THE Community Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (Campfire) is premised on the conservation of wildlife and other natural resources as a livelihood option for rural communities in marginal areas of Zimbabwe.

Charles Jonga

Some 58 out of 60 districts in the country are members of the programme, although just 16 of these are regarded as “major” Campfire areas in which income generation is primarily through big-game trophy hunting.

The Campfire Association provides interface with districts to enhance training and capacity for data collection and community awareness on protocols for problem animal management and anti-poaching.

As the forerunner of Community-Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM), Campfire has significantly influenced and contributed to similar models throughout southern Africa where CBNRM is now generally accepted and practised.

At international level, Campfire has been influential in supporting the rights of local people to manage and benefit from their own natural resources, and in developing an understanding of sustainable wildlife utilisation and common property management.

This is testimony to the efficacy of the principles upon which the programme is based.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The United States Agency for International Development (UsAid) was a major funder of Campfire from 1989 under the Natural Resources Management Project (NRMP I). Initial support targeted four districts — Tsholotsho, Hwange, Bulilima, Mangwe and Binga.

Wildlife management activities by the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority were also supported in the Hwange-Matetsi complex.

The successor Usaid funded programme (NRMP II) extended support beyond the limited number of districts and embraced Campfire in its totality from 1995-2003.

Currently, Campfire generates on average $2 million in net income every year which is much lower than estimated potential earnings for the programme.

Income generation is mostly through the lease of sport-hunting rights to commercial safari operators, as well as sales of hides and ivory, tourism leases on communal land and other natural resources management activities.

As an industry, safari hunting has proved to be robust both environmentally and economically and, although not unscathed, has also proved fairly resilient in the face of serious socio-political uncertainty.

Potential earnings for communities could be multiplied many times over through more efficient management and regulation of CBNRM enterprises and, most importantly, through direct participation of communities in all levels of the value chain.

There are over 200 000 households that actively participate in Campfire hunting areas. Revenue received by communities, though relatively small, is used to directly offset the costs of living with wildlife through employment of game scouts or resource monitors.

Rural communities under Campfire, derive their livelihoods from subsistence farming of drought resistant crops. The main crops produced are sorghum, maize, pearl millet, cowpeas, and other cash crops.

Environmental changes are negatively impacting on farming in these areas as the fertility of the land is gradually decreasing, affecting both the quality and quantity of harvests and impacting negatively on food security.

Livelihoods of these communities are complemented by the revenue generated from the sustainable utilisation of natural resources, especially trophy hunting of elephant. In addition to climate factors, the abundant and thriving population of elephants has greatly contributed to very poor agricultural output with most fields totally destroyed every cropping season. Disgruntled communities easily become willing tools for sophisticated wildlife poaching syndicates.

An analysis of data presented in October 2013 as part of an Economic Valuation, Ecosystem Based Adaptation and Resilience and Biodiversity Mainstreaming for the Revision of the Zimbabwe National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) by Anne Madzara provides an estimated total of $2 496 349 from hunting in 2012.

Hunting contributes an average of 90% of Campfire revenue annually. Five out of 13 districts contributed 84% of the hunting revenue. This shows the extent of variability between districts.

An assessment of 18 main Campfire districts allocated hunting quotas for 2014 shows that 106 out of 167 Bull Elephant hunts were booked by US citizens. Elephant trophy hunting contributes more than 70% income to the Campfire programme.

2014 Trophy — elephant hunt bookings in campfire areas

Photographic tourism revenue Photographic tourism contributes an estimated 1,8% of total Campfire revenue annually according to 2006 evaluation reports on Campfire.

Campfire invested significantly towards the development of Photographic Tourism in communal areas through the USaid between 1999-2003.

There are a total of 21 facilities which are managed either in partnership with private sector (five facilities) or by Community Trusts (16 facilities).

Private sector players operate these ventures under tripartite lease agreements with RDCs and communities who are the major beneficiaries. Current revenue data from the 21 photographic tourism facilities is not available, as activity in these camps has been low over the last 10 years.

Due to lack of investment, most of the facilities are semi functional.

Revenue from other sources

Other revenue sources to Campfire include fisheries, sand and quarry extraction, harvesting of Ilala and Masawu (wild fruit), beekeeping, sale of ivory and hides and logging of indigenous timber.

Other income sources combined with ecotourism contribute about 10%. In 2012, four districts in the Lower Zambezi area initiated REDD+ projects in partnership with the private sector. Value of Campfire ivory stockpile

Due to the Cites controls in trade in elephant and its specimens, all ivory from Campfire districts, forestry and parks estate is stockpiled at Zimparks stores.

Of the current stock that the Parks stores holds, about 16% belongs to Campfire communities. The current value of the Campfire ivory stockpile is estimated at $2,5 million.

Gross revenue from Campfire areas According to the Community Based Natural Resource Management Stocktaking Assessment Report by Mazambani and Dembetembe (2010), 45% of the gross hunting revenue goes to the Campfire while 55% goes to safari operators (Box 3). According to the same report, key stakeholders including safari operators realised a cumulative $89 million between 1989 and 2006.

The multiplier effect of Campfire ecosystems goods and services Campfire is widely acknowledged for its positive impact on rural livelihoods and the rural economy at large. Campfire has stimulated the rural economy in the following ways:

lIn 2007 it was estimated that 777 000 households from 37 districts benefited from Campfire directly or indirectly. Given that 58 districts now participate in Campfire, it can be estimated that the number of direct and indirect beneficiaries exceeds 1 million.

lFrost and Bond (2008) estimate that about 12 districts out of the total participating districts have prime wildlife areas, covering 118 wards and benefiting approximately 121 550 households.

lIn 2012 the revenue distributed directly to producer communities from 13 districts is estimated at $1,4million. This reflects the amount of money injected into the rural economy.

lData from 1994 to date (excluding 2007 and 2008) shows that Campfire accrued cumulative revenue of $39million. Using the current revenue allocation system the amount accruing to the community wildlife producers is $21,5million.

