with fast lives, but Rousseau’s concept of alienation empowers the reader of social events in life.

Franz Kafka writes: “This kind of Taylorised life is a terrible curse from which only hunger and misery can grow, instead of the longed-for wealth and profit.” It is the guitar strings and the high sounding drum beats that many then use to unshackle themselves from the realisation that they themselves are alienated from their gold or their tobacco, but are attached to the health risks associated with tobacco production and the ever near-death experiences found in mines and the realisation that life simply can come to an end.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

But for the settled ones, whose daily routines are full of refreshing deeds and acts, music that evokes thought and pull them down as they sip the wise waters stands mostly as their choice.

This comparison would be of no relevance to me if it failed to descend to the literary scene, where people who find the reading of texts like, Waiting for the Rain, Echoing Silence, House of Hunger, Butterfly Burning, To My Children’s Children, The Promised Land and The Last of the Empire, on average, a deed that cannot be done merely for luxury. And anyone who attempts to do it that way barely finishes the text.

In the same line of argument, it must be noted that, most likely, those who find the reading of the above mentioned texts accessible, mostly detest the reading of texts that lack deep tenets associated with high art. These genres include the romance, subject-oriented texts, for example, HIV and Aids issues, colloquial texts and folklore.

The opposite is true. The same that find the reading of these texts haunting tasks, find solace in reading texts in the category of, let’s say, motivational texts, do it yourself, religious texts and romance.

This article presents a thesis that the restraint to the extension of reading cultures is not limited to economic and physical factors like the affordability of a book or the availability of a book to a reading audience, but the penetrability of a text in terms of stimulating and striking the right chords that allow a person to carry on.

After reading Butterfly Burning, I recall, I had a headache that lasted for almost two weeks. In those two weeks, my inner intuition struggled to handle its relationship with the world, all in all seeing the universe as absurd and questioning most of life’s perceptions, beliefs and functionalities.

This is the same feeling that many get upon reading Marechera’s work and as a result, many hesitate reading or finishing reading his works, seeing it as some form of emotional torture that is not worth going through.

Upon reading Echoing Silence, a feeling of having similar struggles with Munashe, in the end becoming as haunted as him grows.

Thus, these texts stand as a reserve for a few, an electric fence that not all will manage to cross. It remains a typical scenario of taking a goat through water. From this, an explanation on why many students who do literature as a subject in advanced study prefer using internet sources and secondary sources as alternative routes for reading primary text thus emerges.

Many a time, book fanatics are warned that for being book worms, one day they might end up mad men or be like ‘Marechera’.

One literary fundi noted: “The metaphoric aspects of books like Waiting for the Rain are not easily comprehended by the layman.” For an ordinary person to pick-up the pieces of Garabha’s deeds, connect with the struggles in Umuofia, relate to Mahoso’s Footprints about the Bantustan, is a piece meal that not many will swallow.

Some books are clearly evidence of outbursts of artistic inspiration, manifesting over a historical timeframe, yet some do not necessarily call for inspiration either from the writer’s part or from the reading end.

Therefore, the technicality of some books still stands as a deterrent to the consuming public, with class struggle, intellectual prowess and social orientation among the key components that determine who takes what form of art and with what effect as in all other forms of art and genres.