By Ibbo Mandaza

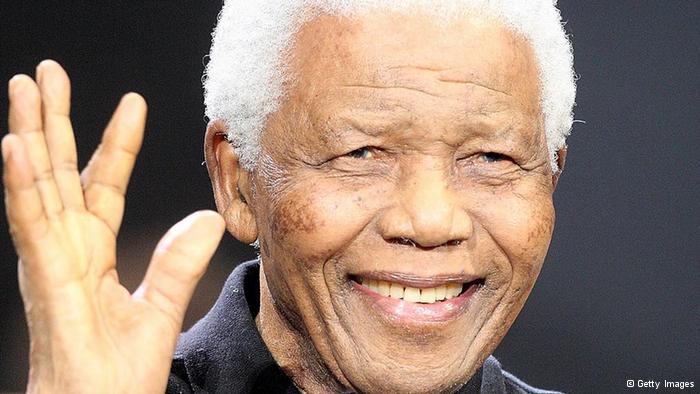

However, the only difference, perhaps, between Mandela the African nationalist and those of his contemporaries (including our own President Robert Mugabe) is that the latter stayed too long on the throne to see their hands soiled in the muck and mud of post-independence failure, economic malaise and the consequent erosion of the democratic ideals for which most of these African nationalist leaders were prepared to sacrifice so much and, in his own words at the Rivonia trial in 1964, “for which I am prepared to die”.

In retrospect, Mandela will have savoured his decision in 1999 to call it quits after only one term of office as the first President of a free and independent South Africa: in 2008, he expressed immense disappointment at the “tragic failure of leadership” in Zimbabwe; and witnessed in his retirement the emergence of similar problems in his own South Africa, including the xenophobic violence against fellow Africans in 2008, not to mention the mowing down of 44 miners in Marikana in 2012.

So, here are the hallmarks of African nationalism of which Mandela was its most poignant expression and legacy: selfless sacrifice in the pursuit of liberation; reconciliation and forgiveness in victory; and, as I will illustrate shortly, an incorrigible commitment to a liberal/capitalist ideology, which has ensured continuity rather than transformation of the colonial-type extractive economic system in post-independent Africa.

Indeed, African nationalist ideology is founded essentially on two inter-related neo-liberal themes. First, an implicit faith in Western values, institutional arrangements and related paraphernalia (including cultural, ceremonial and even garb). The (bourgeois) state model which the African nationalists inherit with political independence epitomises as much this faith as the exercise of power and privilege that is on hand for the new class of rulers.

So, whether it is Nelson Mandela in No Easy Walk to Freedom or Ndabaningi Sithole in Africa Nationalism, the Western value system is taken for granted, as an integral part of any dispensation that the African nationalists could one day wish to see established in their countries.

Often forgotten, therefore, is the extent to which African nationalist leaders like Mandela himself, Kenneth Kaunda or Mugabe, are so much creatures of a colonial system that has left an indelible mark on their thought processes, their lives and their aspirations.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Less obvious initially, but increasingly problematic with the passage of time into post-independence, is the extent to which the political and socio-economic terrain inherited as part of the dispensation has not been favourable to the development of such institutions – eg parliamentary democracy, separation of powers independence of the judiciary, accountable executive, etc – that underpin the conventional bourgeois value system.

Sadly, it is in the economic sphere that the African nationalist agenda has fallen short of the expectations of its vision of freedom and prosperity for all: unlike the bourgeois state after which model it is in pursuit, the African nation-state-in-the-making lacks the economic foundations – and the anchor (or national bourgeoisie) in particular – through which to inherit a commendable level of national confidence, project national interest, and create a national economy. Hence the sustained hegemony of parasitic and comprador classes most of whose members have grown paripassu this post-colonial pathology, and largely dependent upon the state, internationalised capital or an institutional aid regime.

For, as has already been intimated, it has been the curse of continuity rather than change, especially in the economic field wherein the African nationalist were least equipped in terms of technical capacity and experience.

The leadership in particular had little appreciation of the workings of an economy in which Africans had been largely labourers and pre-empted from managerial and leadership positions. Most African leaders completely underestimated the central importance of the economy in favour of a pre-occupation with the “political kingdom” – and with such disastrous consequences as we see today, not least in Zimbabwe right now.

