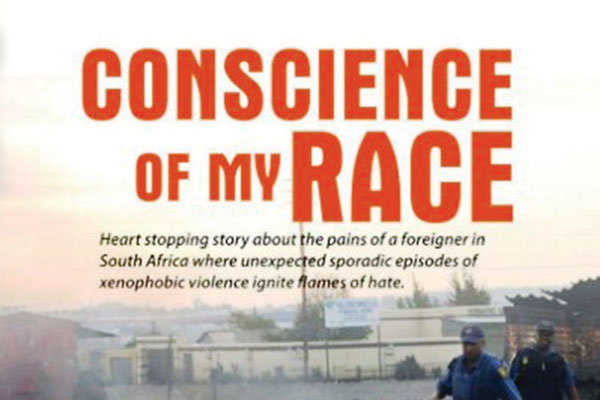

THE front cover of Elias Mambo’s publication, Conscience of My Race, depicts a picture of a man trapped in a “necklace”— euphemism of forcing a tyre around some’s neck and setting it on fire — itself an enduring and defining image of the xenophobic attacks that rocked South Africa in 2010.

BOOK REVIEW: PHILLIP CHIDAVAENZI

Mambo is an investigative journalist and his debut single-authored creative literary work betrays that fact — not that it is a poor effort, but the regard for the sanctity of fact over fiction is almost overwhelming.

Conscience of My Race tells the story of a young man trapped in South Africa, the proverbial land of gold, presumably a safe economic haven away from the political and economic terrors of his home country of Zimbabwe. His security shell, however, is cracked open as black-on-black violence rocks the “Rainbow Nation” leaving many dead and injured.

In only 61 pages that seamlessly blend prose fiction, poetry and fact, Mambo uses such fine language to tell a gripping story touching on history, diplomatic relations, literature and geography in one sweep. While the steam of breath quickly evaporates, the story he tells with so much passion will not be quickly washed away like chalk dust in the rain, but is bound to stick with you and haunt you for a long time after putting away the book.

Throughout the text, at some points, it becomes difficult to separate the journalist from the author, to separate Elias the main character narrating the story from Mambo the author. On many levels, this is a deeply felt book.

Perhaps the book’s greatest strength lies in the author’s ability to be sacrilegious, poking fun at the rigours of literary style, trashing the form book. Here, a novel is broken midway by a series of poems, after which the author picks up the thread and writes on as if there has been no break.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

It almost feels like the poems came to him in an unexpected burst of inspiration so strong he could not contain it, and was forced to temporarily stop the novel and pen the poems before picking up his story. Strangely, he is able to make the poems a part of the story, as they mirror the same rage, the same frustrations and disillusionment that colour the prose.

The poems — Zimbabwe, Thoughts, Protestant Poetry, Xenophobia and Dictatorship — allow the persona to exhaust the rage he feels. He is angry at his government and its failed political and economic policies, which have driven thousands like him into the Diaspora in search of the often illusive proverbial greener pastures. Protestant Poetry, for instance, is passed on as a poem of “a nation that reaps a harvest of turmoil” (pp28) while in Dictatorship, the poet longs for the demise of the dictatorial regime that governs his nation, which will pave way for peace in his home country.

Mambo writes with a singsong cadence that makes his writing almost musical. His descriptions are cinematographic, too. For instance, he writes on page 20 that: “The clouds outside began to gather, forming a big black blanket covering the whole sky. A spider web of fire illuminated the sky into a brilliant yellow. Thunder roared like a thousand drums being rolled at once.” The reader can even hear the drum roll!

Mambo, through the protagonist, has his philosophical moments, too. In fact, throughout the text, much of the story takes place in the protagonist’s mind as he reflects on what is happening around him. He is not just an observer of what is happening around him, but his active mind captures and processes everything. He is a widely read intellectual who has consumed the works of one of the fathers of Sociology, Sigmund Freud, Africa’s literature greats Chinua Achebe and Dambudzo Marechera as well as William Shakespeare.

The protagonist sounds like an echo of Munashe in Alexander Kanengoni’s liberation war classic, Echoing Silences (1997). Just as Munashe struggles to make sense of a war in which he is a passive participant, Elias also battles to grasp the reasons fuelling the xenophobic attacks. He seeks an answer beyond the South Africans’ anger: “This mob reminded me of that mob in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Some say the mob goes with the wind. Reasoning is left behind as action precedes it. Others say insanity in individuals is something rare — but in groups, parties, nations and epochs. It is the rule. These people were angry, very angry. There was nothing to stop this river from flowing.” (pp17)

This is a classic that deserves a place in any reader’s bookshelf.

Feedback: [email protected]