THE British took control of the Cape of Good Hope in 1795, for eight years: a period known as the First British Occupation.

Travel with Dusty Miller

They returned in 1806 defeating the (Dutch) Batavian Republic at the Battle of Blaauwberg to usher in the Second British Occupation.

During British rule, ships were still being sunk and wrecked in Table Bay at an alarming rate. The first British effort to prevent this was the building of a stone pier at the bottom of Bree Street, which was completed but found almost useless.

A second stone pier was built at the site of Van Riebeeck’s jetty.

Ships could now load and unload cargo straight off the land without relying on cargo boats to go out to where they were anchored.

However, these piers proved inadequate as a defence against winter storms.

There was a safe, natural harbour in False Bay that was perfect for winter anchorage; discovered by Simon van der Stel in 1687 it became known as Simon’s Town.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

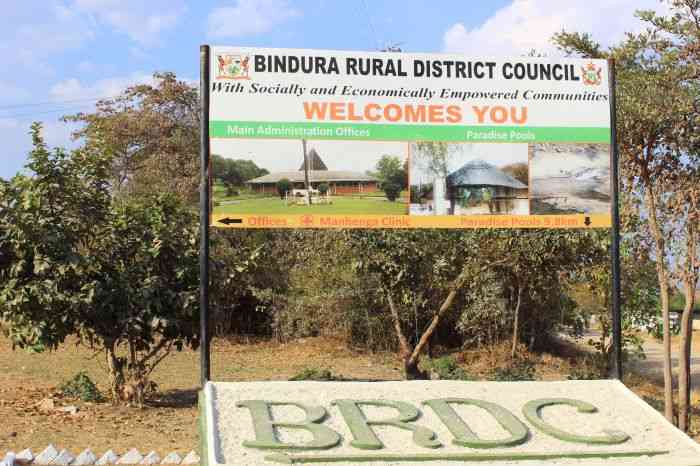

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The harbour there was developed by the British and used by the Royal Navy until as late as 1975 it is now HQ of the South African Navy.

It was never a suitable replacement for Table Bay as a civilian port, as there was only a narrow area between sea and mountains for the town to grow; Cape Town was too well established to be replaced and its distance from Table Bay in the 19th century meant a two-day trek by ox-waggon over difficult terrain.

With no satisfactory alternative as a safe, natural port, the authorities knew a man-made harbour must be built.

Cost was a major concern and politics played a part: other ports had been established up the east coast of southern Africa and were vying to be the preferred stopover on voyages to the Orient.

In 1856, Captain James Vetch, RN, drew up first plans for an enclosed harbour with an inner and outer basin, to be protected by two breakwater piers.

The following year a major storm hit Cape Town, sinking 16 large ships and seven smaller vessels.

Three days later the storm returned, taking two more large, expensive ships to the bottom of the bay.

Despite this, harbour work was still not started — the cost was thought to be prohibitive. The final decision to build a harbour was made following the news that insurance underwriters, Lloyds of London, would refuse to cover any ship anchoring at the Cape during winter, because of losses due to numerous wrecks.

Thomas Andrews submitted a modification of an earlier plan by John Goode, which was approved by Governor, Sir George Grey.

The design positioned the harbour to the right of Roggebaai, the normal place for shipping activities in those days, due to a need for a solid rock base from which a harbour could be cut, with the cut rock being used to create a breakwater.

On September 17, 1860, Prince Alfred, the 16-year-old son of Queen-Empress Victoria, pulled a silver trigger ceremonially releasing a truckload of rocks into the sea, to start construction.

More than 20 000 people turned out near the present site of the Chavonnes Battery to witness the historic event. Among them were the Xhosa chief, Sandile, and Soga, the first black Presbyterian minister in South Africa.

Prince Alfred returned later to officiate at the opening of the Alfred Basin, followed by another trip to lay the foundation stone for the Robinson Dry Dock.

This potted history of the Victoria and Alfred harbour wouldn’t be complete without the story of the people who built it with blood, sweat and tears.

The authorities realised it would be too expensive to hire building workers, so they turned to convict labour. The first prisoners were housed in the Chavonnes Battery.

When half the battery was demolished to make way for the basin, they were moved to the newly-built Breakwater Prison (present site of Breakwater Lodge Hotel). By 1885, there were 2 360 convicts working on the basin and breakwaters.

It was said Breakwater Prison was one of the most feared in the world, along with Dartmoor, at Princetown in Devon, UK and Devil’s Island off French Guiana in South America and that there was at least one representative of each race or nationality in the known world incarcerated there.

Segregation of races was not an issue at first; indeed the sleeping arrangements were that a white prisoner had to sleep between two black convicts in the belief that with language and cultural barriers there would be less plotting and dissent. (It didn’t work!)

One of the largest groups within the prison consisted of those convicted of illicit diamond buying (IDB) on the Kimberley Diggings.

They were not hardened criminals, but an uncut diamond found in a pocket meant five to 10 years at the Breakwater.

Progress on the 1 430m long breakwater depended largely on the rate of conviction of IDBs.