Jinja, Uganda — Mambera Hellem tells her friends and neighbours about all forms of contraception, yet despite their high HIV risk, she knows many of the women she speaks to will not use condoms.

IPS

When I ask Mambera and her friend, Kyolaba Amina, if it is a woman or a man who decides to wear a condom, Kyolaba giggles softly at my question.

“It is not easy for a woman to initiate condom use because it will bring about questions of trust,” Mambera says.

“The man would ask the wife if she does not trust him.”

Kyolaba, though, has deeper suspicions, adding that some men “deliberately want to infect their wives”.

“I don’t know why men do that, but I have seen a case where a woman and a man had discordant (HIV) results, but the man did not want to use condoms, because before, they were having unprotected sex, why (not) now,” she says.

In a country where many myths abound around contraceptives and their side effects, the most popular forms of contraception for the women in this community are depo-provera “depo” and intrauterine device (IUD) implants.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

“You find many women who have children every year, so it is such women we reach out to,” Mambera says.

Some women even prefer IUDs or depo, because, unlike condoms, they can keep them secret from their husbands, and this is not the only aspect of their sex lives which women keep secret, Kyolaba says

“We do talk about HIV and tell the women to go for testing, but many women are afraid to tell their husbands about this thing and they do secretly come for testing,” she says.

“I have an example of my neighbour, who came to the clinic and tested positive, but has kept this a secret, not told her husband, because it could lead to violence in the home.”

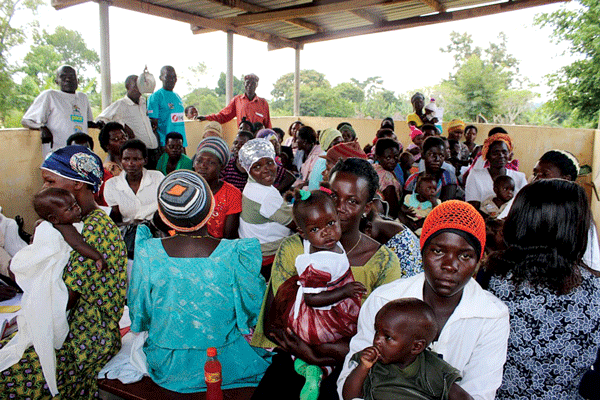

As I speak to Mambera and Kyolaba in the backyard of the Christa clinic in Jinja, a group of women cradling babies on their laps watch as a nurse demonstrates how to use a condom.

The clinic serves a poor community near the banks of Lake Victoria and the source of the Nile River providing free and low cost family planning services.

Services such as these are patchy at best in Uganda, which has one of the highest birth rates in the world: the average Ugandan women will give birth to six babies during her lifetime.

A different, more concerning, statistic has emerged in Uganda and other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa in recent years.

Young women are becoming HIV positive much younger than their male peers.

By the time she is 21, a young woman in Uganda has a one in 10 chance of being HIV positive.

A young woman between the ages of 15 to 24 is more than twice as likely as a young man in the same age range to be HIV positive.

According to the latest available statistics from 2011, 4,9% of women and girls between these ages will be HIV positive, versus only 2,1% of men, with sharp rises for girls between the ages of 15 and 21.

Without being able to influence whether their sexual partner wears a condom, these young women have little ability to protect themselves from becoming HIV positive, since condoms are the only form of contraception that also protects against sexually transmitted infections and diseases.

Akinyele Eric Dairo, an officer in charge of the UN Family Planning Agency (UNFPA) in Uganda, agrees with Mambera’s observations that women have less influence over condom use than men.

“When it comes to condom use, men have more influence than the women,” he says.

“Condom use brings about a sense of dependence on the part of a woman.”

Dairo adds that the preference for other forms of contraception also reflects young unmarried women’s fears of pregnancy.

“The effects of pregnancy manifest much faster than the effects of HIV and sexually transmitted infections,” he says. As Catherine, a nurse at Jinja hospital, puts it: “The major fear is pregnancy. They don’t know that they can get other problems.”

This may, in part, be because access to anti-retroviral treatment has greatly reduced not only the spread of HIV, but also the stigma around the disease.

“People are saying that this is like being diabetic,” Catherine says.

The increased availability of antiretrovirals has led to significant progress in the fight against Aids in Sub-Saharan Africa, however, this progress could potentially be set back if prevention efforts among a demographic as large as adolescent girls continue to fail.

This is why Loyce Maturi, a 23-year-old woman from Zimbabwe, who has been HIV positive since she was 16, was invited to deliver the keynote address a high level United Nations meeting on Aids in New York, the United States, earlier this year.

“Sharing my story, I hope it reflected that as adolescents girls and young women we are vulnerable, at risk, most infected and affected by the epidemics than any other age group,” Maturi said.

Scribbled in the margins of a copy of her speech later shared with the media is an addition: “There is a need for us to priorities (sic) key populations MSM (men who have sex with men), sex workers, people who inject drugs, prisons (sic) and migrants.”

Yet while the HIV and Aids response has focused on these high-risk groups, none of them are vulnerable simply because of their gender or age, which is why addressing the reasons why young girls have such a high rate of infection is so important.

As Dairo explains, girls are often forced into early sexual relationships and early marriage, often with much older men.

Girls are also at risk because they face violence, including sexual violence, and because they have less access to education and economic resources than their male peers, Dairo says.

This forces young girls to find older men, who help them out with money for bus fare and school fees, creating a very unequal power dynamic, where it would be very unlikely a girl could decide if her partner wears a condom.

This is why, says Dairo, teaching young people how to use condoms alone is not enough, if the many gender inequalities, which lead to young women’s higher risk, are not also addressed.