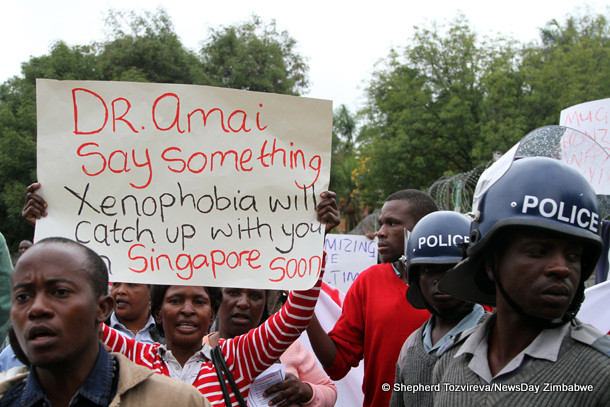

THIS week, Africa has been gripped by the horrifying images coming out of South Africa, in which thousands of foreigners have been hounded out of their homes and businesses by xenophobic mobs and forced to take refuge in police stations and camps.

The common narrative in trying to explain – or at least understand – these attacks, is that foreigners (mostly, meaning black Africans north of the Limpopo) have flooded South Africa, taking away the jobs and opportunities of locals.

South Africa’s political, economic and social problems are many, complex and layered, and it is futile trying to outline them all in one article.

But there’s something in the structure of the South African economy that partly explains its shocking inequality and crime, sluggish growth, and why the ruling African National Congress (ANC) government has struggled to deliver on its promises of prosperity; hence the scapegoating of “foreign” Africans.

It starts not in the spaza shops of the Durban or Johannesburg townships, but on the gleamy floors of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Too much of a “good” thing.

A few weeks ago, reports out of South Africa indicated that the number of initial public offerings (IPOs) on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) in the first quarter of 2015 accelerated to levels not seen since the global financial crisis, as the benchmark index rose to a record and companies took advantage of the rally – even as the broader economy is in the doldrums.

In 2014 there were two IPOs in the first quarter, in 2013 just one, and none in 2012.

It seems paradoxical that the stock market would be doing so well, considering the rest of the economy almost stagnating, with growth rates now less than 2% and unemployment almost 25%.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

While the rand has declined 2,4% against the dollar this year, the stock market has climbed 6,1% and touched a record in February; in effect, the JSE bears little resemblance to the economy.

But far from being an aberration, the disconnection between what happens on the JSE and in the wider South African economy is the key to understanding the country’s structural problems.

Mining is considered the backbone of South Africa’s economy, and historically, gold and diamond mines were central in making the country the richest on the African continent.

But today, the South African economy is actually driven by its financial sector, which, relative to the economy at large, is one of the largest in the world.

Data from the World Bank shows South Africa has the third-biggest market capitalisation relative to GDP in the world of 160%, second only to Hong Kong and Switzerland — small countries that are basically financial centres with little activity in other sectors.

Market capitalisation of the JSE – the share price of each company, multiplied by its number of shares on the exchange, and then added together for all the companies – is nearly three times as large as the country’s GDP.

It’s remarkable that a country of South Africa’s large size and population could have so much capital concentrated in its financial markets.

The reason for this is rooted in the apartheid era, where mining barons could not easily stash their profits outside the country, and so ended up accumulating it within the South African economy itself, and particularly in the stock markets.

Dutch disease of sorts

The effect is a Dutch disease of sorts, where money multiplies itself endlessly on the stock markets, therefore, there is little incentive to direct it into the productive economy – resulting in “jobless growth” and outsized gains for investors in the financial markets, who are able to comfortably live off interest accrued from their financial assets and do not necessarily have to build anything in the labour-absorbing economy in order to create wealth.

The gold and diamond mines reached their peak long ago, and most of them are now in decline. But the mining barons don’t really need today’s profits – which have dwindled anyway, exacerbated by the country’s expensive and sometimes fractious labour relations – they are living on profits generated in the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

The end of apartheid meant even better fortunes for the financial sector. Since 1994, South Africa’s already large and sophisticated financial services sector grew from 15,3% of GDP to 21,4% of GDP in 2009.

Apart from being over-financialised, which reduces the incentives to create “real jobs”, the other structural problem facing the South African economy is its over-formalisation.

The informal sector accounts for just 15% of South African jobs, compared to 70-80% in East Africa, for example.

The reason, again, hearkens back to the white-dominated economy that apartheid created, where the majority black population was only valuable for their labour, so any entrepreneurial self-sufficiency in the black community was stifled, in order to channel them into the wage economy.

When the ANC came to power, it did so with promises of redistribution and social justice, but big businesses won the day.

The ANC administration has largely been faithful to the inflation-targeting, economic liberalisation model, with a few (often politically-connected) blacks allocated rents in the form of the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) programme, but the overall structure has remained intact.

The over-formalisation presents a situation where a mama mboga (roadside vegetable seller) is expected to a get a food handling inspection licence, pay corporate tax, pay the official minimum wage and provide health insurance for her assistant before being allowed to open a (physical) shop.

Boda boda and okada

There is no space in such an economy for East Africa’s bodaboda or Nigerian okada (motorcycle “taxi”) riders or second-hand goods sellers, and so, no wriggle room to quickly accommodate the mostly black young people coming of age every year (the white population has a similar demographic profile to Western countries, and so does not have the pressure of a youth bulge; that bridge was crossed decades ago and easily dealt with by pro-white policies of apartheid).

Over-financialisation means there’s little pressure to create formal sector jobs, and over-formalisation means there’s little ability to create informal sector jobs.

It means that the ordinary black young person has very narrow options if they want to make a living; and lo and behold, in comes xenophobia and crime. And for political reasons, the ANC government can’t really be very hard on crime, in the style of Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni who, especially in his first 15 years in office, could do things like put a whole city on lockdown, flush out thugs and some would be shot, no apologies.

Those kind of things would remind South Africans of the apartheid regime, and would cost the ANC too much politically to be so heavy-handed “on their own people”.

Of course, there’s so much more to the whole story, including jealousy, ignorance, lack of skills and a sense of entitlement to goodies as part of the “fruits” of winning the struggle against apartheid.

But other times, you can find some of the answers in boring government economic data.—M&G