THE Shona adage chinokanganwa idemo when loosely translated means what forgets is the axe, not the tree that was cut down.

REPORT BY TAPIWA ZIVIRA, ONLINE REPORTER

The saying aptly captures the situation victims of Operation Murambatsvina are going through, as this month marks eight years after government embarked on a drive to forcibly clear slums in urban areas.

“While the bulldozer destroyed our house, my little daughter asked a question that still haunts me; ‘Torara pai imba zvayapazwa?’ (Where will we sleep as our house has been destroyed?)” This is the story of a bitter 42-year-old Maxwell Maramba* of Whitecliff.

May of 2005, Maramba and other Zimbabweans woke up to the news that government was to embark on a massive clean-up exercise — Operation Murambatsvina — to “sanitise” urban areas.

President Robert Mugabe said the operation was required “to restore sanity” and that it was an “urban renewal campaign”.

Local Government minister Ignatius Chombo, whose ministry was at that time responsible for housing, said: “It is these people (illegal settlers) who have been making the country ungovernable by their criminal activities.”

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

But Maramba was confident the blitz would not affect him.

“I was paying official subscriptions to a housing co-operative that had facilitated the stand on which I was building my house, so I was sure we were legal,” he said.

As a security guard, he used his wages to subscribe to the housing co-op, and the remainder for the construction of a seven-roomed house.

Unknown to him, horror was on its way as undeterred city council officials armed with demolition tools and bulldozers, all guarded by police, descended on his area on one cold June afternoon.

“Within a few hours, hundreds of houses had been reduced to piles of rubble, with the sorry sight of victims standing helplessly by their belongings

Maramba’s family and several others were not fortunate enough to be moved to the transit camps set up in farms near Harare.

“My family and I put up under that tree for six months until we rebuilt the shack that we now live in,” he said, pointing to a msasa tree next to his shack, “I am still too bitter to forget about the incident.”

By the end of July 2005 thousands of houses, vending stalls and small industrial stalls deemed to be illegal, had been destroyed under the infamous Operation Murambatsvina and truckloads of people being ferried to the newly-established transit camps became a daily sight in most urban areas.

The operation drew international attention and a high level United Nations delegation came to assess the situation and reported that about 2,4 million Zimbabweans had been affected by the operation.

Faced with criticism, government — with the help of some humanitarian organisations — embarked on a corrective operation termed “Garikai/ Hlalani Kuhle”.

Garikai was put in place with the idea that government was to provide plots where people could build their own homes while a few vulnerable would get assistance with housing. Whitecliff, Caledonia and Hopley where thus earmarked for the programme.

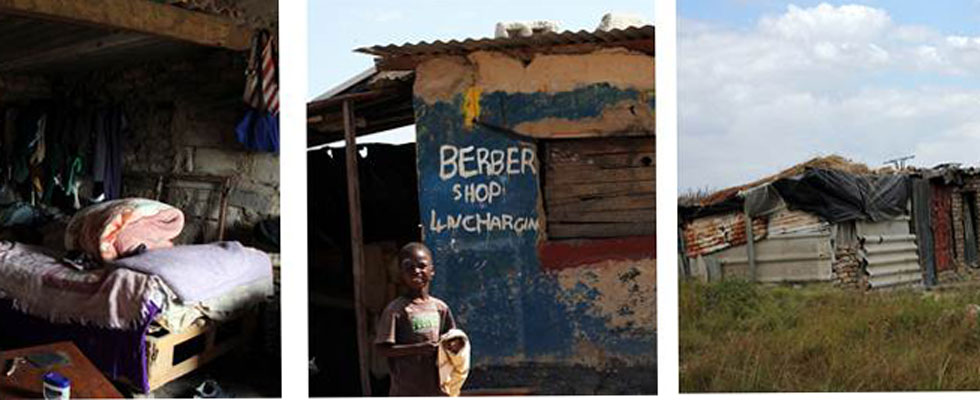

But if the living standards at Hopley and Whitecliff — as recently witnessed by a NewsDay crew — are to be the yardstick of government’s makeover to Murambatsvina victims, then Garikai certainly fell far short.

Most Hopley residents live in plastic or wood shacks. Others live in partially finished brick and mortar houses with no doors, windows, or proper roofs.

A report of the portfolio committee on Local Government on progress made on the Operation Garikai /Hlalani Kuhle Programme by June 2006 concluded that “the erratic disbursement of allocated funds contributed to the failure by the ministry to meet its targets in the construction of housing units, vendor marts and factory shells”.

Since there is no running water and electricity, the daily grind for most residents is the scramble for water sources and the search for firewood.

“There are few people who have built safe wells at their homes so we have to battle it out to get water from the few alternative sources before the water runs dry,” said one woman who identified herself as Amai Blessed.

Some travel to neighbouring farms to search for firewood, but they risk getting arrested and fined for trespassing.

As the country’s economy remains in trouble, most people who live in Hopley have no formal employment, making the place a hub of criminal activities and illegal beer brewing.

Young girls are forced into prostitution. An 18-year-old girl, Chipo* looks after her octogenarian grandmother and little sister after her parents passed away two years ago.

Her challenges started in 2005 when she was forced to drop out of school as her parents’ small business in Mbare was destroyed under Murambatsvina.

“My parents came to settle here and since they had no source of income, I could not keep going to school,” she said, “It was never my choice to get into sex work, but as hardships mounted after my parents died, I was left with no choice as my grandmother and little sister all looked up to me for everything.”

With no secondary school nearby, pupils have to endure a journey to Highfield, Glen Norah or Waterfalls all more than five kilometres away.

The UN reported out that about 220 000 children of school-going age were directly affected by Murambatsvina.

Pregnant mothers bear the brunt of walking to the nearest Rutsanana Maternity Clinic – about 7 kilometres away — for the vital maternal health services.

“Many women are forced to give birth at home in unhealthy conditions, without skilled midwives, risking the lives of their new-born babies and the mothers,” said Caroline Zvaita, whose baby died during the transit period to Hopley in 2005.

“Our house was destroyed when I was almost due for birth and I had to give birth in a moving truck while we were being transported to this place. My baby died a few hours after birth,” she said.

Eight years on, the marks of the Operation Murambatsvina axe are still visible at Hopley, Whitecliff and Caledonia as government fails to provide proper accommodation.

Names have been changed to protect the identity of the interviewees