THERE is a book that has been sitting in my bookshelf for over a year.

Phillip Chidavaenzi

I just threw it in there after it was delivered by its author, Patrick Kandawasvika, on my doorstep.

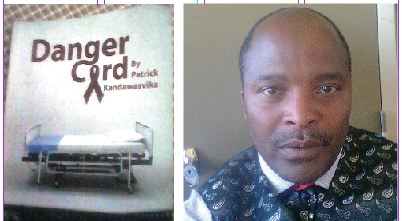

Although the book had an interesting title – The Danger Card – it took a long time for me to get to read it, but when I finally did last week, I found it quite intriguing in many respects.

Though written in the third person narrative form, The Danger Card (ISBN 9 781616 674571) story is told from the perspective of the protagonist, Stephen Gotora, as he lies dying of HIV–related illnesses after many years of a playboy lifestyle spanning several decades.

The story is told to an eager audience made up of fellow bed–ridden patients and the nurses attending to them. Written in a casual manner as if by a reluctant author, there are many moments of laughter in the narrative. But Kandawasvika’s subject is no laughing matter. HIV and Aids are serious matters!

I, however, commend the author for injecting huge dosages of humour to lighten up what could otherwise have been a grim tale. Stephen decides to break his silence and relate the colourful story of his life from the time he was fighting in Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle.

The story is punctuated by his mischievous adventures during his teenage years through his war experiences to casual escapades with sex workers in independent Zimbabwe.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

In a way, Kandawasvika allows his main character in The Danger Card, published in South Africa by Raider Publishing International in 2012, to share the narration of the story.

He uses HIV and Aids – regarded as a double-edged sword and death sentence in the 1980s before the advent of anti–retroviral therapy – to reflect the moral decadence characterised by corruption and immorality which were knocking on the country’s gates soon after independence:

“However, independence had brought with it corruption and immorality. Stephen had loathed the corruption and immorality that was rampant in the fledgling society… The rich continued to get richer while the poor got even poorer…” (pp31).

There is subtle irony in that while Stephen decries the widespread corruption in the new nation where females in need of employment had to offer sexual favours in exchange, he, at the same time, is also philandering with multiple sexual partners.

While one of the nurses who enjoy Stephen’s colourful tales, Eunice, is fascinated by the protagonist’s tales, she sometimes worries about her husband, Garikai, and often wonder if his eye ever strays to other women.

The author demonstrates how sexual networks have significantly contributed to the proliferation of the pandemic when it emerges that Garikai also used the services of sex workers housed at a lodge under the guise of a co-operative. What might be disturbing here is the revelation that some men may still seek the services of sex workers and still put up an effective camouflage.

The author writes: “Garikai, for all his other faults, always gave a good account of himself by performing his conjugal duties with an undying passion.” (pp36).

In a kind of getting–it–right–rather–too–late turn of events, Stephen eventually decides to settle down with one of the former sex workers, Gertrude, who can’t trace her background beyond herself because of unfortunate circumstances in her early childhood.

As the story pans out, however, it emerges that Stephen and Gertrude’s marriage is doomed right from the beginning as both are already infected with HIV. This is confirmed by the death of their child not long after it is born.

The book also delves into traditional perspectives to HIV and Aids with traditional healers associating it with witchcraft while others claim it infects women who would have had extra-marital affairs: “According to MaMoyo, the disease afflicting her grandson was caused by the fact that Gertrude had refused to own up and reveal extra-marital affairs she may have had during and after pregnancy” (pp65).

Kandawasvika takes us back to the onset of HIV and Aids in Zimbabwe when there was widespread stigma and discrimination that led to the ostracisation of people living with HIV.

Born in rural Wedza, Kandawasvika lives and works as a teacher in South Africa although he grew up in Harare. His debut novel is an interesting book that helps you look at HIV and Aids and issues surrounding the pandemic in an entirely different light.