PEOPLE on the fringes of Save Valley Conservancy (SVC) near Chipinge district are living in fear of wildlife such as lions and elephants that freely roam the area.

BY TONDERAYI MATONHO

Some parents have been forced to withdraw their children from school amid fears they would be attacked by wild animals on their way to and from school.

Safari industry operators, tourism development players and communities are now pressing for a revamp of the country’s safari industry and trophy hunting standards and practices to ensure sustainable utilisation of the abundant resource.

Zimbabwe Safari Operators’ chairman Emmanuel Fundira recently said the industry was lucrative and generated over $200m a year. But only about 10% of this goes to community projects.

“There is growing need for stakeholders to look into the industry and so-called sustainable development programmes. We need transparency and accountability so that communities and the broader tourism sector can also benefit unlike the current situation where only a few players are benefitting,” Fundira said.

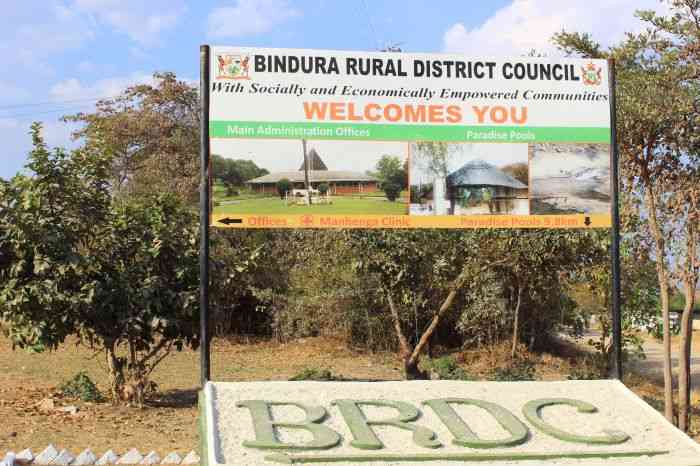

A renowned environment expert and consultant who spoke on condition of anonymity said: “Wildlife benefit-sharing in Campfire (Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources) projects is currently being reviewed by donor partners where most benefits are mostly enjoyed by local district councils and only flow in drips to communities.”

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

He noted that sustainable development was a key model that respects the environment while offering local people financial benefits from wildlife.

Chipinge villagers recently petitioned Parliament to intervene and resolve their conflicts with wildlife conservationists in the SVC.

Yet, conservancy owners accused the villagers of vandalising the perimeter fence surrounding the area increasing endless human-wildlife conflicts.

A project officer for an NGO operating in the district, Levison Maposa said he had observed over the last two decades that the role of local people was yet to be recognised in sustainable development.

“There has been a lot of private sector engagement resulting in more benefits accruing to foreigners and local elites rather than the poor,” Maposa said, adding that this had raised more questions about evaluating the trade-off between improved opportunities for some versus less equality in development for many.

Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA) director Mutuso Dhliwayo said equitable resource allocation must be improved, and that can only be done if local communities are empowered.

“Rural communities living next to rich wildlife protected areas and mineral-rich zones should have the power to express their views on the availability of resources, especially water, wildlife for hunting, mining and of course, rich and arable land for agriculture,” Dhliwayo said.

Experts argued that the concept of Community-Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM) noted policy-makers recognised that for wildlife to persist outside protected areas on private and communal lands, it must be an economically competitive land use option for landholders.