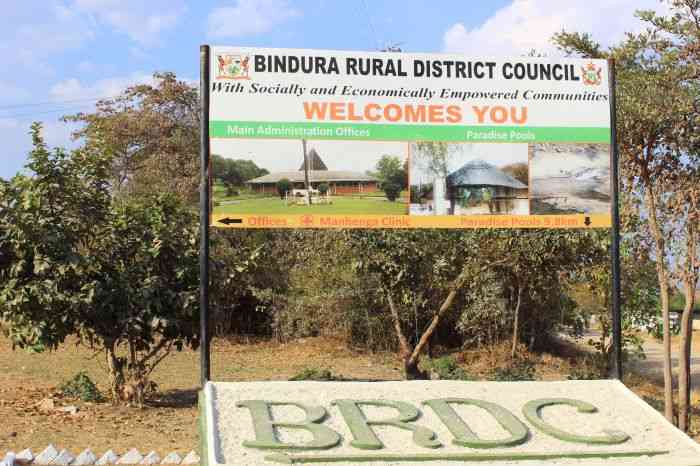

lNearly 50 hunting concessions have been parcelled out by 28 Campfire hunting districts, and a total of 33 outfitters are contracted by RDCs to provide safari hunting services. The outfitters employ locals to provide hunting support services.

Use of Campfire income: Community projects

In all Campfire districts, revenue from hunting is used to support various management activities such as; fire awareness and purchase of fire-fighting equipment; opening of roads and fireguards; training of committees; look and learn tours to other Campfire districts; purchase of communication equipment; purchase of firearms for Resource Monitors; and rehabilitation of water supply systems to hunting areas. Campfire thus contributes to job creation, empowerment, and diversification of livelihoods for rural communities. Substantial investments are also made annually by RDCs and safari operators in problem animal control (PAC) and anti-poaching.

Most of the income has been invested in infrastructure which has long term benefits to local communities. Infrastructure such as clinics, schools, and grinding mills, boreholes, roads, fencing to keep out wildlife, has been set up in a number of districts (Table 10). Purchase of tractors and drought relief food by communities has also contributed to food security in many drought prone Campfire areas. Children benefit from reduced walking distances through the construction of schools in the wards.

Others benefit through procurement of learning materials and payment of school fees from Campfire proceeds. Communities also benefit from meat from safari hunting operations and occasionally from problem animal control.

Employment The Campfire programme contributes to employment at local level. At district level, Campfire managers and officers, timber measurers, office clerks, and game scouts, while community projects employ resource monitors, tour guides, preschool teachers, grain millers, and bookkeepers are employed.

A growing number of ordinary community members are also self-employed to service various Campfire activities. Safari operators employ managers, scouts, trackers, professional hunters, bookkeepers, drivers, cooks and camp minders.

A detailed survey of 16 districts shows that Campfire employs a total of 256 resource monitors/game scouts. In addition to this, RDCs employ Campfire coordinators who are supported by administration clerks.

In 2013, Mbire District employed, 70 resource monitors, 80 people in fishing camps, and 100 people in hunting camps. An assessment of five districts in 2009 revealed that Campfire was 62% understaffed.

The potential for increased impact of Campfire through employment is therefore high.

Arguably, although perhaps still falling short of their true potential, Campfire areas such as Mahenye in Chipinge, and Masoka in Mbire, for example, in which communities and community leadership have retained central involvement, promoted community awareness and played strong, proactive roles in Campfire, those areas have performed decidedly better — both from the point of view of community participation, benefit and development as well as from the point of view of contribution to conservation and protection of wildlife and other Natural Resources.

Campfire values sustainable good quality trophy hunting has supported regular training of game scouts and community awareness on wildlife management.

The loss of this income stream will certainly increase the loss of confidence by communities in wildlife management, and consequently threaten tolerance and survival of the elephant. Community antipathy to wildlife and the reciprocal costs to wildlife is set to increase, especially through retaliatory killing or self-help problem animal control (PAC), and commercial poaching to feed international syndicates.

Communities are disillusioned with the suspension of elephant trophy imports into the US, and are more likely than ever before to succumb to the temptation to open up more land for rain-fed agriculture in areas generally unsuitable for cropping leading to massive land degradation.

The disruption of hunting revenue inflows and investment into the protection of wildlife and direct incentives at community level is a sure way to increase elephant poaching and human encroachment into wildlife areas.

Human and elephant conflict in wildlife areas

There is generally no fencing separating wildlife from people, as villages share close boundaries with wildlife areas, with some settlements located in close proximity to State protected areas.

This results in the sharing of water and grazing between people and elephants.

Conflict with elephant is most intense when elephants raid field crops, stored harvests and property during the night. In most cases, villagers end up harvesting immature crops, which reduces both crop yield and value.

During winter months, surface water supplies dwindle resulting in other forms of conflict such as destruction of water sources and installations, threat and loss of human life, and vegetation destruction.

Not all incidents of problem animals are reported, as Campfire staff generally lack the capacity to attend to every report on time. In addition, there are restrictions of people’s movements, and their access to essential commodities such as firewood. On average communal farmers in the buffer area spend about two months per year guarding their staple crops from wildlife.

Guarding is mostly done at night, and costs farmers untold hardships, additional expenses, and even injury and death. Campfire communities have developed their own locally acceptable compensation mechanisms, such as full support towards burial expenses in cases of loss of life, and education for school going orphans.