This is why the occasion of Mandela’s departure prompts more a swan song of yesterday’s African Nationalism than hopeful expectations for a better economic tomorrow.

Hence, the emphasis on the second theme of the African nationalist ideology for which Nelson Mandela will most be remembered: the vision of a democratic society in which the violations and denials of the colonial era would be a thing of the past, and a new meritocracy established.

As has already been stated, it was a vision for which many an African nationalist were prepared to die; it is that selflessness that is almost unique to African nationalism itself.

But this is also bundled together with the forgiveness and reconciliation that is also so rare if not unique to the Southern African brand of African nationalism: borne out of the peculiarities of white settler colonialism and the necessity for compromise and reconciliation as the basis for transition, but an almost endless one apparently,from white minority rule to national independence.

Even those of us who witnessed the intricacies and complexities of the transition from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe in the 1980s – or from apartheid South Africa to freedom and independence in the 1990s – sometimes forget, expediently or otherwise, those historical circumstances that lend themselves to compromises that might today appear, to the “born frees” in general, nothing less than a “sell-out”.

Needless to add, without forgiveness and reconciliation, particularly in South Africa, the alternative outcome might have been too ghastly to contemplate.

Yet, many an observer of the South African situation has been somewhat startled at the apparent unbridled levels of forgiveness and reconciliation on the part of Mandela in particular, but lest we forget the 1980s, also Mugabe, before the events of the 2000 referendum provoked the onslaught on the white farmers who had been the main beneficiaries of more than 20 years of post-independence reconciliation.

Thus, even conservative Ali Mazrui remarked in 1998:

“Cultures vary considerably in their hate-retention. The Irish have high retention of memories of atrocities by the English. The Americans have long memories of atrocities committed against them by the Turks in the Ottoman Empire. The Jews have long memories about martyrdom in history. On the other hand, Jomo Kenyatta proceeded to forgive his British tormentors very fast after being released from unjust imprisonment. He even published a book entitled,Suffering with Bitterness. Where but in Africa could somebody line Ian Smith, who had unleashed a war which killed thousands of black people, remain free after black majority rule to torment his black successors in power whose policies had killed far fewer people than Ian Smith’s policies had done? Nelson Mandela lost twenty-seven years of the best years of his life. Yet on being released he was not only in favour of reconciliation between blacks and whites. He went to beg white terrorists who were fasting unto death not to do so. He went out of his way to go and pay his respects to Mrs Verwoerd, the widow of the architect of apartheid. Is Africa’s memory of hate sometimes “too short?”

In the final analysis, it is this fountain of forgiveness and reconciliation – the indispensable components of African nationalism, especially in Southern Africa – that has earned Nelson Mandela universal affection, not least among white South Africans most of whom had been socialised and educated to believe that liberation would be synonymous with black rage and revenge, almost naturally, for centuries of white colonialism, economic exploitation, violent oppression, destitution and wanton killings.

So, it is, too, that Mandela the African nationalist has been the mirror which centuries of racism – a singularly Caucasian-based disease, born and bred in the context of Europe’s rape and scourge of Africa and its people since the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – can look at itself in guilt, embarrassment and shame, at having de-humanized another section of humanity.

So, if Nelson Mandela is the international icon – the symbol of universal humanity – it is also because even those who yesterday flirted with apartheid can now salvage their consciences by extolling Mandela today, hopefully kicking themselves for having been so blind to the inexorable march of history, the liberation of the African person, the recovery of African dignity.

And yet, herein lies the paradox of history: an African nationalism borne out of the indignities of racism and racial oppression and exploitation; a product of European colonialism and its Christian religion and education; the inheritor of the colonial state and all its paraphernalia but without the requisite economic capacity for transformation; and, above all, a Nelson Mandela, the ultimate African nationalist.

Ibbo Mandaza is a Zimbabwean academic, author and publisher; he is currently convenor of the Policy Dialogue Forum, Sapes Trust, a regional Think Tank headquartered in Harare. Email: [email protected]