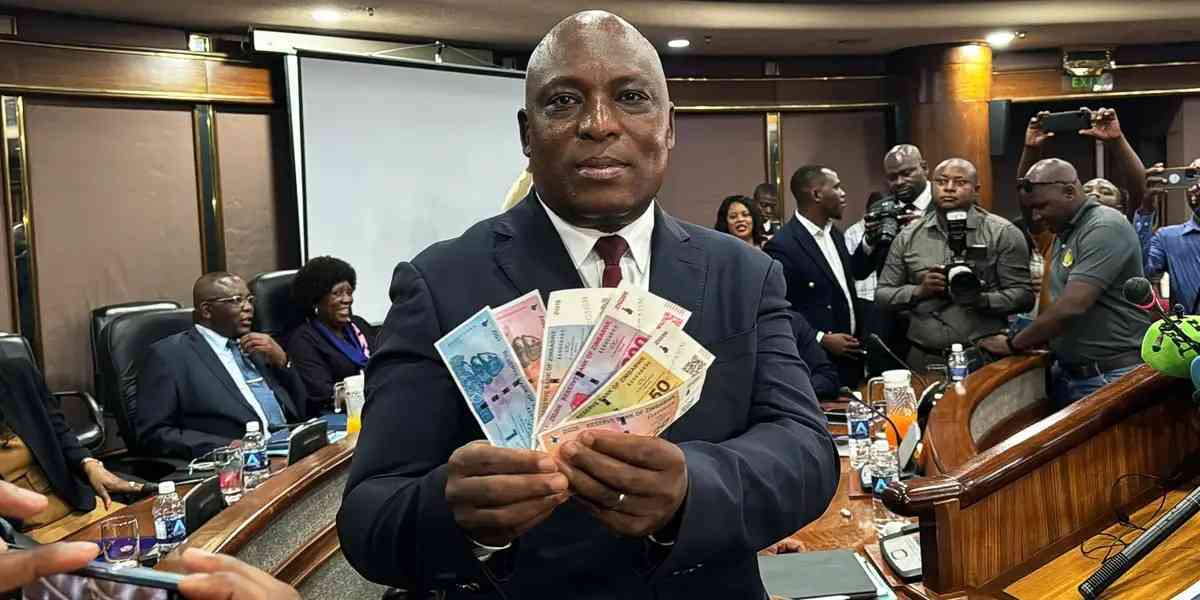

CAMPFIRE director Charles Jonga, recently said 45% of the gross hunting revenue goes to communities largely controlled by rural district councils while 55% goes to safari industry operators.

But the Centre for Applied Social Sciences (CASS) at the University of Zimbabwe contended a key question at the heart of the tourism debate in Zimbabwe is what share of the financial benefits should go to communities.

As is normal with the tourism sector, the high tourism fees of several hundred or thousands of dollars per day go to private players, NGOs and government, with little left for local people.

Development experts said rural communities hold the greatest potential for employment, provided there is sufficient investment with transparency from the safari industry, CBNRM and Campfire projects.

Kenya, the first African country to completely outlaw trophy-hunting, enjoys a vibrant safari industry, worth nearly $1 billion to the annual economy. In early 2014, Botswana banned trophy-hunting to promote eco-tourism. It reportedly earns over $400 million per year from tourism, foreign direct investment, donor aid and only a tiny fraction from trophy hunting.

Yet in Zimbabwe, foreign donor fatigue, largely due to the unfavourable socio-economic and political milieu, has also contributed to lack of community transformation. Donors and tourists have been heavily frustrated by an economy characterised by unwarranted land invasions from the politically-connected, poaching and wanton killing of wildlife to feed local and international syndicates at the expense of communities.

According to safari industry sources the sector is controlled by wealthy and well-connected individuals who are benefiting but disregarding fair and best practices for sustainable development. Trophy hunting for big game is also a controversial blood sport.

Implementation of Zimbabwe’s Wildlife-based Land Reform Policy supported by NGOs and government in the safari industry through donor-support has not been consistent.

“Programmes such as the CBNRM and the Campfire, should continue leading by example, showing people and communities how tourism and conservation can be a benefit rather than a burden” Zimbabwe National Environment Trust, executive director Joseph Tasosa said.

The International Institute for Environment and Development also says the Campfire programme used to generate more than $20 million in revenues for local communities and district governments from 1989 to 2001.

But in recent years, there have not been any land and wildlife inventories so as to have a clearer and more up-to-date picture of the wildlife industry and the available land resources.

According to Zela’s Dhliwayo, there must be robust dialogue and debate at national level, debating government policies on rural development, the safari industry’s role and NGO operations by Parliament, particularly as Sustainable Development Goals replace the Millennium Development Goals as new models for economic growth.